MIDWAY ATOLL, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands — Deep-sea explorers scouring the world’s oceans for sunken World War II ships are focusing in on debris fields deep in the Pacific, in an area where one of the most decisive battles of the time took place.

Hundreds of miles off Midway Atoll, nearly halfway between the United States and Japan, a research vessel is launching underwater robots miles into the abyss to look for warships from the famed Battle of Midway.

Weeks of grid searches around the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands already have led the Petrel to one sunken warship, the Japanese aircraft carrier Kaga.

This week, the crew is deploying equipment to investigate what could be another.

Historians consider the Battle of Midway an essential U.S. victory and a key turning point in WWII.

“We read about the battles, we know what happened. But when you see these wrecks on the bottom of the ocean and everything, you kind of get a feel for what the real price is for war,” said Frank Thompson, a historian with the Naval History and Heritage Command in Washington, D.C., who is on board the Petrel.

“You see the damage these things took, and it’s humbling to watch some of the video of these vessels because they’re war graves.”

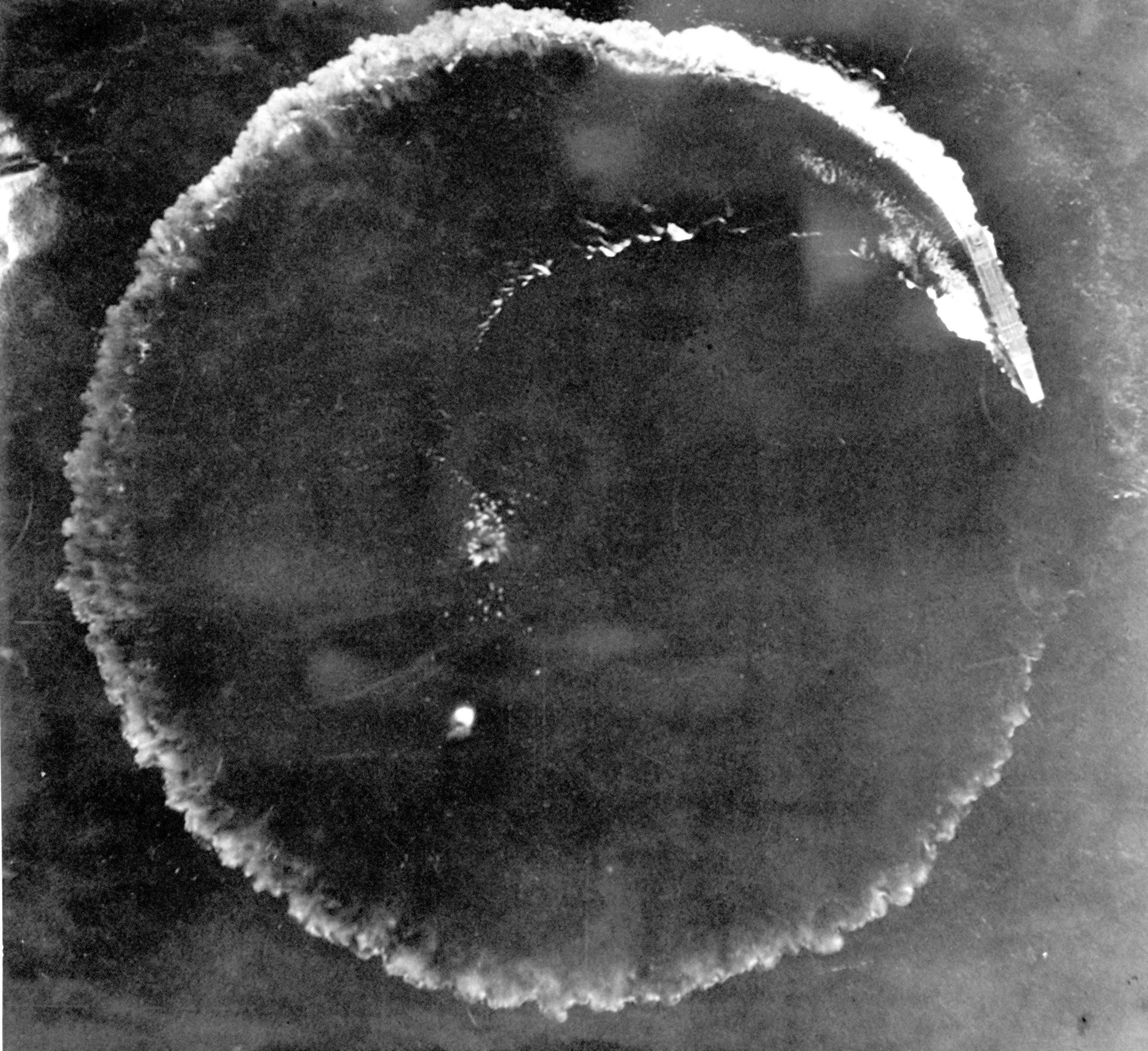

Sonar images of the Kaga show the bow of the heavy carrier hit the seafloor at a high rate of speed, scattering debris and leaving an impact crater that looks as if an explosion occurred in the ocean.

The front of the vessel is buried in mud and sediment after nose-diving about 3 miles (4.8 kilometers) to the bottom.

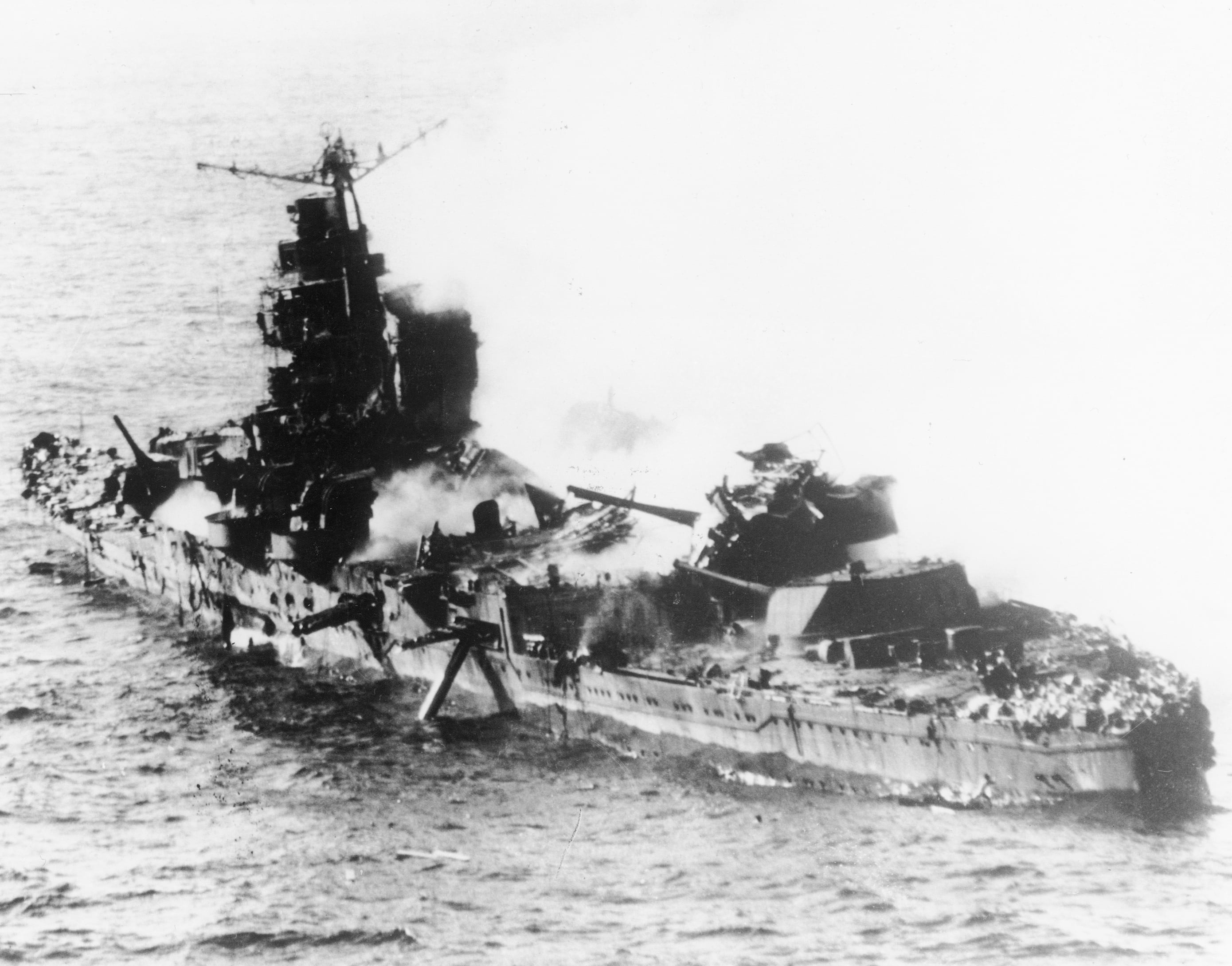

The U.S. bombs that struck the Kaga caused a massive fire that left it charred, but the ship stayed mostly together. Its guns, some still intact, stick out the side.

Until now, only one of the seven ships that went down in the June 1942 air and sea battle — five Japanese vessels and two American — had been located.

The expedition is an effort started by the late Paul Allen, the billionaire co-founder of Microsoft.

For years, the crew of the 250-foot (76-meter) Petrel has worked with the U.S. Navy and other officials around the world to find and document sunken ships.

It is illegal to otherwise disturb the underwater U.S. military grave sites, and their exact coordinates are kept secret.

The Petrel has found 31 vessels so far. This is the first time it has looked for warships from the Battle of Midway, which took place six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and left more than 2,000 Japanese and 300 Americans dead.

The attack from the Japanese Imperial Navy was meant to be a surprise, a strike that would give Japan a strategic advantage in the Pacific.

It was thwarted when U.S. analysts decoded Japanese messages and baited their enemy into revealing its plan.

As Japanese warplanes started bombing the military installation at Midway Atoll, a tiny group of islands about 1,300 miles (2,090 kilometers) northwest of Honolulu, U.S. forces were already on their way to intercept Japan's fleet.

U.S. planes sank four of Japan’s aircraft carriers and a cruiser, and downed dozens of its fighter planes.

One of the American ships lost was the Yorktown, an aircraft carrier that was heavily damaged and being towed by the U.S. on the battle’s final day when it was hit by torpedoes.

The other, the destroyer Hammann, went down trying to defend the Yorktown.

Retired Navy Capt. Jack Crawford, who recently turned 100, was among the Yorktown's 2,270 survivors.

Japanese dive bombers left the Yorktown badly damaged, with black smoke gushing from its stacks, but the vessel was still upright.

Then the torpedoes hit, Crawford told The Associated Press by telephone from his home in Maryland.

"Bam! Bam! We get two torpedoes, and I know we're in trouble. As soon as the deck edge began to go under, I knew . she wasn't going to last," said Crawford, whose later military career was with the naval nuclear propulsion program. He also served as deputy assistant secretary for nuclear energy in the Department of Energy.

The Yorktown sank slowly, and a destroyer was able to pick up Crawford and many others.

In May 1998, almost 56 years later, an expedition led by the National Geographic Society in conjunction with the U.S. Navy found the Yorktown 3 miles (5 kilometers) below the surface.

Crawford doesn't see much value in these missions to find lost ships, unless they can get some useful information on how the Japanese ships went down. But he wouldn't mind if someone was able to retrieve his strongbox and the brand-new sword he left in it when he and others abandoned ship 77 years ago.

He was too far away to see the Kaga go down.

A piece of the Japanese aircraft carrier was discovered in 1999, but its main wreckage was still missing until last week.

After receiving some promising sonar readings, the Petrel used underwater robots to investigate and get video. It compared the footage with historical records and confirmed this week it had found the Kaga.

Rear Adm. Brian P. Fort, commander of U.S. Naval Forces in Japan, extended thoughts and prayers to Japan.

“The terrible price of war in the Pacific was felt by all our navies,” he said.

The other three Japanese aircraft carriers — the Akagi, Soryu and Hiryu — and the Japanese cruiser Mikuma are still unaccounted for.

The Petrel crew hopes to find and survey all the wreckage from the battle, an effort that could add new details about Midway to history books.

Earlier this year, they discovered the Hornet, an aircraft carrier that helped win the Battle of Midway but sank in the Battle of Santa Cruz near the Solomon Islands less than five months later. More than 100 crew members died.

The Petrel also discovered the Indianapolis, the U.S. Navy’s single deadliest loss at sea.

Rob Kraft, director of subsea operations on the Petrel, says the crew's mission started with Allen's desire to honor his father's military service. Allen died last year.

“It really extends beyond that at this time,” Kraft said. “We’re honoring today’s service members, it’s about education and, you know, bringing history back to life for future generations.”

RELATED

Associated Press writer Mark Thiessen in Anchorage, Alaska, and researcher Jennifer Farrar in New York contributed to this report.