Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, and David Glasgow Farragut followed a remarkably similar path to Civil War glory.

All three were little more than fringe players in the Union military in the early stages of the war: Grant merely the captain of a company of volunteers in his hometown of Galena, Illinois; Sherman the head of a streetcar company in St. Louis; and until December 1861 Farragut had to settle for being only a member of the Naval Retirement Board in New York.

Within a year, all three had become household names across the North.

By 1865 all three had attained military immortality.

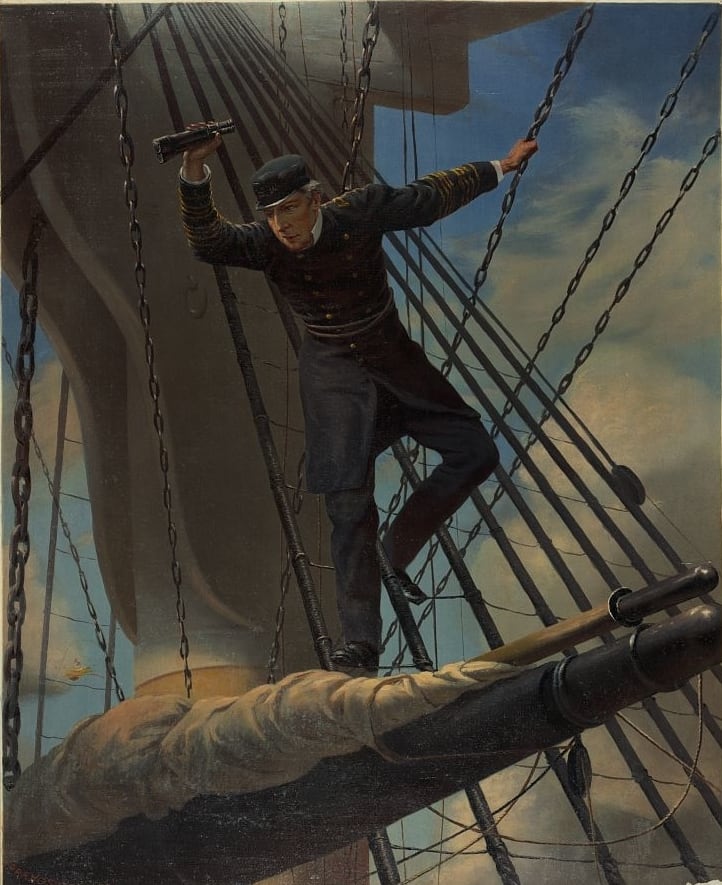

Of the trio, Farragut’s accomplishments were in some ways the most unfathomable and yet singularly spectacular.

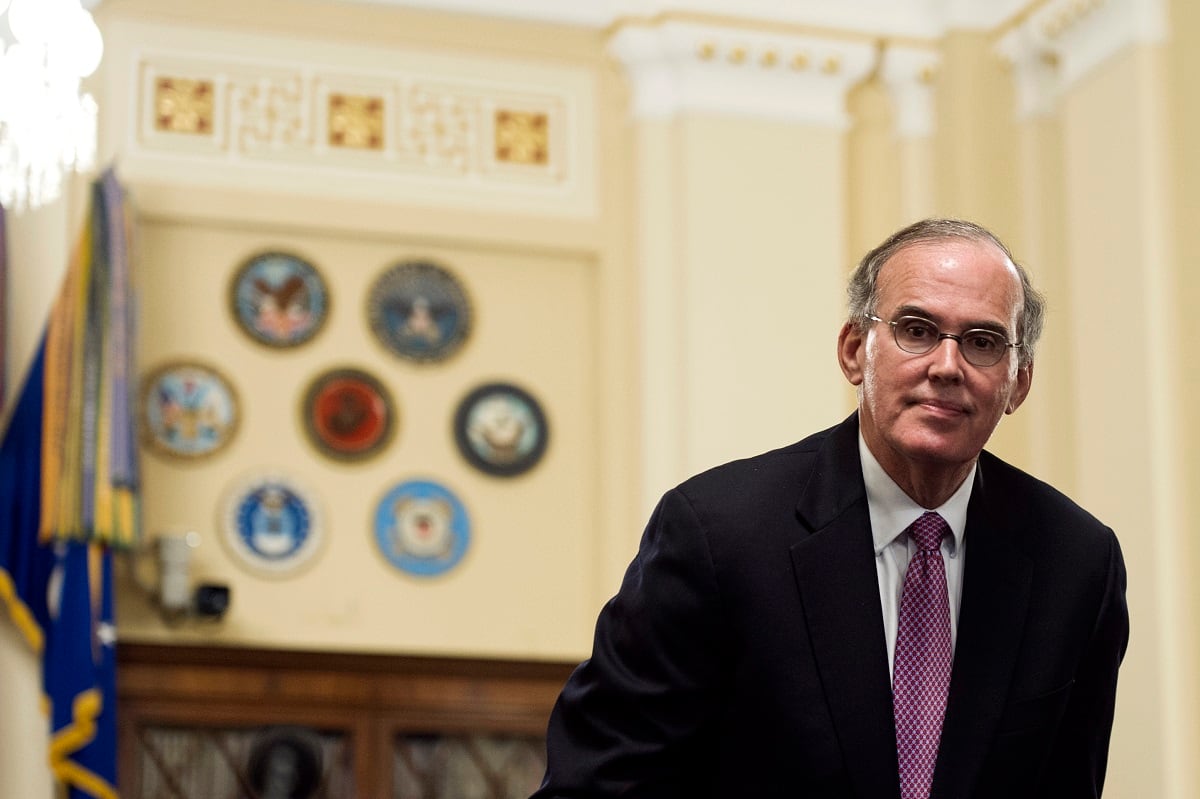

Nearly 60, he was in the twilight of his career when the war began, having already spent 50 years in the U.S. Navy.

Though a Southerner by birth and a longtime resident of Norfolk, Virginia, with a Southern wife, he chose the Union over the Confederacy.

On April 18, 1861, the day after Virginia formally seceded, he departed Norfolk with his family and settled in Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y. It was by no means an easy decision. Farragut made no secret he believed secession was treason, but he also feared he’d be ordered to defend Norfolk’s Naval Yard against his relatives, friends, and neighbors if he stayed there.

Some officials in Washington, D.C., remained dubious of his loyalties, hence the unglamorous assignment to the Naval Retirement Board.

But Farragut’s fortunes finally changed in December when the Union high command decided to attempt the capture of New Orleans — the South’s largest city and most important port — by sea rather than land.

Farragut was the best available officer and had the characteristics necessary to command the naval contingent of the expedition. U.S. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles plucked him from his desk job and in January 1862 gave him command of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron.

Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus V. Fox, in particular, paid tribute to Farragut for deciding to leave Norfolk back in April, declaring it was an act that showed “great superiority of character, clear perception of duty, and firm resolution in the performance of it.”

Farragut quickly proved that the gamble on him was well worth taking.

During his half-century in the Navy — appointed a midshipman as a 9-year-old, he first went to sea at the tender age of 10 — Farragut was regarded for his dependable, if understated, service.

Until his command of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, however, there had been little indication he’d have a chance to secure his name in history. Born James Glasgow Farragut on July 5, 1801, at Campbell’s Station (now Farragut), Tennessee, he was the second son and second of five children.

His Spanish father, Jordi Farragut Mesquida, took the American name George and was a sea captain before joining the colonists in their revolt against Great Britain. Glasgow’s mother, Elizabeth, was of Scots-Irish descent.

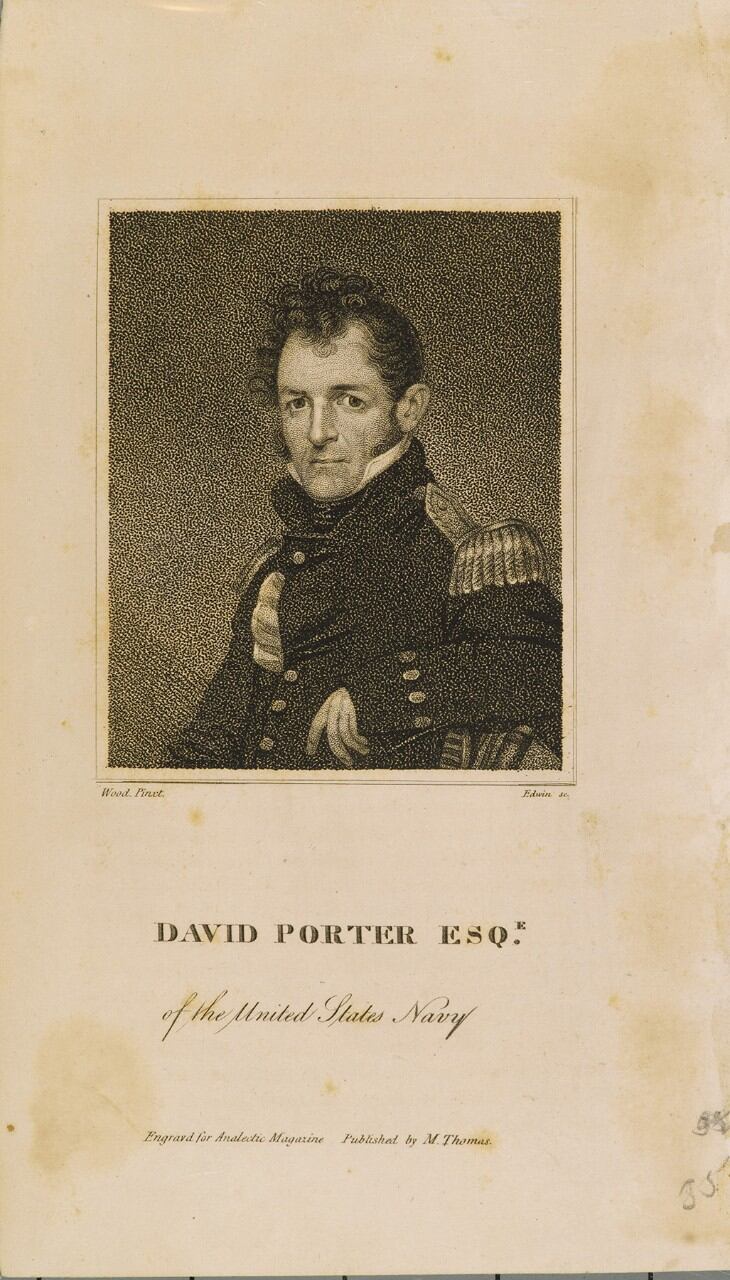

In 1807, the Farraguts left the Tennessee wilderness behind and moved to New Orleans, where George became a sailing master at the American Naval Station and close friends with fellow sailing master David Porter Sr., grandfather of David Dixon Porter, a future Civil War admiral.

When Porter, a Revolutionary War veteran weakened by tuberculosis, suffered sunstroke, Elizabeth Farragut nursed him, though she was sick from yellow fever herself.

They both died on June 22, 1808.

During his father’s illness, David Porter Jr. assumed command of the naval station. Grateful to the Farraguts, he helped make retirement arrangements for George on a plantation on the Pascagoula River in Spanish West Florida. And on Dec. 17, 1810, he secured for Glasgow — as James Farragut preferred to be called — an appointment as a midshipman in the U.S. Navy, the third-youngest individual ever to receive such a commission.

In honor of the occasion, Porter gave the 9-year-old a gold watch inscribed “D.P. to D.G.F., U.S.N., 1810” — the earliest reference to Glasgow’s first name being changed from James to David. (Naval records indicate, however, that Glasgow did not authorize the change until after his father’s death in 1817.)

After attending school in Washington as well as the naval shipyard at Chester, Pennsylvania, Farragut departed with Master-Commandant David Porter Jr. for Norfolk in July 1811. The 10-year-old was going to sea — the youngest officer ever to serve on active duty in the U.S. Navy.

On Aug. 9, Farragut received his first command, the wherry that transported Porter to and from the frigate Essex; his crew consisted of one seaman to work the oars. Though probably less than 5 feet tall wearing shoes, “Mister Farragut” had spunk. When the “miniature” officer was mocked in Norfolk one day, a brawl ensued. Farragut pulled his dirk and entered the fray. He and his victorious mates landed in jail, but Porter bailed them out. Young Farragut, he observed, consisted of “three pounds of uniform and seventy pounds of fight.”

During the War of 1812, Farragut accompanied Porter during a lengthy and particularly memorable cruise. While sailing along the coast of South America in January 1813, Porter elected to violate his orders and sail for the Pacific Ocean, a bold move for a single vessel during wartime.

Essex embarked on a 2,500-mile trip to Cape Horn, at the southern tip of Chile, but the ship nearly sank in a storm on March 3. Injured, Porter was confined to bed, and Farragut, for the first and only time in his life, witnessed sailors paralyzed with fear while battling Cape Horn’s raging seas.

In rounding the Horn successfully, however, Essex became the first American warship ever to enter the Pacific. Despite the threat of British warships stationed nearby, Porter gambled and anchored at Valparaiso, Chile. After what they had been through, he reasoned, the crew deserved shore leave.

By the end of June, Porter had captured nine enemy prize vessels, and Farragut was placed in command of one of those — Alexander Barclay — five days before his 12th birthday, When the British vessel’s prisoner-captain threatened to regain control, Farragut promised that if the captain set foot on the deck brandishing pistols, he would be thrown overboard.

There was no further trouble. Farragut rejoined Porter on Sept. 30.

On Oct. 25, 1813, Essex dropped anchor off Nuku Hiva, a tropical island paradise. Though he had deemed an 11-year-old Farragut capable of commanding a vessel, Porter at first kept the midshipman, now 12, from interacting with the island people, but he later relaxed the constraint, as the ship was at anchor for a lengthy period.

Farragutt later described learning to throw a spear, walk on stilts, and improve his swimming technique.

In February 1814, Porter gave his young apprentice a lesson in risk-taking that, as Civil War events would show, had an impact on Farragut.

It involved a conflagration between Essex and another of Porter’s ships and two British vessels in the neutral harbor of Valparaiso. Porter’s ships were woefully outgunned, and when he decided to run past the enemy duo — fearing the arrival of other British ships — a squall nearly capsized Essex near the mouth of the harbor.

Several sailors were drowned, and the ship lost its main topmast.

Now disabled, Essex laid anchor, only to be attacked. Porter and Farragut were both injured but remained at their posts, with the midshipman losing his coattails while trying unsuccessfully to prevent the quartermaster from being struck by a projectile.

Unable to run his vessel ashore, Porter finally ordered “abandon ship” and then struck the colors.

Thus ended what would prove to be the bloodiest contest involving a single American ship in Farragut’s career. Of Essex’s complement of 255 men, 58 had been killed or mortally wounded, 39 severely wounded, 27 slightly wounded, and 31 were missing.

Years later Farragut severely criticized Porter’s tactics at Valparaiso, but, significantly, he never condemned his mentor’s questionable strategy.

Between 1815 and 1820, Farragut sailed primarily in the Mediterranean. Still a midshipman, he availed himself of every educational opportunity, and finally returned home to take the examination required for a lieutenant’s commission.

Though probably the most professionally knowledgeable midshipman of his era — maybe of all time — Farragut failed the exam, likely because he had run afoul of a naval clique dominated by Capt. George W. Rodgers and the illustrious family of Capt. Oliver Hazard Perry.

The three-man examining board gave no official reason for failing Farragut, so the Secretary of the Navy allowed him to try again before the next board.

In October 1821, Farragut passed. Then in September 1824, after spending time chasing pirates in the West Indies and receiving his first regular command, the Ferret, he married Susan C. Marchant of Norfolk. Shortly after the wedding, Susan contracted a neuralgia that afflicted her until her death in 1840.

On Dec. 26, 1843, the widower married another Norfolk resident, Virginia Loyall. She was the mother of his only child — a son, Loyall, born Oct. 12, 1844.

Despite his lengthy service and evident ability, promotion came slowly for Farragut, though his desire to care personally for his sickly first wife may well have played a part in that. In addition, Farragut’s level of seniority did not entitle him to one of the limited number of commands available before 1861.

Promoted to first lieutenant in January 1825, Farragut saw limited duty but did at least have a few interesting moments: transporting Revolutionary War hero the Marquis de Lafayette to France in 1825; showing the flag at Charleston, South Carolina, during the Nullification Crisis of 1833; and witnessing the naval reduction by the French of Castle San Juan de Ullua at Vera Cruz, Mexico, in 1838.

Promoted to commander on Sept. 9, 1841, Farragut sought action in the Mexican War but had no opportunity to distinguish himself. He would receive his captaincy on September 14, 1855, and served in California until 1860 before returning to Norfolk.

Farragut’s area of responsibility with the West Gulf Blockading Squadron stretched from St. Andrew’s Bay, Florida, to Texas and south to the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico.

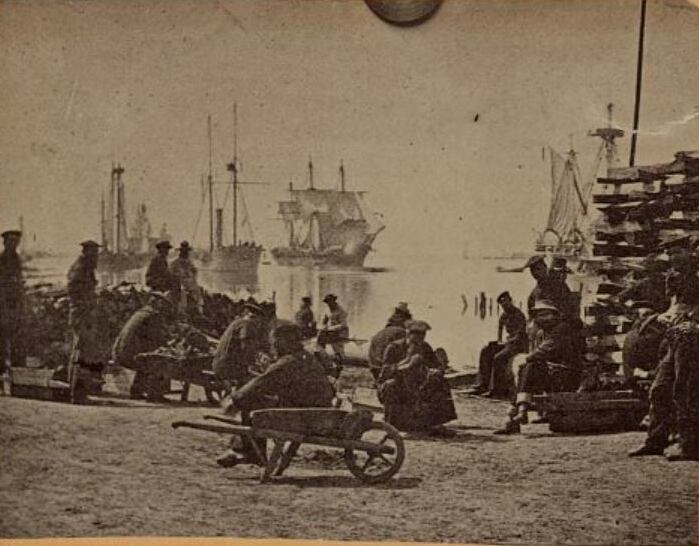

On Jan. 20, 1862, he received orders to “proceed up the Mississippi River and reduce the defenses” guarding the approaches to New Orleans. It took 18 days for him to sail from Hampton Roads to the rendezvous point at Ship Island, Mississippi, but nearly two months would pass before all was ready.

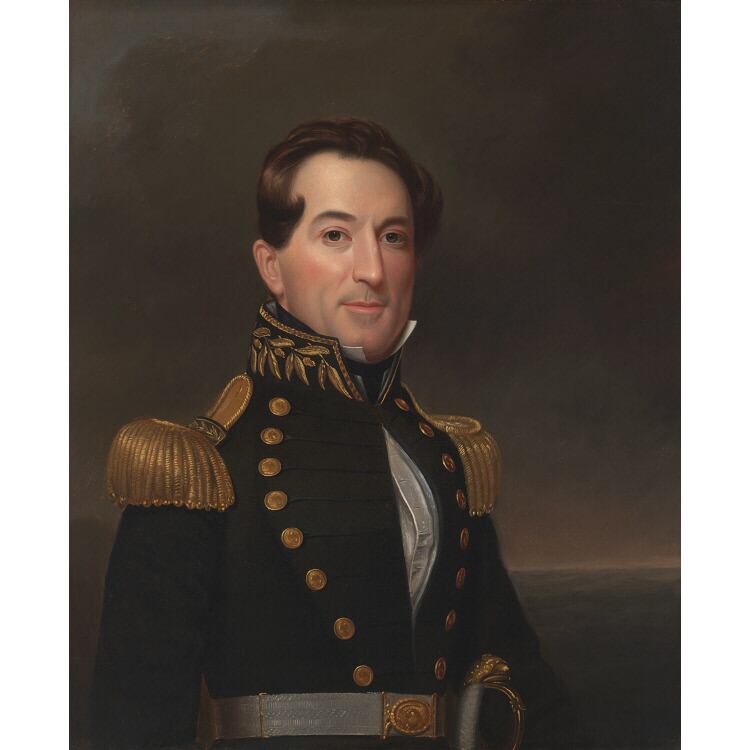

The struggle for New Orleans commenced on April 18, when the Union mortar boat flotilla — under the aegis of Farragut’s quasi-foster brother, Cmdr. David Dixon Porter — opened fire on the purportedly impregnable Forts Jackson and St. Philip, located across from each other about 70 miles below New Orleans.

The mortar vessels failed to significantly diminish the defensive capabilities of the two forts, which Farragut knew would be the case. Farragut quickly determined, demonstrating what Gideon Welles called his “innate fearless moral courage,” to run his flotilla past the forts even though they had yet to be reduced.

It was a momentous decision that contravened not only his orders, but the wishes of the Navy Department and the advice of many of his officers, principally Porter.

“As to being prepared for defeat, I certainly am not,” Farragut wrote his wife, adding that anybody who was “would be half defeated before he commenced.”

He would do all he could and trust God for the rest.

“I have to take this place,” he concluded. He would probably lose some of his ships, “but with some of my fleet afloat I shall eventually be successful. I cannot lose all. I will attack regardless of consequences, and never turn back.”

He never hesitated to risk all if the prize warranted it.

Before first light on April 24, Farragut advanced with 17 vessels. Fourteen succeeded in passing the forts, destroying eight Confederate vessels in the process and losing only one himself.

The forts no longer a threat, Farragut left Porter to negotiate their surrender and steamed upriver to occupy New Orleans on the 29th.

Farragut’s audacity on this occasion made him the foremost naval officer in the United States, a prominence he held until his death.

On July 11, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln approved a congressional resolution thanking Farragut and all who participated in the expedition. On July 30, Lincoln commissioned Farragut the U.S. Navy’s first rear admiral, to date from July 16.

Federal troops under Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler landed in New Orleans on May 1, supposedly freeing Farragut to proceed to his next objective. He had intended to continue up the Mississippi to link up with Union Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote, commander of the Mississippi River Squadron, which had just occupied strategic Island No. 10.

On May 5, however, he notified Welles, “As soon as I see General Butler safely in possession of [New Orleans], I will sail for Mobile [Alabama] with the fleet.”

Needing support troops for the Mobile expedition, Farragut lingered in New Orleans while Butler attempted to suppress the hostile inhabitants, particularly the women who expressed their contempt by insulting anyone in a blue uniform (see “Butler’s Infamous Order”).

One woman spat in Farragut’s face while he sat on a streetcar, and another emptied the contents of her chamber pot onto him as he walked below her balcony. Not wanting to be the cause of a riot and unable to move against Mobile, Farragut headed up the Mississippi.

Farragut proceeded to Vicksburg, with orders to run his fleet past the Rebel bastion’s daunting batteries. Before dawn on June 28, the ships set off, guns blazing. Eight of 11 ships succeeded, and none were lost.

Farragut, who escaped the ordeal with only a blow on the head from falling rigging, reported that the ships carried insufficient troops to hold the city.

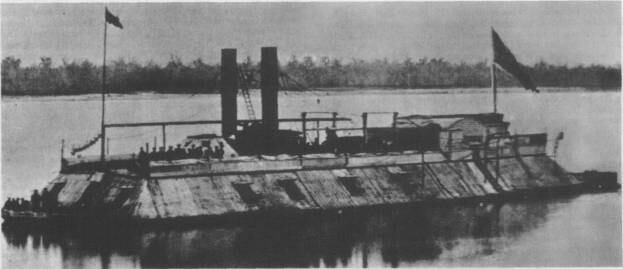

The Mississippi River Squadron, now under Flag Officer Charles H. Davis, began arriving July 1. Before it could launch a joint attack against Vicksburg, however, the Confederate iron-clad Arkansas descended from the Yazoo River on the 15th and successfully reached Vicksburg, passing through the combined Union fleets north of the city.

Furious, Farragut took eight vessels downstream that evening, hoping to sink the ironclad in the process. Supported by four of Davis’ ships, all of Farragut’s made it past the Confederate batteries, but Arkansas remained afloat and therefore still a threat.

Farragut headed for New Orleans on July 24, and then returned to the Gulf to secure every port except Mobile by the end of the year.

But disasters mounted in 1863. The Confederates recaptured Galveston and Sabine Pass in Texas; the Confederate screw sloop-of-war commerce raider Alabama sank the Union gunboat Hatteras; and the Confederate sloop-of-war commerce raider Florida escaped out of Mobile Bay.

Farragut took these reverses personally and quickly assumed responsibility for each of them. Yet there was little he could have done. He had been ordered to return to the Mississippi.

In December 1862, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks had arrived in New Orleans to replace Butler, bringing with him thousands of reinforcements and orders to proceed up the Mississippi.

The Federals reoccupied Baton Rouge, but 25 miles beyond by river was Port Hudson, where the Confederates had recently constructed a bastion just as formidable as Vicksburg on high ground above a sharp bend in the river. When Banks was unsuccessful in assaulting the fort by land, Farragut remained confident he would starve the garrison out of Port Hudson if he could blockade the Red River, thus eliminating one of the bastion’s critical supply lines to the north.

To accomplish that, Farragut would need to run his ships past Port Hudson. Even though it made him an easy target, he chose to make the run by daylight rather than attempting to navigate a 150-degree turn, a treacherous current, and a shifting sandbar in the dark.

It was March 14. Banks was supposed to help by creating a diversion but failed to do so, and bad fog finally forced Farragut to abort the effort. When Banks promised that his troops would be ready that evening, Farragut revised his plans. Rather than risk a recurrence of morning fog, he would make the attempt at night.

Another concern for Farragut was that his 18-year-old son Loyall was with him. As his ships moved past the bastion, Confederate guns opened fire. When a shot shrieked by, Loyall happened to duck.

Grabbing his son by the shoulder, Farragut admonished: “Don’t duck, my son; there is no use in trying to dodge God Almighty.”

The admiral would learn to his dismay the next morning that only his flagship, Hartford, and one gunboat had run the gantlet.

Four vessels had headed back downstream, and the Union steam frigate Mississippi — Matthew Perry’s flagship during his famed 1853-54 mission to Japan — had run aground and then been destroyed by its crew (something the Rebels disputed).

Two vessels proved insufficient to blockade the Red River, and the garrison at Port Hudson continued to enjoy ample rations.

Farragut remained on the Mississippi to assist Banks in capturing the bastion, which finally fell after a 48-day siege — the longest in American history.

Port Hudson’s capitulation on July 9, 1863, came five days after the Confederate surrender at Vicksburg.

President Abraham Lincoln declared: “The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea.”

After 19 months, Farragut had earned a well-deserved rest back in New York.

In early 1864, however, he returned to the Gulf of Mexico for an assault upon Mobile, where he would make his most lasting mark on history, with his illustrious “Damn the torpedoes!” declaration that brought about closure of the Confederacy’s top Gulf port for blockade runners.

Farragut’s willingness to lead where his subordinates feared to go made this victory essentially his alone. Congress created the rank of vice admiral, and Lincoln promptly nominated Farragut. Lincoln also directly benefited from Farragut’s success — Mobile was the first of a series of victories that helped him win reelection.

Farragut saw no further action in the war.

Congress created the grade of full admiral especially for Farragut, his appointment effective July 26, 1866. As commander of the European Squadron in 1867, he led a 17-month “goodwill” cruise.

After suffering a heart attack in 1869, he died the following summer in Portsmouth, N.H.

Despite a cold, pouring rain, more than 10,000 people — including President Grant — marched on Sept. 30, 1870, in Farragut’s funeral procession in New York.

Epilogue: A note on timely teamwork

Though often disappointed by Union generals, Farragut fulfilled their requests whenever possible.

After Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks’ May 27, 1863, assault failed to capture Port Hudson, he asked the admiral for heavy guns to help breach the earthen fortifications surrounding the town. Farragut quickly complied, and ordered Lt. Cmdr. Edward Terry of the Union’s wooden steam sloop Richmond on May 30 to command a naval battery ashore.

A site 748 yards opposite the Confederate center was selected and work commenced by June 4. After mounting the final cannon on the morning of the 9th, the sailors opened fire. They discharged their guns so rapidly that the following evening Banks requested additional ammunition from Farragut.

By June 13 they had dismounted two enemy guns and set fire to some buildings. The massive bombardment on the morning of June 14 intended to drive the Confederate cannon into hiding and out of action ended with a broadside from the four Dahlgrens fired over the heads of advancing blue-clad infantrymen.

The sailors knocked out another cannon by nightfall, but the attack failed.

Banks now turned his attention to his left flank, where sailors relocated one Dahlgren on the 18th and a second on the 27th.

Only 340 yards separated these two guns from Confederate sharpshooters, who quickly taught the seadogs the perils of fighting ashore.

Reinforcements for the sailors came in the form of Ensign Edwin M. Shepard and a 17-man gun crew from the Union’s ironclad river gunboat Essex. Terry turned over immediate command of the remaining two guns opposite the Confederate center to Shepard on July 2, but continued to supervise both detachments.

After 48 days the garrison capitulated. The Union column that entered the fortifications on July 9 to accept their surrender included a detachment from the U.S. Navy.

From all accounts of their service ashore, the sailors deserved this honor.

RELATED

Lawrence Lee Hewitt, who studied under the famed T. Harry Williams at Louisiana State University, is author or editor of 15 Civil War history books, including Port Hudson: Confederate Bastion on the Mississippi and Louisianians in the Civil War. He is currently based in Chicago.