For most people today, Christmas is a time of food, family and festivities, when attention turns from work and woes to fellowship and celebration. Yet it has not always been so. In fact, Christmas of 1776 marked one of the most harrowing days in American history – when the fate of the fledgling republic itself hung in the balance.

Often remembered as Washington’s crossing of the Delaware, it pitted the ragtag Continental Army against perhaps the most feared fighting force on Earth, the German Hessians, whose services had been paid for by Britain. Yet the outcome would ultimately hinge as much on cold, ice and disease as on fighting prowess.

America’s waning prospects

Washington’s forces needed some good news. After they ran the British out of Boston in March of 1776, things began going from bad to worse.

The British chased Washington out of New York, then across New Jersey. By year’s end, Washington’s army was shrinking, and morale was low.

The British troops were ensconced in New York, well-fed and warm. They left German troops in charge of Trenton, New Jersey. Washington was expecting the forces of Generals Horatio Gates and Charles Lee to join him, but they were delayed by winter weather and lack of confidence.

The tide begins to turn

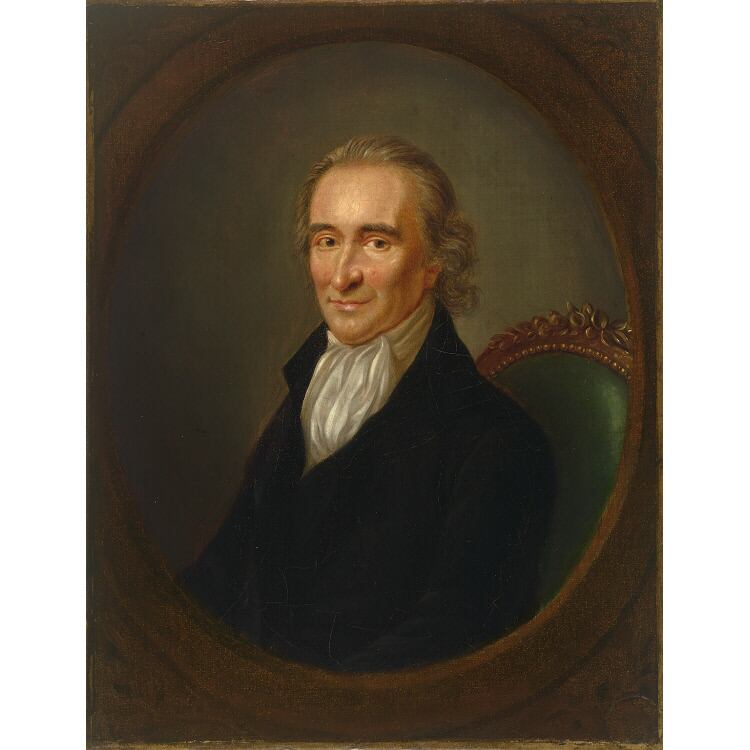

The first hint of reprieve arrived in the form of Thomas Paine’s “The American Crisis,” published on Dec. 19, with its famous lines, “These are the times that try men’s souls… . Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered… but the harder the conflict, the great the triumph.”

Washington ordered it read to the men.

Finally, the troops of Gates and Lee arrived, followed by militiamen from Philadelphia, providing Washington with a total force of about 6,000, many whose enlistments would expire at year’s end. On Christmas Eve, provisions arrived, further enhancing morale.

Crossing the Delaware

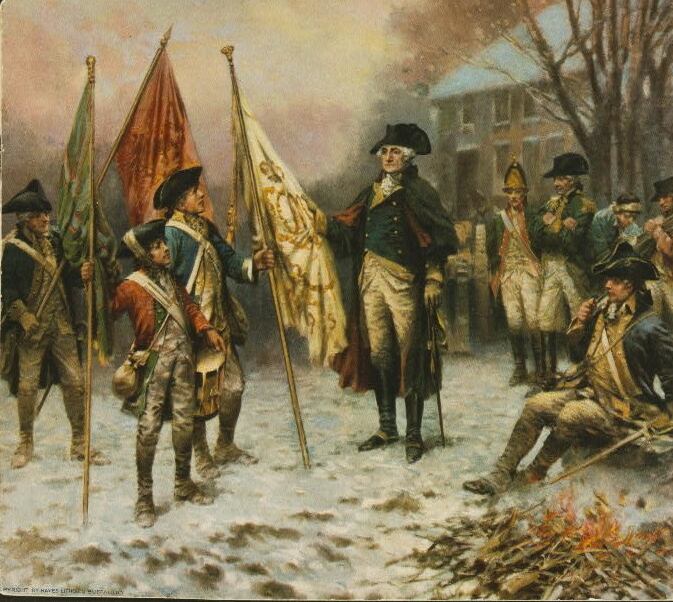

Washington’s plan was to make multiple crossings of the Delaware River in boats.

On Christmas morning, he ordered the troops three days’ food and fresh arms. The crossing would begin as soon as darkness fell. However, the weather deteriorated over the course of the evening, as drizzle changed into freezing rain and snow.

Henry Knox, Washington’s chief of artillery, had organized the crossing, which would be imperiled by floating ice. Men who got wet faced grave risks of frostbite and freezing to death.

Because of the ice and bad weather, the crossing, which was to be complete at midnight, was not finished until early the next morning.

The Battle of Trenton

The commander of the German troops in Trenton had received warning that an attack was coming, but he dismissed it, in part because lone farmers had been harrying the Germans for days, alternately drawing them out with gunshot and then retreating.

Against all odds, the Dec. 26 surprise attack succeeded, throwing the Germans into confusion. When they tried to organize a counterattack, the Americans fired on them with muskets, killing their commander and sowing further discord.

As a result of the battle, the Americans captured about 900 Germans and a large cache of supplies. Against orders, many American troops began enjoying captured rum, with the result that some fell into the water as they returned across the river.

Further crossings

While the attack and another foray a few days later did little to imperil the British forces in New York, they did restore the morale of the American troops. Many whose terms of service were ending elected, thanks in part to a congressional bounty, to remain.

After a third successful crossing, Washington and his men made their way to Princeton, where another successful attack forced the enemy back to New Brunswick. Thereafter the Continental Army established its winter encampment in Morristown in early January.

The real killers

Yet the seasonal cessation of hostilities did not bring an end to suffering and death. Throughout the Revolutionary War, far more troops died of disease than in battle. Common scourges included smallpox, typhus, dysentery and malaria. Of course, enemy troops were subject to the same diseases.

Factors such as poor sanitation and crowded living conditions created a favorable environment for the transmission of infectious disease, while poor hygiene and malnutrition lowered host resistance to infection.

In this respect, the war reprised a perennial theme of history – disease took more lives than combat. In his seminal book, “Plagues and Peoples,” historian William McNeill demonstrates the decisive historical role of diseases such as smallpox in Mexico, bubonic plague in China and typhoid fever in Europe.

Disease also deviled the American troops the following winter at Valley Forge, again multiplied by poor living conditions. The winters of 1779 and 1780 in Morristown were still worse, due to supply shortages and yet harsher weather. Several regiments even mutinied – a fate Washington had previously managed to avoid.

Victory in perseverance

Against great odds, Washington managed to keep the army together, and eventually the Americans triumphed, as much through dodging decisive defeats and refusing to surrender as through any military prowess.

As such chapters in the War of Independence illustrate, America has known many bleak Christmases, and when it comes to negotiating difficult times, the stubborn spirit of its people has often proved its redemption.

RELATED

Dr. Richard Gunderman is Chancellor’s Professor of Radiology, Pediatrics, Medical Education, Philosophy, Liberal Arts, Philanthropy, and Medical Humanities and Health Studies at Indiana University. He is also John A Campbell Professor of Radiology and in 2019-20 also serves as Bicentennial Professor. Gunderman is the author of more than 700 articles and has published 12 books, including “We Make a Life by What We Give” (Indiana University, 2008), “X-ray Vision” (Oxford University, 2013), “Essential Radiology” (3rd edition, Thieme, 2014), and “We Come to Life with Those We Serve” (Indiana University, 2017). Published in 2019 are “Pediatric Imaging” and “Tesla.”