Bored with life in a small Nebraska town during the Depression, Donald Stratton was just the sort of youngster the U.S. Navy was looking for prior to World War II.

Stepping into the local post office in 1940, Stratton was all ears when a recruiter began what became a successful sales pitch. The recent high school graduate traded his civvies for blues and eventually found himself reporting for duty at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard to board his first ship — the battleship Arizona (BB-39).

World War II: Commissioned in October 1916, the battleship Arizona was a 31,000-ton behemoth that was home to more than 1,700 men. It must have been a remarkable sight for someone from Red Cloud, Nebraska. What was your first impression of the ship?

Stratton: They were working on it at dockside. There were so many hoses…saltwater hoses, welding cables, everything all over the decks.

They brought us aboard and assigned us to different divisions—we were standing fire watch pretty near every night when the welders were working on board. I remember thinking at the time, “Oh boy, this [isn’t] really what I anticipated.”

But the chaplain [Captain Thomas L. Kirkpatrick] came around and said, “This isn’t always the way it is….My friend, when we get out to sea you’ll notice quite a bit of difference.”

And sure enough, we did. After a few days in the shipyard, they put her in dry dock. We had to go over the sides and scrub it down and paint it. To an old flatlander like me, when I saw the battleship out of the water it was quite a sight. I was awestruck.

WWII: To which division were you assigned on the ship? What were its responsibilities?

Stratton: The 6th Division. That was a boat deck division on the port side.

In the Navy, the starboard side is always assigned to the odd-numbered divisions; port, the even ones. Most of our time was spent scraping and cleaning some of the boats. We had to holystone the decks and keep everything shipshape.

We had two 50-foot motorboats, two 40-foot launches, whaleboats, the captain’s gig and the admiral’s barge on the boat deck. That was a deck behind the smokestack. I was assigned to clean up the foremast. The stack was right there, and when they blew tubes the smoke would gather on the paint in the yardarms and the foremast, and we’d have to scrub it down.

WWII: The refit on your ship was completed in January 1941, and you set sail for Hawaii on Jan. 23. Were you excited about going to Pearl Harbor?

Stratton: Sure, it was an experience. I’d never been there before. A lot of people had never been there, and it was just something you could talk about.

WWII: Keeping a battleship in fighting trim was a constant job. The entire crew must have been kept pretty busy on the voyage to Pearl Harbor.

Stratton: Yes. We had our usual duties, but I also had a chance to become familiar with some of the ship’s armament.

It had a 5-inch .25[-caliber] anti-aircraft gun that I was assigned to. We practiced loading and firing. We actually didn’t fire, just practiced loading. The shells were all fixed ammunition, and they weighed probably 70 or 80 pounds.

The loader had to load them into the breech and then the rammer had to ram them home. My job was as a sight setter for the gun. My battle station was in the director [room] on the foremast.

WWII: With the threat of war, the U.S. Pacific Fleet was moved from San Pedro, California, to Pearl Harbor in May 1940, representing the greatest concentration of military might the United States possessed at that time. Eight battleships, three aircraft carriers and countless cruisers, destroyers and other smaller craft were anchored at Pearl. It must have been quite a spectacle.

Stratton: It was very impressive. Almost the whole crew was topside as we came in. The place was lush and green, and with memories of the Dust Bowl still pretty vivid I remember thinking that the folks back home just wouldn’t believe this.

WWII: Did you ever consider the possibility of war with Japan?

Stratton: I don’t think anyone really thought about it. I think the first inkling we got was when we went on maneuvers for a couple of months or so and they only allowed us five gallons of water every day. We figured something must be up because they were seeing what would happen if they did [have to] ration the water.

WWII: Duties on board ship started pretty early, even on a Sunday. How did your day begin on Dec. 7, 1941?

Stratton: My quarters were in what they called the casemates, near where the 5-inch broadside guns were. There were four of these quarters on the port side, and that is where I was when reveille was sounded. After cleaning up a bit, I went for breakfast around 7 a.m. Most of the crew was wearing shorts and T-shirts. That was the uniform of the day, except for the Marines and the boat crews.

After breakfast I [headed] to the sickbay to visit my friend, Harl Nelson.

Editor’s note: Harl Coplin Nelson, seaman first class, was among the 1,177 to die on board Arizona that morning.

WWII: What sort of relationship did you have with Harl?

Stratton: He was just another sailor in the 6th Division. He and I had been working on the incinerator. Everyone was temporarily assigned these sorts of duties. It usually lasted for three months. Harl and I met burning garbage.

WWII: Were you able to visit Harl before the attack started?

Stratton: No. I had just stepped out of the mess area near the casemate on the bow of the ship when I could hear sailors yelling and hollering.

I took a look and they were all pointing at Ford Island. We could then see all sorts of planes. Then I saw either the dive tower or the water tower on Ford Island go over. The planes would peel off, and we could see their Rising Sun insignias and then we could see bombs bursting.

I asked myself, “What the hell is going on?”

WWII: It was just after 8 a.m. when the Japanese attack began. When you realized this was no drill, what did you do?

Stratton: I made an about-face and started for my battle station, which was one deck above the bridge. First I went up the ladder to the radio shack, and from there took another ladder to the bridge and finally a third ladder to get up to the sky control platform. I must have been quick because I was already there when General Quarters finally sounded.

WWII: You were finally facing an enemy in earnest. What was happening at your battle station?

Stratton: There was a gunnery officer up there. There was a port on top of the director where you could look out to get a visual picture and try to set the range and flight path of the target.

My job was to crank whatever the gunnery officer would say into this gauge I had in front of me and send the estimated coordinates to the gun crew below. Once the coordinates were set, the crew would switch the gun to automatic so it would point to wherever the director told it. I was responsible for four of the 5-inch guns.

WWII: There were a tremendous number of guns on the ship. How many of you were spotting up there?

Stratton: There was a starboard director on the other side with the same amount of men. It took about eight or nine men to man the inside of my director, and they had all kinds of sailors with binoculars sighting planes coming in. The big gun director was on the same level for the 14-inch guns. There were probably at least 50 men in the port director and a similar number on the starboard side.

WWII: Did you go right into action?

Stratton: Yes. It was all happening very quickly and I didn’t have much time to think. We were firing. There were only 50 rounds of ammunition in the ready box behind each gun, and I could see that some of the crews had to break the locks off the boxes to load their guns.

We were firing at the planes — more or less at the high altitude bombers. We knew that the torpedo bombers and the dive bombers would be covered by the .50-caliber machine guns.

We worried about the high altitude bombers, [but] we couldn’t reach them. Our shells were bursting before they ever reached their altitude.

WWII: At approximately 8:10 a.m., Arizona was hit by an 800-kg armor-piercing bomb just forward of No. 2 turret. The bomb penetrated the ship’s deck and went off a few seconds later in the forward powder magazine. The subsequent blast gutted the ship, and the foremast and forward superstructure began to collapse. What do you remember of this blast?

Stratton: We were hit once before — aft on top of No. 3 turret — and it bounced over the side. One went through the afterdeck and didn’t explode. Then one hit up above on the starboard side — it was big. It shook the ship like an earthquake.

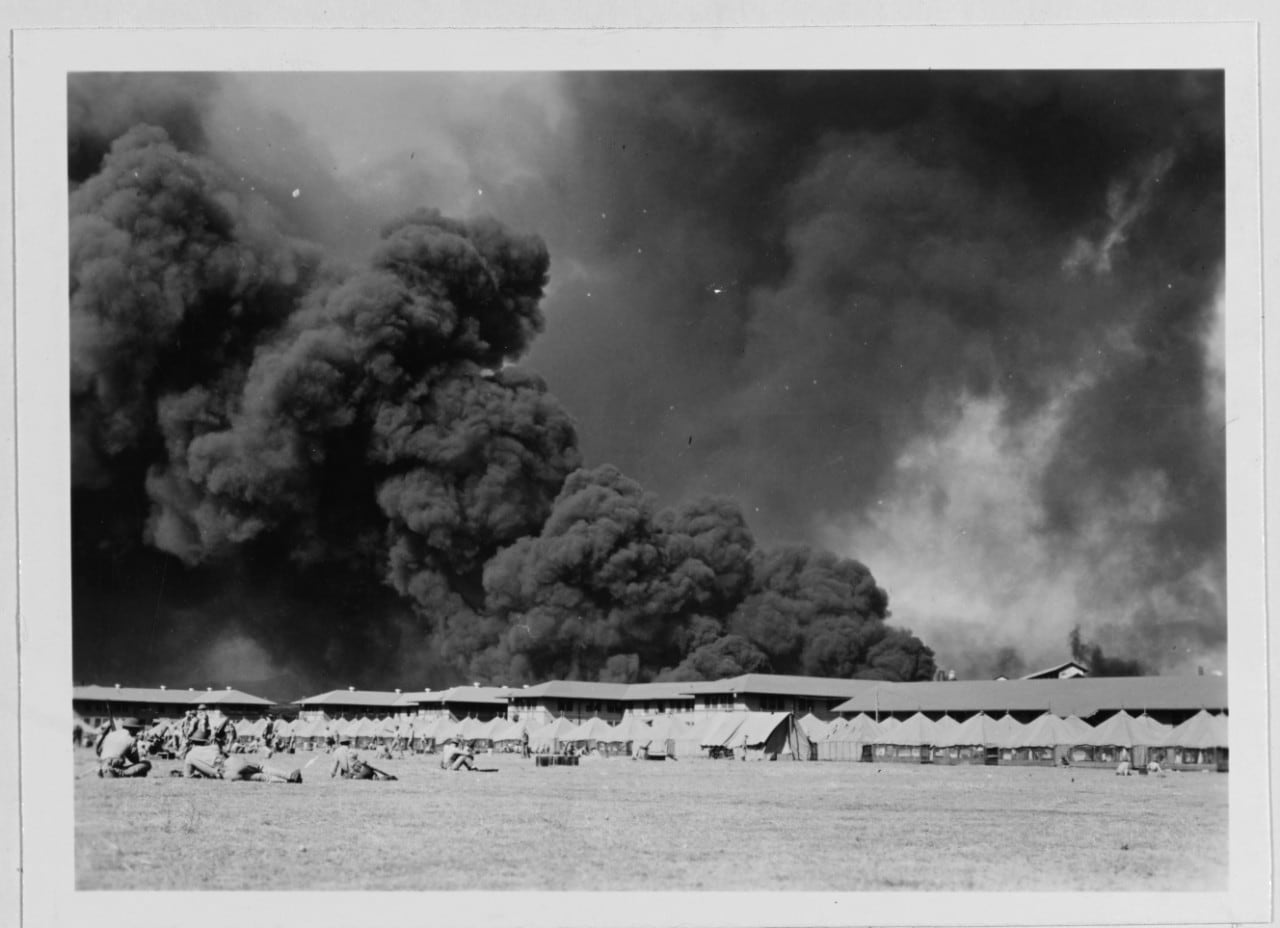

Then all at once there was a big explosion, which just raised the ship pretty near clear up out of the water and then back down. There was a ball of flame that went about 500 to 600 feet in the air, and it just engulfed the whole foremast up there where we were and the whole bow of the ship.

WWII: What happened inside the director at this point?

Stratton: It just rattled us around like we were inside of a tube or something. As soon as I came to my senses, I tried to hide under some of the equipment to keep away from the blaze, but I still got burned. The fire came right into the director.

WWII: Did you or anyone else try to escape the fire by going outside onto the platform?

Stratton: No, we stayed in there for a little protection. A couple of the people in the director jumped out and I never did see them again.

WWII: How long was it before you went onto the platform?

Stratton: When the fire kind of squelched down a little bit. There was a little sea breeze that blew the smoke away. The fire control director and I got out on the platform. All the deck…inside of the charthouse and the ready boxes: Everything was red-hot. We couldn’t lay or sit down.

WWII: From your director, you were one of only two survivors of the blast. Were you injured?

Stratton: Yes. I knew I had been burned and was in terrible pain. My legs were burnt from my thighs clear to my ankles. My T-shirt had caught on fire, and my back, both my arms and left side were burned pretty bad — so was my face.

All the hair on my head was burned off, and part of an ear was gone.

WWII: Could you see what was happening below you on the rest of the ship?

Stratton: [Pause.] I’m not going to say anything. That was so terrible I don’t even want to say anything about it.

WWII: With your injuries and the condition of the ship, it is something of a miracle that you survived. How did you get off the ship?

Stratton: Vestal was tied up alongside and we got this sailor’s attention [Jon Georg]. He threw us a heaving line and then attached another heavier line to it so we could pull ourselves across to safety.

I was all burned to hell, and I remember that as we got ready to leave I grabbed the skin on my arms and just pulled it off like a big long sock and threw it on the deck.

WWII: Crossing over to a ship like that must be difficult, even under the best of circumstances. How did you do it?

Stratton: Well, you know, you’re 40 feet in the air and the water below you is on fire. It was about 60 to 70 feet across to Vestal. I didn’t have much choice, so I just started pulling myself hand over hand. I had to have a lot of help from up above, the good Lord. It was quite a feat, especially when your hands were as raw as mine were.

WWII: Do you know if any others on board the ship used this lifeline to reach safety?

Stratton: I think there were only six of us. I was either the third or fourth to go over. Two of the others who crossed died of their wounds that night.

WWII: Do you remember how long it took the group to get across?

Stratton: No. I would have no idea at all. Vestal was lower than we were as a ship, so we were going kind of downhill a little bit. You have to realize that Arizona sank to the bottom, too, and was at about 18 feet. That brought us down a little bit to the level, but still going downhill a little bit. When you get to the middle of a line going across like that, with the weight you start going back uphill again.

The last 10, 15 or 20 feet were the hardest.

WWII: What happened once you finally made it aboard Vestal?

Stratton: Nothing really. We just kind of all huddled together for a little while. They were trying to figure out how to get us off the ship to a hospital on shore. We were there for quite a little bit. Finally a shore boat came alongside. We were loaded on and taken to the pier.

WWII: When the shore boat arrived at the pier, what did you do?

Stratton: We had to get up on the dock, which was kind of a chore because the tide was down some. We reached up and grabbed with our hands—burns and all—to get ashore. Then they put us in an open-air truck and took us to the…naval hospital there on the island.

WWII: Up to that point, it seems as if, despite your wounds, you were looking out for yourself. Did the situation improve at the hospital?

Stratton: It was kind of chaotic, but the staff was pretty well organized. They were doing a good job when they finally got to us. There was a lot of damage to a lot of people; a lot of things going on.

WWII: What was the extent of your injuries, and what type treatment did you receive?

Stratton: Over 70 percent of my body was burned. I got the best treatment they could provide for such injuries. There were lots of sulfa drugs and morphine.

One problem was that we were so badly burned the nurses and orderlies could not tell who had been given a shot of morphine and who hadn’t. Finally, some nurse figured out to use lipstick to mark us.

They’d put an “X” on you once you had been given a shot and then put down what time it had been given. There were so many people in my condition, it was hard to keep track of all of it.

WWII: How long was your treatment at the hospital?

Stratton: Not long after we had first been treated, someone came into the room and said, “Some of you people are going to go to the States.”

“I’ll go,” I called out.

“No,” he answered, “we don’t think you can, you’re not in good enough shape to make it. You probably wouldn’t survive the trip.”

WWII: So did you stay?

Stratton: No. I told the man I could make it easy.

“Well,” he said to me, “if you can stand up while we change the linen, we’ll think about it.”

So I stood up while they changed the linen. I didn’t get up for a long time after that. They sent me back to the States. I arrived on Christmas Day and was taken to a burn unit at Mare Island Naval Hospital [California]. I was glad to be back in the States. All of us were.

I think we had peas and other stuff for our Christmas dinner.

WWII: What was your treatment like at Mare Island?

Stratton: They gave me a lot of antibiotics. After a while they decided saltwater baths would help. They would put double sheets under me and take me to the bathroom. Then they would get four corpsmen, one on each corner of the sheets, who would pick me up and set me down in this tub of saltwater. It seemed to help.

The first time was a little rough, but after two or three you’d start to look forward to it. It was still tough. I couldn’t move. I couldn’t feed myself. I couldn’t do anything. They had a canopy over my bed to keep me warm, but no sheets or blankets; all the burns were left exposed to the open air.

WWII: How many men were in that burn unit? Were they all from Arizona?

Stratton: I don’t know how many beds there were, probably 20. They were all full. The guys were from different places, though, not just my ship.

WWII: How long were you in the burn unit?

Stratton: For about nine months. Then I was transferred to Corona, California, where the Navy had taken over a hotel for convalescence. It was nice. We had a golf course, swimming pool and mineral baths. It was very enjoyable once I could stand up and get around.

When I first got on a scale, I weighed 92 pounds. I had weighed 165 or 170 on the morning of the attack.

WWII: Were any of your family able to visit you while you were at Mare Island or Corona?

Stratton: No. The fact is I didn’t want them to come out. They knew I had been burned. Some of the nurses would write letters for us.

It had been pretty rough on my parents. First they got a notice that I was lost, and then they finally got one saying I was in the hospital but had been badly burned.

WWII: Did you return to service after your convalescence?

Stratton: I was medically discharged in September 1942. My whole left side was kind of disabled. My left arm was in pretty bad shape, and my left leg as well.

After being back home for a little over a year, though, everything was in pretty good shape, so I decided to go back into the Navy. The only way I could get in was through the draft.

I had a couple of friends on the draft board and they signed me up, and the Navy sent me to Omaha.

WWII: Why did you want to get back into the Navy?

Stratton: There was just not a lot going on at home and, you know, it wasn’t any different from 1940 when I graduated, as far as jobs were concerned. There may also have been a little bit of wanting to get revenge, you know. I went to boot camp in January 1944. I did well at the camp and they wanted me to stay there, but I wanted to go back to sea.

After graduation they sent me to Treasure Island, where I was when they received a request from USS Stack [DD-406] for gunner’s mate third class. The destroyer… needed crew. I was picked and eventually reported aboard.

WWII: Like most ships that fought in the Pacific, Stack stopped at Pearl Harbor en route. What was it like for you when you passed Arizona’s remains?

Stratton: Well, it was just one of those things. I welled up a little bit; I still do even now when I think about it. It’s quite a memory — a sad memory.

WWII: You were headed for a war zone. Given what you had already experienced, were you at all worried about that?

Stratton: I don’t know that I thought a lot about it. It was just one of those things you did when you’re in the Navy, the Army, the Marines. I participated in quite a few of the landings. I was part of the invasions of New Guinea, two in the Philippines and at Okinawa.

WWII: Does anything in particular stand out in your mind regarding your time on board Stack?

Stratton: We had submarine contact several times while I was on board. One time when General Quarters sounded, I jumped out of my bunk, and just as I got topside there was a big flash right in front of my face. My first thought was, “Oh man, we’re hit again.” It was like a flashback. It was kind of spooky. Once I calmed down, I found out it was an impulse charge that had launched a depth charge over the side.

WWII: The U.S. destroyers were pretty busy during the Okinawa operation, supporting the landings and providing pickets for the fleet. Several ships were attacked by kamikazes. How was it for you?

Stratton: We were on picket patrol between Okinawa and Japan for quite a number of days. We were losing quite a few destroyers to kamikazes. We had radar and would make contact with the planes coming in and contact for other ships and tell them what was on the way. We survived, but I remember they got four or five destroyers one night.

WWII: How did it all end for you?

Stratton: In October 1945, I was transferred to electric-hydraulic school and was discharged on Dec. 4, 1945. Given everything I had seen, I probably should have been more excited, but I seem to remember it as just one of those days.

Nothing more to do — the war was over, so let’s get out of this United States Navy and do something else.

WWII: You had quite a remarkable experience during nearly four years in the Navy. Although it has been more than 60 years, do you still think about it?

Stratton: I think about it every day. I have no animosity against the Japanese people, but I can’t forget what happened.

When I go to these reunions and there are Japanese pilots there that were doing the bombing, they ask if I’ll get up there and shake hands with them. I don’t do that. I never will do that.

You have to understand my position. There’s a thousand men down on that ship that I was on and I’m sure they wouldn’t do that, and I’m sure they wouldn’t want me to do it. I know that I’m very fortunate to be here. I just can’t help but think people should be more aware of what happened that day and how many lives were taken. How many of those sailors and Marines on board that ship right now don’t even know what happened to them or why it happened or who it was? It seems like an awful, awful waste of life for something that people are going to forget about.

We have so many people [today] who don’t appreciate their liberty and wouldn’t fight for it. A total of 1,177 men were lost when Arizona sank on the morning of Dec. 7. Many of the 334 crewmen who survived were ashore when the attack began.

Donald Stratton is one of only six men on board the doomed ship still alive to tell his story.

RELATED

David Lesjak writes the “WWII Today” column for World War II magazine. For further reading, see Battleship Arizona: An Illustrated History, by Paul Stillwell. This Q&A originally appeared in the December 2006 issue of World War II, a sister magazine to Navy Times. To subscribe, click here.