The Jan. 3 targeted assassination of Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps Commander Maj. Gen. Qassim Suleimani significantly hiked direct hostilities between the United States and the Islamic Republic of Iran. It marks the first acknowledged intentional killing of a senior adversary during four decades of hostilities between Iran and the United States.

It is highly likely that United States possessed detailed intelligence about Suleimani’s travel plans, destination, and routes. This could be simply the result of superior electronic intelligence gathering and tracking the flight of his aircraft to Baghdad. Former U.S. commanders and intelligence officials said that the attack “specifically relied on classified ‘informants, electronic intercepts, reconnaissance aircraft and other surveillance.’”

The MQ-9 Reaper missile strikes were launched while the Quds Force’s commander and his convoy departed Baghdad International Airport soon after his arrival — although the base from which the drones operated has not been identified and the reason for Suleimani’s flight to Baghdad hasn’t been fully disclosed.

According to an Iraqi general, Suleimani and Mohammed Redha al-Jabri, a senior official in Iraq’s state-sponsored Popular Mobilization Forces, arrived by plane at Baghdad International Airport from Syria.

Two cars stopped at the bottom of the airplane steps and picked them up. The fatal U.S. strike occurred soon after Suleimani and his party deplaned and as they were departing the airport.

The strike reportedly was the second attack at the airport within hours. An earlier attack on late Thursday involved three rockets that did not appear to have caused any injuries.

What sparked the decision to kill Suleimani?

On Dec. 27, more than 30 rockets struck K-1 Air Base in Kirkuk, wounding four U.S. service members and killing an American contractor. Blame soon fell on Katai’ib Hezbollah, a militia that operates as part of the Iranian-backed Popular Mobilization Forces.

Two days later, U.S. forces struck back at Katai’ib Hezbollah posts in Iraq and Syria, killing and wounding dozens of fighters, including senior militia commanders.

Following funerals for many of the militiamen, on New Year’s Eve a mob of their sympathizers stormed into Baghdad’s Green Zone and began assaulting and besieging the U.S. Embassy there.

They burned the embassy’s reception area, planted militia flags on its roof and scrawled graffiti on its walls.

No injuries or deaths were reported and the militia members withdrew on New Year’s afternoon without testing the armed Marines guarding the compound.

A Pentagon statement later blamed Suleimani as the leader who “had orchestrated attacks on coalition bases in Iraq over the last several months,” including the lethal strike on K-1, and “approved the attacks on the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad.”

President Donald J. Trump already had warned that Iran would “be held fully responsible” for the embassy assault.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated that he, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper and Gen. Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, traveled “to brief the President on the activities that have taken place in the Middle East over the course of the last 72 hours.”

Secretary Pompeo insisted that the United States “will not stand for the Islamic Republic of Iran to take actions that put American men and women in jeopardy.”

More importantly, he explained the reason for retaliatory airstrikes and foretold the intent to “take decisive action.”

Then on Jan. 1, Pompeo’s State Department issued a Level 4 Do Not Travel Warning and noted that “Due to risks to civil aviation operating within or in the vicinity of Iraq, the Federal Aviation Administration has issued a Notice to Airmen and/or a Special Federal Aviation Regulation.”

At the heart of his concerns was the understanding that traveling to Iraq would put an American citizen at risk of terrorism, kidnapping or armed conflict.

“Anti-U.S. sectarian militias may also threaten U.S. citizens and Western companies throughout Iraq. Attacks by improvised explosive devices (IEDs) occur in many areas of the country, including Baghdad,” it warned.

“On Dec. 31, 2019, the Embassy suspended public consular services, until further notice, as a result of damage done by Iranian-backed terrorist attacks on the Embassy compound. U.S. Consulate General Erbil remains open and continues to provide consular services. On October 18, 2018, the Department of State ordered the suspension of operations at the U.S. Consulate General in Basrah. That institution has not reopened.”

Between mid-May 2019 and Jan. 3, the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad had issued nine Demonstration and Security Alerts.

In the wake of Suleimani’s assassination, President Trump announced that the Iranian “was plotting imminent and sinister attacks on American diplomats and American military personnel, but we caught him in the act, and terminated him.”

Initially, Pompeo also indicated that the strike had thwarted an “imminent” attack in the region, but declined to detail the intelligence on which he based his statement.

Special Representative for Iran, Brian H. Hook, told Al Arabiya that he had seen “all of the intelligence” on the action and suggested that “American personnel and facilities in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria and beyond” were the planned targets.

Suleimani "was actively developing plans to attack American diplomats and service members in Iraq and throughout the region,” added a Pentagon statement, which called the strike a “decisive defensive” action aimed at deterring future Iranian attacks.

Targeting enemy commanders is lawful and we’ve done it before

On April 18, 1943, the United States targeted and destroyed the aircraft carrying Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the attack on Pearl Harbor and the commander of Combined Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy, while it was preparing to land at Balalae Airfield on Bougainville in the Solomon Islands.

Admirals Chester W. Nimitz and William F. Halsey, Jr. — acting on decoded intercepts of Yamamoto’s planned itinerary, which had been read by Navy code breakers — authorized a joint force strike, led by long range Army Air Force P-38 Lightnings, part of AirSlos (Air Forces, Solomons), and commanded by Adm. Marc A. Mitscher.

The fighters waited over water near Yamamoto’s destination and ambushed the landing Japanese transport bombers.

It is unclear if President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized Operation Vengeance and there is no evidence trail pointing to his direct involvement.

Iran failed its fundamental obligation to protect diplomats and embassies

Iran has a documented history of intentionally refusing to comply with international law.

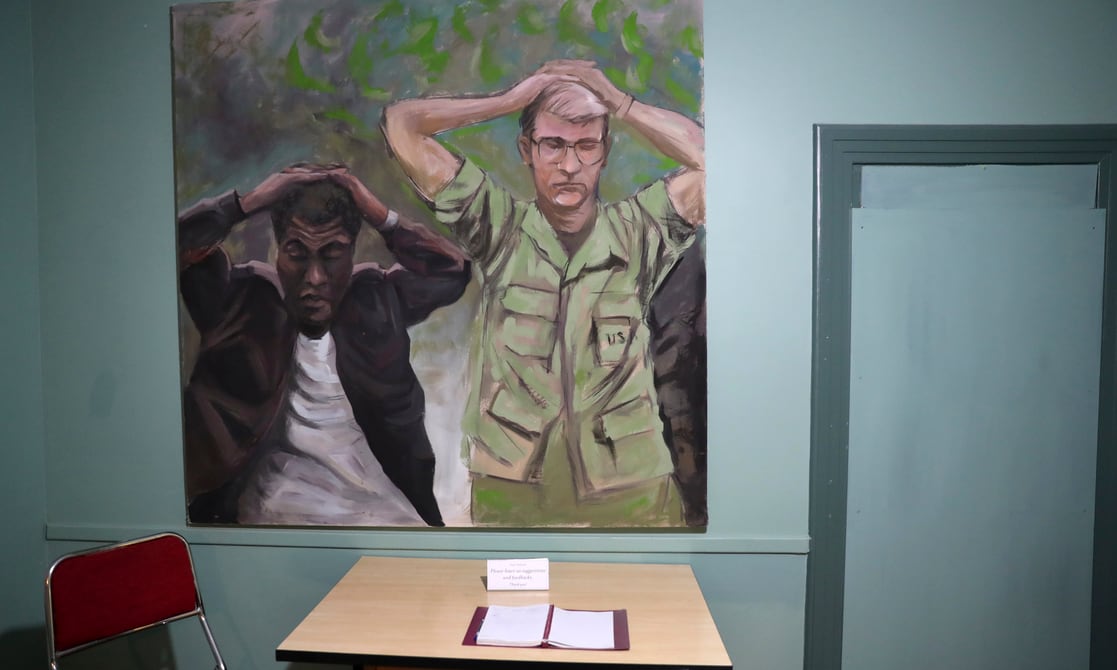

Forty years ago, on Nov. 4, 1979, the US Embassy in Teheran was seized and U.S. diplomats and consular personnel held hostage.

It is axiomatic that there was no more fundamental prerequisite for relations between states than the inviolability of diplomatic envoys and embassies.

While in the current crisis the embassy was located in Iraq, not Iran, it is apparent that Iranian forces may have been involved.

The recent involvement of Iranian-backed militias in Baghdad rekindled concern that seizing U.S. diplomats and consular personnel would trigger another lengthy hostage crisis. This is an unacceptable risk in U.S. foreign policy.

The attacks on the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad occurred 40 years after the taking of the US Embassy in Tehran.

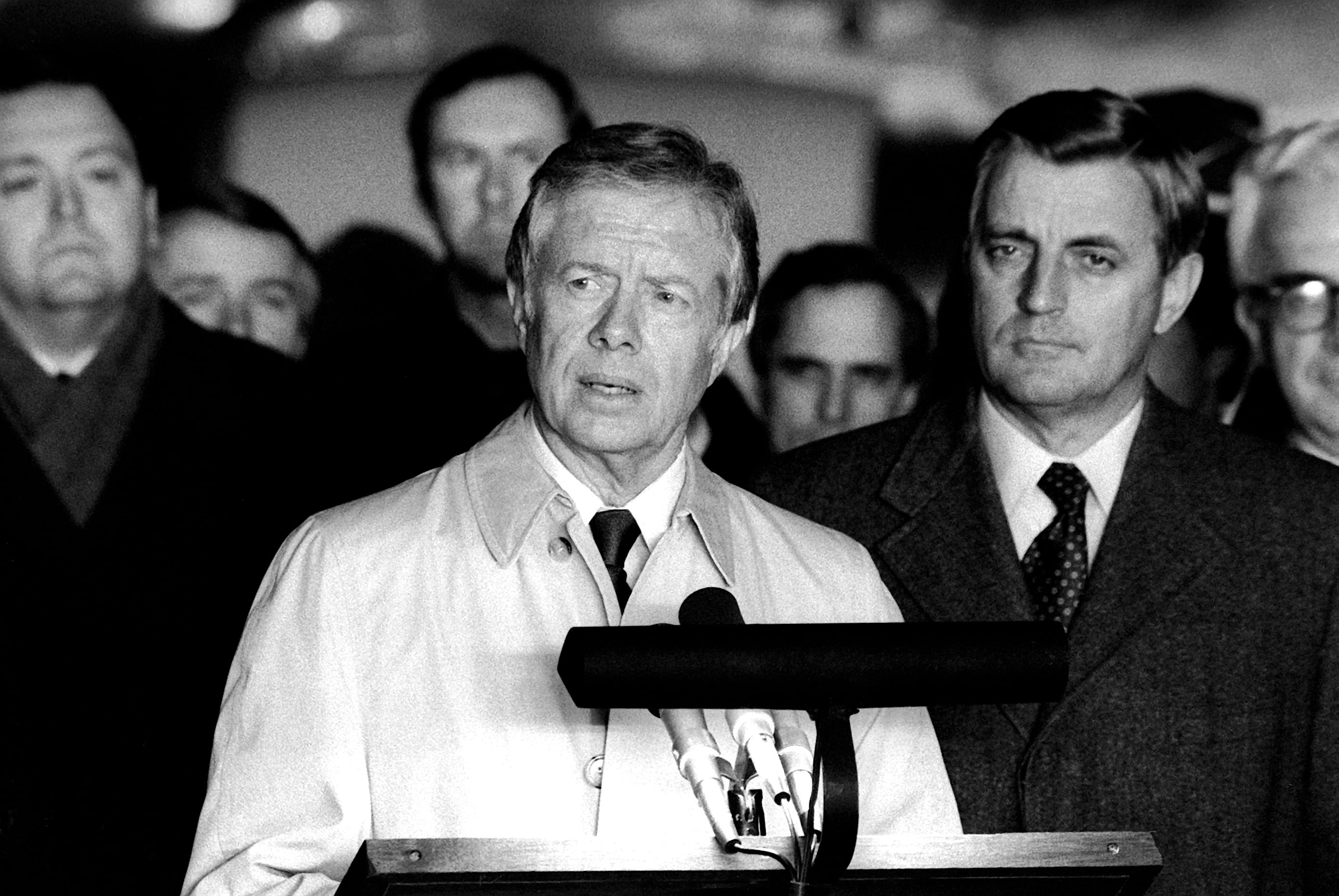

It has been suggested that the proximate cause of the 444-day Iran hostage crisis was the failure of President Jimmy Carter’s administration to remove all diplomatic personnel and close the embassy when the White House granted the deposed Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, to enter the United States to receive care for terminal cancer.

President Carter apparently relied on an understanding or representations by Iran that it would honor established legal protections afforded to U.S. diplomats and Embassy staffers.

The Carter administration could have reduced the risk of the illegal Iranian acts had the embassy been closed down in anticipation of the admission of the Shah. U.S. personnel and classified documents could have been removed and protected from seizure and the spectacle of the hostage standoff.

Apparently, there were no contingency plans to respond even though President Carter was concerned about the risk presented by his reluctant decision to allow the Shah of Iran to enter the United States in the fall of 1979.

The International Court of Justice has provided an overview of the action in United States of America v. Iran:

The case was brought before the Court by Application by the United States following the occupation of its Embassy in Tehran by Iranian militants on 4 November 1979, and the capture and holding as hostages of its diplomatic and consular staff. On a request by the United States for the indication of provisional measures, the Court held that there was no more fundamental prerequisite for relations between States than the inviolability of diplomatic envoys and embassies, and it indicated provisional measures for ensuring the immediate restoration to the United States of the Embassy premises and the release of the hostages. In its decision on the merits of the case, at a time when the situation complained of still persisted, the Court, in its Judgment of 24 May 1980, found that Iran had violated and was still violating obligations owed by it to the United States under conventions in force between the two countries and rules of general international law, that the violation of these obligations engaged its responsibility, and that the Iranian Government was bound to secure the immediate release of the hostages, to restore the Embassy premises, and to make reparation for the injury caused to the United States Government. The Court reaffirmed the cardinal importance of the principles of international law governing diplomatic and consular relations. It pointed out that while, during the events of 4 November 1979 … [Iran] had however done nothing to prevent the attack, stop it before it reached its completion or oblige the militants to withdraw from the premises and release the hostages. The Court noted that, after 4 November 1979, certain organs of the Iranian State had endorsed the acts complained of and decided to perpetuate them, so that those acts were transformed into acts of the Iranian State. …

However, the International Court of Justice did not render final judgment due to the release of the hostages on Inauguration Day of 1981 and the settlement of all claims.

Now what?

In addition to combatants and their civilian contractors, it is possible that reprisal attacks by Iran could be aimed at:

- Civilian airliners flying in the Gulf region or possibly worldwide, as in the case of Pan Am 103. It was destroyed by a bomb over Lockerbie, Scotland, killing all on board on Dec. 21, 1988. It was traced back to Libyan operatives, their motive most likely as a reprisal for losing a series of scuffles with the U.S. Navy in the Gulf of Sidra dating back to 1981.

- Commercial surface vessels in the region, particularly in the Persian Gulf and the adjacent waters near the coast of Iran. There had been multiple attacks on tankers in these waters during 2019. Also, during the Tanker War of the late 1980s, there were attacks on tankers in the Persian Gulf by both Iraq and Iran, including the use of mines and missiles. The U.S. Navy destroyed Iranian ships and platforms involved in the attacks on merchant ships and U.S. warships.

- Warships, most likely U.S. Navy vessels, in the Persian Gulf.

- Environmental damage, such as intentional pollution of waters or land. Iraq engaged in similar destructive conduct during its Gulf War with the U.S.-led coalition.

- Cyberattacks on US. agencies and firms, which likely would trigger retaliatory cyber strikes targeting Iranian nuclear enterprises and other assets important to Tehran.

- Terror attacks on civilian population centers and transportation systems, particularly in Western Europe, Japan, and possibly the United States.

But the White House has shown with the assassination of Suleimani that it can move swiftly, nimbly and decisively to the right along the spectrum of conflict.

Any Iranian strategist now needs to calculate carefully the moves Tehran should make, understanding that the U.S. has the worldwide capacity to keep escalating the stakes, including the destruction of their economy, nuclear infrastructure and large portions of their armed forces.

RELATED

A retired Navy Judge Advocate General’s Corps captain, Lawrence B. Brennan is an adjunct professor of Admiralty and International Maritime Law at Fordham Law School. He has litigated and investigated many ship collision and casualty cases both for the Navy and in private practice. He was a federal litigator for the U.S. Department of Justice. But what a lot of people don’t know is that he also was the attorney on board the aircraft carrier Nimitz when it launched eight helicopters as part of the Iranian hostage rescue mission on 24 April 1980. He was counsel for the Navy’s probe into the fatal crash on board Nimitz that sparked the service’s “zero tolerance” policy for drugs. He spent more than three decades implementing, drafting and teaching the Rules of Engagement, too.