Iran repeatedly denied that it was responsible for the deaths of all 176 people on board a Boeing 737-800 airliner.

But now Iran has reversed course and admitted it was responsible for firing surface-to-air missiles that took down the Ukrainian passenger jet immediately after takeoff from Tehran Imam Khomeini International Airport on Wednesday.

Nine prior commercial flights had departed from the major Iranian airport without incident.

It is important for the world to address Iran’s continued denial of intent in its fatal attack.

RELATED

Iran’s crisis management

Hours before the surprising Iranian public about face, I began writing about what Iran needed to do next.

To me, it was in Iran’s best interest to admit to the international community that it destroyed the commercial aircraft and killed everyone on board.

It is a fundamental rule of crisis management and litigation to recognize the inevitable and begin to promptly address other less harmful issues tied to the incident.

After other major fatal incidents in war zones, most nations soon recognized their culpability and made efforts to mitigate the fallout:

- More than eight decades ago, Japan apologized to the United States and paid compensation for the bombing of the Navy patrol boat Panay, which was attacked on the Yangtze River on Dec. 12, 1937. Three men on board were killed and 43 sailors and five civilian passengers were wounded. Japan avoided immediate conflict with the United States, unlike Spain after the destruction of the battleship Maine in Havana Harbor in early 1898. In 1974, however, Adm. Hyman G. Rickover asked researchers to take a second look at Maine’s destruction, sifting through the evidence to determine what happened. They concluded “without a doubt" that it sank after suffering an internal explosion. Later computer modeling, however, determined that an enemy mine could not be ruled out.

- In 1967, Israel attacked the U.S. intelligence ship Liberty after erroneously concluding it was an Egyptian destroyer bombarding Israeli troops ashore during the Six Day war. Thirty-four U.S. sailors were killed and 171 crewmen wounded. The ship became a constructive total loss. There was no doubt about Israel’s culpability for what it soon described as a “tragic mistake." Israel apologized and ultimately paid compensation to the wounded, the U.S. government and the estates of the dead.

- In 1988, the guided-missile cruiser Vincennes shot down Iran Airbus Flight 655, killing all 290 on board. The U.S. soon acknowledged its fault, based on the video of the descending wreck of the Airbus near the ship. After commencement of proceedings in the International Court of Justice, U.S. officials paid compensation to the survivors of those lost and to the government of Iran for the destruction of its aircraft.

In each of these three significant cases involving the United States, immediate further hostilities were avoided, in large measure due to the prompt acknowledgement of fault.

Iran possesses information that would help establish that the incident either was a tragic mistake or one of the grievous alternatives — namely that Iran intentionally targeted and destroyed an innocent civilian aircraft which had just taken off from its own capital’s airport on an international flight.

Iranian authorities knew or should have known about the scheduled flight and should have avoided any risk of damage to the aircraft and passengers as they apparently did in the case nine prior commercial flights that had departed the same airport before the fatal incident.

It remains unclear which Iranian officer was given the authority to authorize missiles to be fired on a commercial flight near an international airport.

But one can contrast this person’s conduct with that of Vasili Arkhipov, the Soviet submarine officer who prevented a nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis by choosing not to follow blindly an order to launch nuclear weapons at U.S. forces.

Iran’s admission of culpability, denial of intent

Iran’s armed forces now say that they unintentionally targeted the passenger plane. Iranian officials have attributed the crash to radar activity and fear of U.S. action.

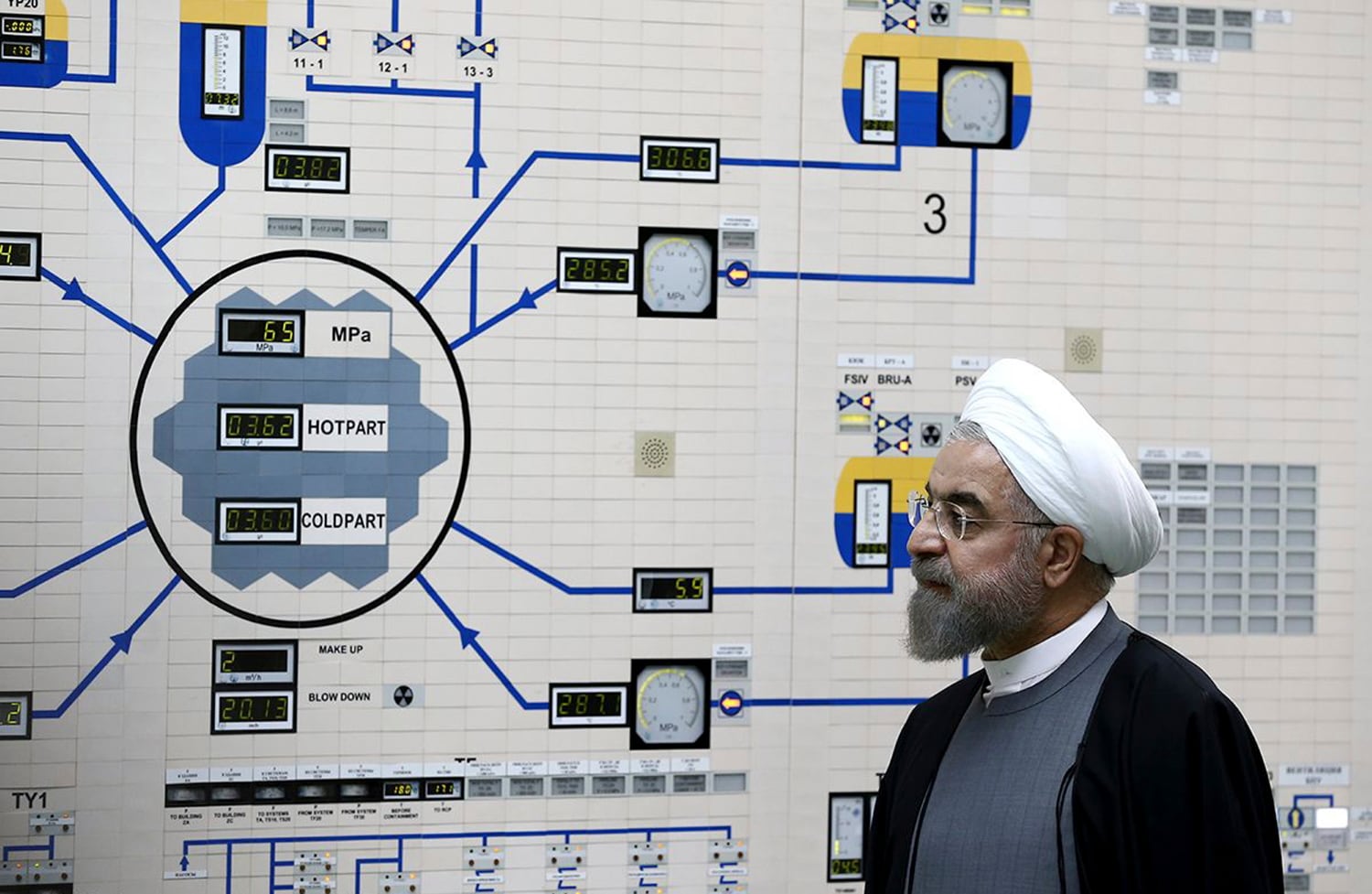

“The Islamic Republic of Iran deeply regrets this disastrous mistake. My thoughts and prayers go to all the mourning families,” said Iranian President Hassan Rouhani.

Iran denied intent to cause the deaths and the jet’s destruction in a statement that claimed the airliner flew "close to a sensitive IRGC military center at an altitude and flight condition that resembled hostile targeting.

"Under these circumstances, the aircraft was unintentionally hit, which unfortunately resulted in death of the many Iranian and foreign nationals.”

Iran’s contention fails to consider the undisputed fact that multiple prior flights departed from the same installation and they followed nearly identical flight profiles preceding the shootdown.

Moreover, Iran admitted that it targeted and intentionally launched the pair of missiles which destroyed the ascending aircraft.

Furthermore, the fatal attack came soon after an intentional Iranian ballistic missile attack on U.S. personnel inside bases in Iraq.

Not surprisingly, U.S. military flights around Iranian borders increased and Iranian military officials reported seeing aerial targets coming toward strategic centers, according to a statement by Iranian armed forces headquarters.

“Human error at time of crisis caused by U.S. adventurism led to disaster,” Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif later tweeted in an attempt to share the blame.

Did Iran really mistake a passenger jet for a cruise missile?

Hours after the first report of Iranians admission that it intentionally fired missiles which destroyed the Ukrainian jet, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps Aerospace Division’s commander accepted personal responsibility for the fatal attack, according to Iranian state TV.

Subsequently, he announced that the commercial aircraft had been misidentified as a cruise missile, and was shot down with a short-range missile that exploded near the plane.

The same media reports noted that the IRGC Aerospace Commander, Amirali Hajizadeh, gave more details during a televised address about the sequence of events that he claimed led up to the disaster.

But the Ukrainian International Air flight should not have been misidentified as an inbound cruise missile because of multiple undisputed factors showing that it obviously was a passenger jet. No one can deny that the airliner was:

• just departing from Tehran Imam Khomeini International Airport on a scheduled flight that had been delayed about one hour;

• squawking electronic signals which identified the aircraft and made known its commercial identity;

• in radio communications with Iranian Air Traffic Control;

• ascending near the airport while seeking its course after takeoff;

• flying at a relative modest speed after rotation (take off);

• not at terminal speed as expected in the case of a cruise missile approaching a target;

• not descending, again as expected in the case of a cruise missile approaching a target;

• “painted” (seen by Iranian radars) and not in a stealthy mode.

• not at the cruising speed of a U.S. cruise missile, most of which reportedly travel about 477 knots; and,

• preceded by nine other aircraft that took off after Iran’s missile strikes on bases in Iraq.

Stated differently, there is overwhelming evidence that the Ukrainian Air Boeing 737-800 should have been properly identified as a commercial passenger jet flying to Ukraine.

It was on a lawful route, authorized by Iran, in Iranian airspace and bound for a disclosed international destination.

Any one of the factors noted above was sufficient to warn competent commanders and those manning the control systems that they were not targeting an inbound cruise missile.

Together, these unquestionable facts removed any reasonable doubt that a competent military command system that controlled sophisticated air-to-ground missiles could have inadvertently mistaken the jet and then intentionally launched the fatal missiles.

Simply stated, the additional contention by the commander of IRGC’s Aerospace Division is self-serving and presents multiple questions of competency and credibility.

The only cause of the airliner’s destruction was military action

The undisputed evidence, now acknowledged by Tehran, is that Iranian military action alone caused the death of 82 Iranians, 63 Canadians, 11 Ukrainians, 10 Swedes, four Afghans, three Germans and three British nationals and destroyed an expensive jet.

A Saturday statement released by the office of Iranian leader Rouhani promised that those responsible for the disaster will be prosecuted.

Tehran also pledged to identify the causes of the mishap and “adopt the required arrangements and measures to address the weaknesses of the country’s defense systems to make sure such a disaster is never repeated.”

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky called on Iran to provide a “full admission of guilt" while also demanding a full and open investigation, the return of the bodies of the dead, payment of compensation to the grieving families and the issuing of a series of official apologies through diplomatic channels.

Some might be inclined to accept the implicit Iranian argument that an admission of culpability with a general denial of intent should end the inquiry.

But Iran’s announced intent to investigate the mishap and prosecute those responsible for it isn’t enough.

For example, it’s unclear if Iran will take the salutary additional steps requested by Ukraine, actions that other nations have taken after similar tragedies.

There should be a wide-ranging international inquiry with its primary purpose to avoid future unintended destruction of commercial passenger aircraft flying over or near danger zones.

This should be addressed by public proceedings with transparent and open hearings.

Why it’s important to determine if Iran intentionally shot down the aircraft

Iran likely will seek to avoid addressing the issues of institutional failures and instead focus on individual culpability.

Just blaming individuals who were involved in the decision to launch the missiles fails to address multiple institutional shortcomings.

Tehran knew or should have known that the natural defensive response to multiple Iranian ballistic missile attacks on targets within Iraq would be for the U.S. to launch more flights around Iran’s borders or to approach the nation’s strategic centers.

Despite this natural reaction by any nation that has its troops attacked, it should be noted that there is no evidence that U.S. manned or drone aircraft attacked any Iranian targets during or after Tehran fired missiles at American personnel in Iraq.

The institutional failures of Iran begin its inability to adhere to strict Rules of Engagement (ROE).

Iran fallaciously claims that “the aircraft was unintentionally hit, which unfortunately resulted in death of the many Iranian and foreign nationals.”

This is a sophisticated attempt to elide culpability. It concedes that Iranian personnel launched the weapons that destroyed a civilian airliner but argues cynically that the missiles did not intend to destroy the aircraft and kill all of its passengers.

Was there even an attempt to identify the aircraft Iranian forces destroyed as a friend or foe?

Who was responsible for failing to protect the aircraft and passengers by communicating its identity to all with “hands on the triggers” as the aircraft departed an international airport?

Who failed to implement a robust ROE that prohibited attacks on unidentified targets?

One of the most important lessons learned from the Vincennes tragedy was the failure by the U.S. Navy to make visual identification of an aircraft before missiles were launched.

A proper Navy investigation that was released to the public ruled out the intentional destruction of a civilian airliner, but at this moment we do not know whether the Ukrainian jet’s passengers died due to a tragic error or if there was an intentional decision by Iranian authorities to cause the destruction.

A real probe into the Iran missile strike might be a complicated enterprise but it should involve multiple nation states, international entities and investigative agencies.

Iran’s drive to become a nuclear power

Even if the Iranian attack proves to be unintentional, the currently known facts establish that Iran has improper ROE and egregiously inadequate Command, Control, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance Reconnaissance Systems (C4ISTAR).

A commercial passenger jet on a scheduled flight had departed a major international airport in a large city. It had traveled only a short distance solely through Iranian airspace. It was destroyed by multiple Iranian missiles that were launched by Iran’s armed forces pursuant to rules of engagement written and promulgated by Iran and the target was chosen based on Iran’s C4ISTAR systems.

The multiple causative failures conceded in Tehran’s latest admissions demonstrate that Iran lacks the capabilities and systems necessary to possess nuclear weapons.

Whatever arguments might have existed before now for allowing Iran to become a nuclear power, there’s no reasonable way to rationalize them today.

Given the institutional failures that led to destroying a civilian aircraft, it’s highly doubtful anyone can make the case that Iran can be trusted to safeguard nuclear weapons.

Misusing those weapons could have a devastating effect on many nations in the region and also would invite apocalyptic retribution on Iran.

This moment creates a compelling reason for Iran to abandon the pursuit of nuclear weapons for its own good.

What must come next

Nations that possess anti-aircraft weapons systems should join with airlines to take immediate steps to reduce the risk to commercial aviation in danger zones.

First, it is imperative to recognize that unintended errors are inevitable during battle.

As I stated on “CBS This Morning” on Friday, there is “no absolute precision when things happen in combat.”

Moreover, I noted, when hostilities loom it is essential to provide warnings to each aircraft and “aircraft must be compelled to avoid danger zones.”

Declared war risk zones and other warnings from specialized insurers should be monitored and communicated to the operators of ships and aircraft and to military officials.

This may require a cordon sanitaire — a total exclusion zone — prohibiting aircraft, particularly passenger aircraft, from entering potential combat zones where there could be risk of intentional or accidental hostile action.

The United States prudently prohibited U.S. commercial aircraft from flying over Iranian airspace prior to this incident.

Destroying evidence

What also seems probable now is that Iran took steps to obfuscate what really happened shortly after its missiles destroyed the airliner.

A contemporaneous video of the missiles impact on the jet, reportedly filmed near the international airport, recorded flashes consistent with missile impacts and the subsequent explosion of an aircraft in flight,

Photographs and videos of the impact zone also included debris that seemed to be part of a Russian-manufactured surface-to-air missile used by Iran.

But within days of the airliner’s destruction, Iran began to “sweep” the impact zones before investigators could conduct proper analysis and even before the remains of the victims could be identified and recovered.

In addition to extensive investigations it is probable that litigation will arise as the result of the deaths and the loss of the aircraft.

The concept of “spoliation of evidence” is generally recognized as the improper destruction or alteration of physical evidence without affording all concerned parties the opportunity to view and inspect it.

The rush to remove evidence and alter the crash site is inexplicable and might suggest that Iran is trying to hide harmful evidence.

But that fits with a regime that chose to avoid sharing primary source evidence about the tragedy and instead tried to substantiate its initial denials by shifting blame and the burden of investigation to other nations.

Iran remains the best source of information, particularly about its intent or lack of intent to strike a commercial airliner when it launched the missiles.

It’s time for it to come clean about all of that. And if Tehran doesn’t, an international panel should do it for them.

RELATED

A retired Navy Judge Advocate General’s Corps captain, Lawrence B. Brennan is an adjunct professor of Admiralty and International Maritime Law at Fordham Law School. He has litigated and investigated many ship collision and casualty cases both for the Navy and in private practice. He was a federal litigator for the U.S. Department of Justice. But what a lot of people don’t know is that he also was the attorney on board the aircraft carrier Nimitz when it launched eight helicopters as part of the Iranian hostage rescue mission on 24 April 1980. He was counsel for the Navy’s probe into the fatal crash on board Nimitz that sparked the service’s “zero tolerance” policy for drugs. He spent more than three decades implementing, drafting and teaching the Rules of Engagement, too. His words do not necessarily reflect those of Navy Times or its staffers.