Before he was Unknown X-2858 Manila #2 Cemetery, Lt. Thomas James Eugene “Jimmy” Crotty was the youngest of five boys and a girl born to Irish immigrants in Buffalo’s old Fifth Ward in 1912.

He also was the captain of the Coast Guard Academy’s football team, president of his graduating class, and a gifted young officer who was sent to rescue passengers off the burning liner Morro Castle and later served as a special deputy on the Bering Sea Patrol.

And on July 19, 1942, Crotty, a hero of Corregidor, was dying of diptheria in the squalid Cabanatuan Prisoner of War Camp, soon to be given last rites at the edge of a mass grave and lost to his countrymen for 77 years.

“If he hadn’t been killed in World War II, Lt. Jimmy Crotty could’ve been a flag officer,” said Coast Guard Atlantic Area Historian William H. Thiesen. “It’s a real tragedy. He was an exceptional leader from his earliest days in uniform and all of that was cut short in the Philippines.”

On Friday, the historian stood in a Niagara hangar when an honor guard carried Crotty’s remains off a Coast Guard plane. And he’ll stand at Holy Cross Cemetery in Lackawanna when members of the armed forces and Crotty’s family tuck the lieutenant back into American soil to rest forever.

For the past dozen years, ever since Thiesen met a great-nephew of the dead Coastie, he’s been a detective, part of a sprawl of investigators in the Philippines, Hawaii and the mainland working to find whatever was left of Jimmy Crotty and bring him home to Buffalo.

“He represents so much to the Coast Guard,” said Thiesen. “Think of all the people who were lost at sea in World War II. They’re never coming home because they belong to the sea.

“Many don’t realize that the Coast Guard is a worldwide service that goes into harm’s way. Lt. Jimmy Crotty did his duty, just like they do today, and the Coast Guard has brought him home.”

If you look closely at the Coast Guard’s ensign — the American flag that’s draped with a cascade of bright streamers — you might spot a red one slashed with two white stripes.

That’s the Philippine Defense Battle Streamer and it hangs there only because of Jimmy Crotty.

He’s believed to have been the lone member of the Coast Guard to have fought the Japanese in the Philippine Islands after they invaded shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Eight months earlier, Crotty had received orders to report to the Navy’s Mine Warfare School in Yorktown, Virginia. After another advanced course at the Navy Yard in Washington, D.C., he became the Coast Guard’s top expert on mines, demolition and explosives, Thiesen said.

Nearly six weeks before the raid on Pearl Harbor, Crotty arrived at the Cavite Navy Yard in the Philippines, where the Navy attached him to In-Shore-Patrol Headquarters.

“At the time, Manila Bay had the largest minefield in the world,” said Thiesen. “It’s why the Coast Guard’s leading expert on mine warfare went there.”

Ten hours after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, they turned to the Philippines, landing troops north and south of Manila that quickly pushed back the outnumbered American and Filipino forces.

Japanese planes left Cavite Navy Yard ablaze on Dec. 10 and Crotty’s headquarters moved to Fort Mills on Corregidor Island.

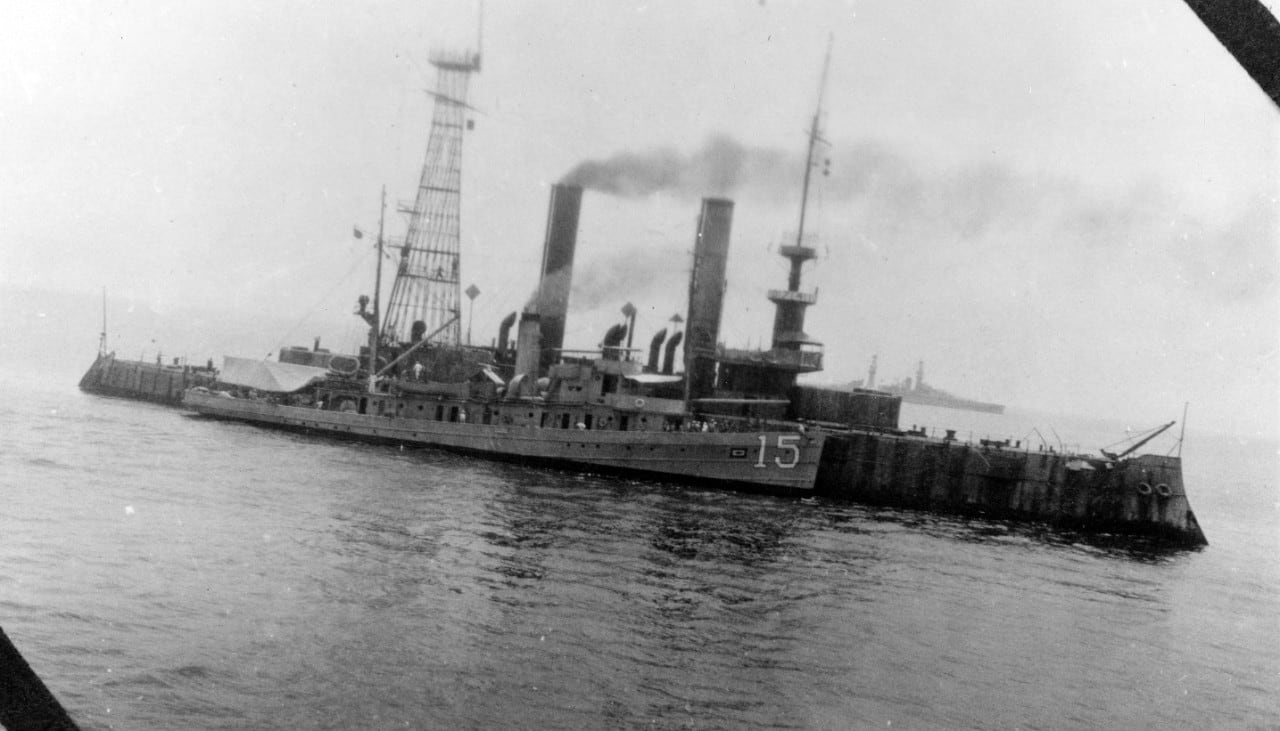

He became the executive officer of the Navy’s minesweeper Quail, with duties at sea and ashore.

To prevent American materiel from falling to the Japanese, he supervised the demolition of Sangley Point Naval Station and the damaged fleet submarine Sea Lion, which he packed with depth charges and detonated as perhaps the biggest Christmas cracker in history.

By early 1942, Quail was scuttling across Manila Bay, firing at low-flying Japanese aircraft, sweeping the waters to allow American submarines to surface in the black of night with critical supplies and seeding the waves with explosives to block the Japanese Imperial Navy from inching toward Corregidor, where defenders were expected to make a last stand before being relieved by American reinforcements.

But the reinforcements never arrived.

On April 9, 1942, besieged U.S. and Filipino troops on the Bataan Peninsula surrendered.

“The Rock” of Corregidor was honeycombed with 23 batteries — coastal defense guns, mortars, anti-aircraft positions and Sperry searchlights ― and Crotty was a trained gunnery officer amid a jumble of 14,728 U.S. and Filipino troops.

That’s how a Coast Guard officer ended up commanding Army artillerymen manning a 75-millimeter gun for 1st Battalion, 4th Marines ringing Malinta Hill, which rose over the eastern stretch of the island like an anvil.

It was struck by the hammer of Japanese forces on May 5, 1942. The invasion force that landed on Corregidor outnumbered the defenders five to one.

Thiesen told Navy Times that an eyewitness puts Crotty firing away at the oncoming waves of Japanese troops until the final charge.

The last position was overrun around 1030 on May 6.

Had he remained on the Quail, Crotty might’ve been one of the lucky 18 crewmen who motored the minesweeper’s 36-foot launch past the Japanese to reach Australia, a daring journey over more than 2,000 miles on ocean.

Instead, the lieutenant became the first Coast Guard POW since the War of 1812.

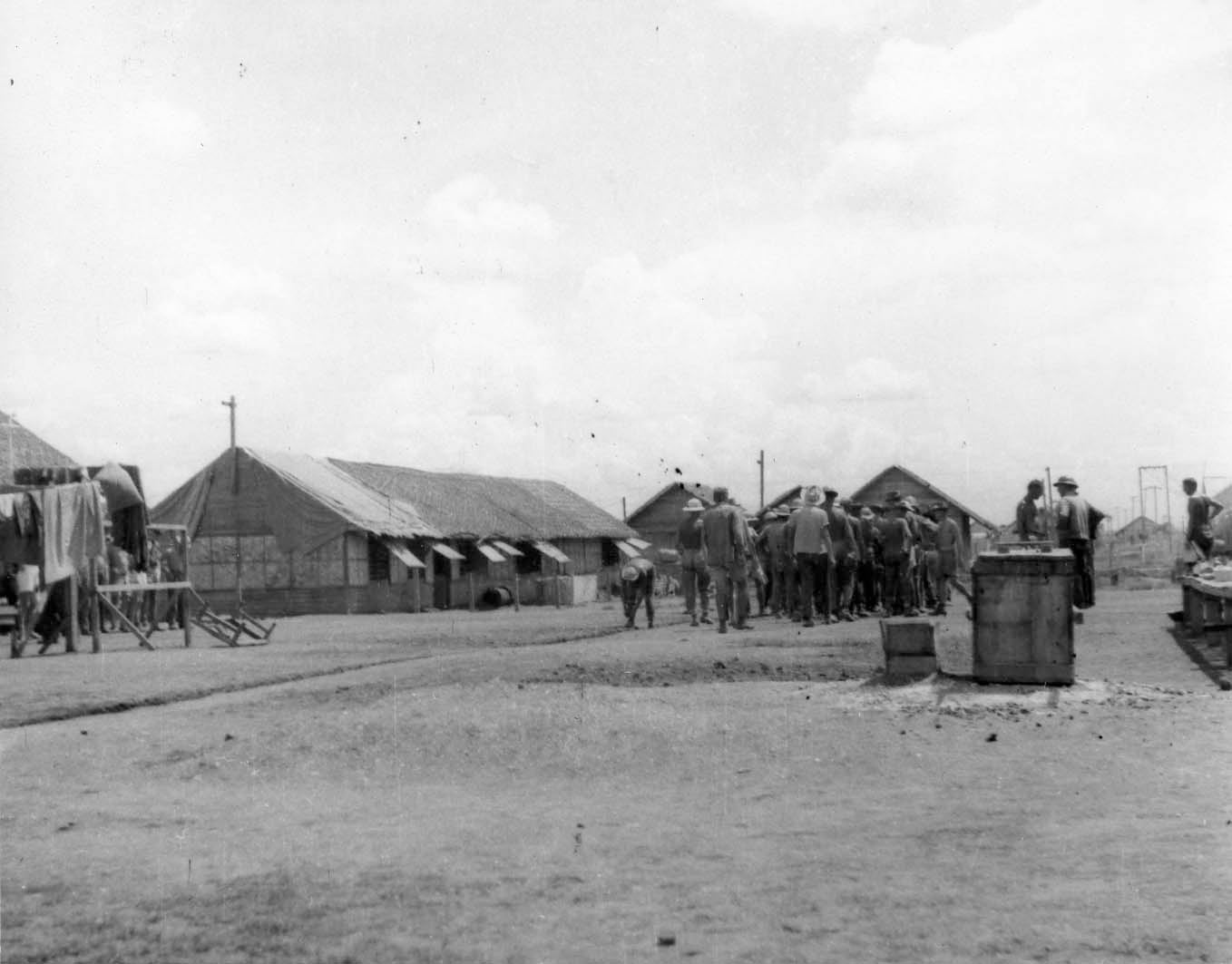

Crotty joined the ranks of POWs paraded through the streets of Manila, then squeezed into boxcars and shipped 50 miles into Ecjia Province. Disembarked, he was marched the final 10 miles to what would become the infamous Cabanatuan Prisoner of War Camp.

A report on Crotty’s case prepared by Hillary J. Sebeny, the World War II Historian at the Indo-Pacific Director of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, points to the camp’s abysmal living and sanitary conditions, where hunger competed with “rampant” disease to winnow the numbers of survivors from Bataan and Corregidor.

Sebeny’s file records Crotty entering the camp hospital on June 15, 1942, suffering from diphtheria, a bacterial infection spread by coughs and sneezes.

The disease creates toxins that attack the healthy tissues in the respiratory system, with a thick coating of dead cells building up in the nose and throat that makes breathing difficult.

Crotty died at around 0300 hours on July 19, 1942, according to a camp ledger.

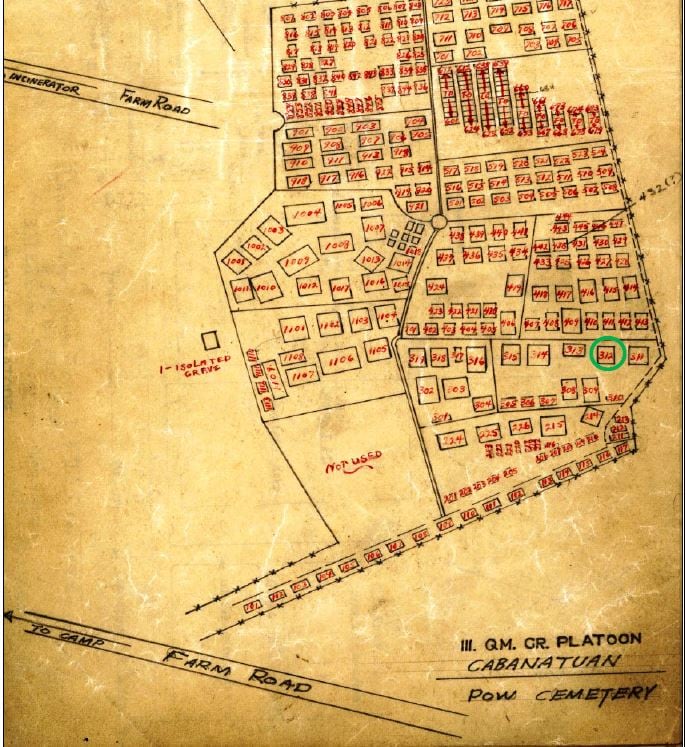

It had become the practice at Cabanatuan for prisoners to bury their dead in common graves, with one ditch shoveled out each day, according to Sebeny’s report.

Camp records reveal Crotty was interred in Common Grave 312 with other service members who had died between noon on July 18 and noon on July 19, 1942.

And there they would remain until after hostilities ended in 1945.

After the war, the Army’s 111th Quartermaster Graves Registration Platoon dug up the cemetery to remove all remains.

Using military IDs, dental records, ledgers and other evidence, the American Graves Registration Service identified a dozen servicemen in Common Grave 312 to rebury, but Crotty wasn’t one of them.

Those that couldn’t be paired with a name received a Cabanatuan unknown number, called an “X-file,” and returned to the cemetery.

To the U.S. government, Crotty was simply “Unknown X-2858 Manila #2 Cemetery.”

In 1948, Unknown X-2858 Manila #2 Cemetery passed through the Manila Mausoleum and Central Identification Point, but investigators still couldn’t match any remains to Crotty.

His remains received a new identification number but it didn’t matter. He was declared non-recoverable on Aug. 18, 1949 and, three years later, his bones were reburied in the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial and his name was stenciled on the Walls of the Missing, according to the DPAA file.

The only thing American officials knew was that there were more bodies in Common Grave 312 than were indicated in the camp records.

The same paperwork showed three of the remains the could be identified should’ve been buried in a different grave.

For a half-century, the armed forces had neither the evidence nor the science to solve the puzzle of Unknown X-2858 Manila #2 Cemetery.

But over the past two decades, advances in DNA testing began allowing scientists to match with great confidence the molecular genetic material in old bones to living relatives.

Armed with the new genetic testing methods, on May 30, 2017 DPAA ordered the disinterment of 23 unknowns found in Common Grave 312.

Unknown X-2858 Manila #2 Cemetery flew to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency Laboratory located at Hawaii’s Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam.

Staffed with dozens of anthropologists, archaeologists and forensic odontologists — dental experts — it’s the largest skeletal identification lab on the planet.

Sebeny’s report indicates that DPAA scientists relied on tooth and anthropological analysis, plus “circumstantial and material evidence,” to link the remains to Crotty.

They also had help from scientists at the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System, who matched mitochondrial DNA from Crotty’s great-nieces and great-nephews to his body.

On Sept. 10, 2019, DPAA declared Unknown X-2858 Manila #2 Cemetery to be Lt. Jimmy Crotty.

He was going home to Buffalo.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo ordered all state government buildings to fly their flags at half-staff on Saturday to honor Crotty’s sacrifice and legacy “as he is finally and rightfully returned home to Buffalo,” according to a press release.

The lieutenant’s funeral and burial are expected to draw several Navy and Coast Guard admirals, along with a throng of family members and aging service members who fought in World War II.

The highest-ranking officer there likely will be the 26th Commandant of the United States Coast Guard, Adm. Karl L. Schultz.

He graduated from the Coast Guard Academy 41 years after Crotty died at Cabanatuan.

In a Tuesday message distributed to all hands and emailed to Navy Times, the admiral said that Crotty embodied his service’s core values of honor, respect and, most especially, devotion to duty.

“As we celebrate his life and legacy, we also celebrate the lives of the more than 600 Coast Guard members we were not able to bring home from WWII,” Schultz wrote.

“He represents the proud legacy of the Long Blue Line of Coast Guard men and women who place themselves in harm’s way every day in the service to their country and fellow man.”

RELATED