The letter, signed by a GI attached to one of the Army’s far-flung radio stations, arrived from somewhere in Alaska.

“USO shows, talent, entertainers, or what have you haven’t reached us yet,” the soldier told editors of Down Beat, the jazz magazine in Chicago.

“About six months ago we saw our last jukebox. All we have are old movies and a good radio station that has only a handful of records. If you could help us in any way you would accrue the glory of a minor saint, at least in the eyes of us up here. We need records, all kinds.”

Fresh phonograph records at that point in the war — June of 1943 — were in short supply everywhere, not just in military bases and on the front lines but on the home front, too.

The American Federation of Musicians was in the 11th month of a 27-month strike against the recording industry, its members under orders to stay out of studios until compensated for songs played on jukeboxes and radios.

As the strike dragged on, soldiers and civilians alike grew weary of tunes recorded in the years before Pearl Harbor.

Then, in the same month Down Beat ran the letter from Alaska, a five-foot-three lieutenant named G. Robert Vincent came up with a novel idea to lift the spirits of homesick troops in lonely outposts around the world: The Army should seek the talents of America’s leading music figures and produce and distribute its own records.

The War Department instantly approved Vincent’s proposal. It put him in charge of the project and gave him $1 million plus a captain’s rank to get it going.

Rather than risk being branded unpatriotic, the musicians’ union president James Caesar Petrillo endorsed the plan too. He told members they could donate their performances, as long as no commercial use was involved. None of the records could be sold, it was agreed, and all would be destroyed when no longer of use to the military.

By November 1943, the first V-Discs — records solely for the troops — were being shipped to units far and near. A few months later, the Navy was making V-Discs too.

By the time the program ended in 1949, soldiers, sailors, and Marines had received more than 8 million copies of some 900 different discs, encompassing over 2,700 songs by virtually every major musical star of the day.

“This is Count Basie,” went a typical introduction. “We’re making some V-Discs for all you cats. Some real jump stuff. So here we go and hope you like it.”

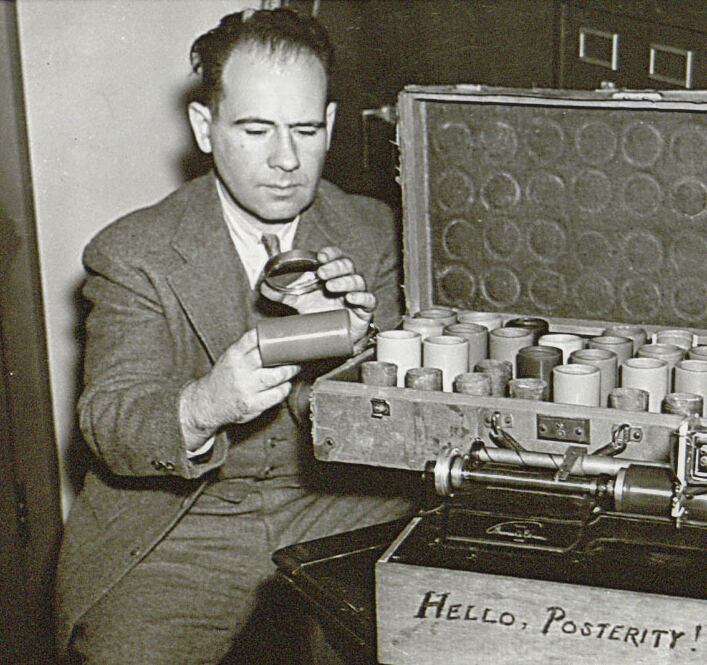

Two decades later, when Vincent established at Michigan State University academia’s largest recorded-voice library, he spoke with a New York Times reporter about his V-Disc days.

“Everybody thinks they were V-for-victory discs,” he said. “Actually I named them for myself, V for Vincent.”

Perhaps, the Times noted, he was joking. But there was no doubt that recording had been Vincent’s passion since his New York childhood.

At age 14, armed with an Edison wax cylinder recorder, he visited Theodore Roosevelt’s home on Oyster Bay and secured the only TR ad-lib ever preserved for posterity: “Don’t flinch, don’t foul, and hit the line hard.”

Hoping to gather sounds of World War I, Vincent quit school in 1916 and stowed away on a ship to Europe. He was a teenage dispatch rider in the French infantry when an artillery explosion knocked him unconscious. In the hospital he began deliriously speaking German (his mother was Austrian) and was promptly arrested as a spy.

Only with the help of the American ambassador did he get out of jail.

Sent home,Vincent joined the U.S. Army. By war’s end, he was a second lieutenant, back in France with his portable recorder.

A few years later, with a Yale diploma in hand, he landed a job in New Jersey as one of Thomas Edison’s sound engineers.

Pearl Harbor stirred Vincent at age 43 to try to be a soldier again.

Too old, he was told. But the Army let him record the sounds of troops preparing to go to war, and before long he was playing his recordings in the White House for a grateful Franklin Roosevelt.

His commission as a lieutenant and an assignment to the Army’s radio section shortly followed.

Once the V-Disc scheme won the support of Petrillo and the Pentagon, Vincent faced a major technological challenge.

The Army had been sending its military disc jockeys 16-inch, 33-rpm shellac discs — mostly transcriptions of American radio shows. But shellac records were brittle. Four of every five of the army’s discs arrived looking like jigsaw puzzles.

Shellac was also scarce. The lac beetles that secrete the resin-like substance are indigenous to Southeast Asia, and the region had fallen to the Japanese in 1942.

After extensive testing, Vincent and his aides settled on a new polyvinyl resin developed in Canada called Formvar, akin to the vinyl that by the 1950s formed virtually all phonograph records.

The results were superb. Fidelity was high and breakage low. Like standard records, the V-Discs spun at 78 rpm and could be used on soldiers’ spring-wound record players.

But V-Discs were bigger than ordinary records, 12 inches wide instead of 10, and had narrower grooves. That meant longer playing times, up to 6 ½ minutes per side on a V-Disc compared with less than 4 minutes on a standard record.

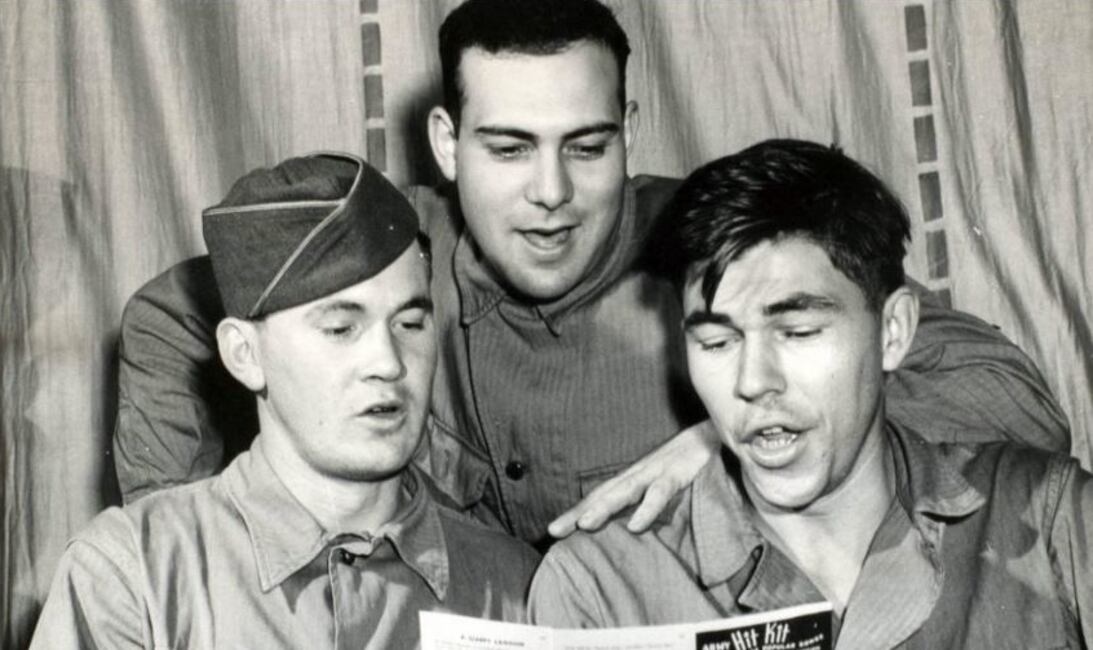

The first monthly shipment from RCA Victor’s pressing plant in Camden, New Jersey, included 1,780 “Hit Kits,” each containing 30 V-Discs, a total of 53,400 records.

By war’s end, the Camden plant was producing 300,000 V-Discs a month.

With their red-white-and-blue labels, the V-Discs were an instant and enduring hit in barracks, mess halls, and officers’ clubs.

“We visited many, many places in England and France,” recalled band leader Spike Jones in 1945, “and everywhere we went, we saw the men playing V-Discs. We heard them on the boat going over and on the boat coming home. We played them on the LST boat crossing the channel, and we saw them being played everywhere in France, including in foxholes.”

Vincent’s New York staff, a few servicemen with a lot of recording experience, relied on an array of sources for their music. Hundreds of recordings were transcriptions of commercial radio programs.

All but a few of Bing Crosby’s 60-plus VDisc recordings, for example, were lifted directly from broadcasts or rehearsals of NBC’s Kraft Music Hall. Many other V-Discs were reissues of commercial records cut before the strike (like Duke Ellington’s “Mood Indigo”) or recycled from movie soundtracks (like Lena Horne’s “Good for Nothin’ Joe,” from the 1943 movie Stormy Weather).

The most significant recordings, though, and the ones today most treasured by collectors, were the hundreds of original performances captured in special sessions run by the V-Disc team.

Some took place in New York studios borrowed from the record companies. Others had V-Disc engineers dragging 400 pounds of gear into concert halls, nightclubs, and military bases across the country.

Much of the music was, and still is, unique: Tommy Dorsey and Judy Garland together for “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”; Lionel Hampton, of “Flying Home” fame, now “Flyin’ on a V-Disc”; Duke Ellington’s 5-minute and 42- second version of “In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree”; Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, after feuding for years, patriotically uniting their orchestras for a V-Disc special called “Brotherly Stomp.”

For two years, Benny Goodman recorded nothing but V-Discs. Frank Sinatra sang dozens of songs for V-Disc that he recorded commercially either many years later or never at all, including “The Way You Look Tonight,” “Long Ago and Far Away,” and “Come Rain or Come Shine.”

It was a 1943 V-Disc session that brought forth Fats Waller’s final recordings before his death, including richly praised performances of “Ain’t Misbehaving,” Duke Ellington’s “Solitude,” and, on the organ, a brooding rendition of “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child.”

There was a tune for every taste. Soprano Lily Pons trilled for V-Discs as well as for the Metropolitan Opera.

The “Caruso of Mountain Music,” the Grand Ole Opry’s Roy Acuff, sang “The Great Speckled Bird” and “Pins and Needles (In My Heart).” (Acuff was so well known wherever America’s military went that Marines dug in on Okinawa at one point heard Japanese soldiers taunting them, “To hell with Roosevelt! To hell with Babe Ruth! To hell with Roy Acuff!”)

Black and white servicemen alike savored the V-Discs of Louis Jordan, a rhythm and blues pioneer who scored such hits as “Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby,”“I Like ’Em Fat Like That,” and “Caldonia (What Makes Your Big Head So Hard?).”

His VDisc “You Can’t Get That No More” told zoot-suited hepcats on the home front they could not escape the woes of war: “No more standing on the corner day and night / Uncle Sam says you got to work / Or you got to fight.” Food is rationed, Jordan noted, and “the fine chicks is cuttin’ out each day / Joining the Waves and the Spars and the Wacs / No, fellows, you can’t get that no more.”

Capt. Glenn Miller and his Army Air Force Band saluted an on-the-wall fantasy, “Peggy, the Pin-Up Girl” with “the chassis that made Lassie come home.”

V-Discs helped circulate a number of the war’s famous catch phrases. Included among Nat King Cole’s V-Disc hits was “Straighten Up and Fly Right,” one of the war’s most repeated lines. Officers barked it to enforce discipline. Friends used it when a buddy drank too much.

And for a while everyone was parroting Spike Jones’s comic recording that went, “Ven der Fuehrer says / ve ist der master race / ve heil — PFFFT! — heil — PFFFT! / right in der Fuehrer’s face.”

The songs the servicemen liked most, though, never mentioned bombs or foxholes or Hitler.

The Armed Forces Network polled troops based in England and found they overwhelmingly preferred ballads that stirred memories of a loved one across the sea.

Nearly all the top favorites were on V-Discs: “Amor” by Bing Crosby, “I’ll Walk Alone” by the bands of both Harry James and Louis Prima,“Long Ago and Far Away”by Frank Sinatra,“I’ll Get By (As Long As I Have You)” by both Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald. The song most requested of all by the fighting men, Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas,”appeared on a V-Disc, as did his “Silent Night,” “Adeste Fideles,” “Jingle Bells,” and “I’ll Be Home for Christmas.”

The No. 1 non-holiday song,“Stardust,” graced six V-Discs, two by Artie Shaw and one apiece by Glenn Miller, Marie Greene, Edgar Haynes, and the composer, Hoagy Carmichael.

The end of the war did not mean the end of V-Discs.

The Army and the Navy valued the program as a morale booster and kept it going until May 1949. That year, as required by the musicians’ union, metal masters of V-Disc recordings were gathered and destroyed. The deal called for the records to perish too.

But many came home in the footlockers of returning warriors. The FBI cracked down, but only in cases involving lots of records.

A record company employee in Los Angeles served jail time for possessing a secret hoard of 2,500 V-Discs.

Fortunately for music lovers, two large collections survived.

The Library of Congress apparently has a copy of every V-Disc. And an almost complete set was kept by the officer who ran the Navy’s V-Disc program, the late E. P. “DiGi” DiGiannantonio.

Decades later, after getting approval from the artists or their estates, he assembled and sold cassettes and CDs made from the collection. For the last dozen years, the Collectors’ Choice label has distributed the V-Disc releases.

As a result, a few hundred V-Disc songs are now accessible, to the delight of critics and collectors.

But nothing is as special as an original, a fact sensed even by the enemy: A German oberleutnant, negotiating the surrender of his troops to American forces in 1945, asked if anyone had a Count Basie V-Disc.

RELATED

This story originally appeared in the July/August 2007 issue of World War II Magazine, a sister publication to Navy Times. To subscribe, click here.