Gen. Qassem Soleimani, who promoted the religious and political influence of the Iranian regime across the Middle East with covert military operations, was an important figure in the Iranian government.

But that’s not the only reason his targeted killing by the United States has elicited explosive grief and outrage in Iran.

Soleimani’s killing is also roiling Iran – including some people who don’t necessarily follow military affairs – for religious and cultural reasons related to the country’s Shii Muslim history.

Veneration of martyrdom

Islam, the world’s second largest religion, has two main denominations: the Sunnis and the Shiites. Iran is about 95 percent Shiite.

While these two branches have the same basic beliefs, they differ somewhat in their interpretation of the Quran and whether imams are seen as divinely guided leaders.

Nonetheless, as I teach the students in my courses on Islam and politics, the main conflict between the Sunnis and Shiites is a political one.

A power struggle between the two sects have long created tensions in the Middle East. Today, it plays out in a growing competition between the Sunni kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Shii-majority Iran and Iraq.

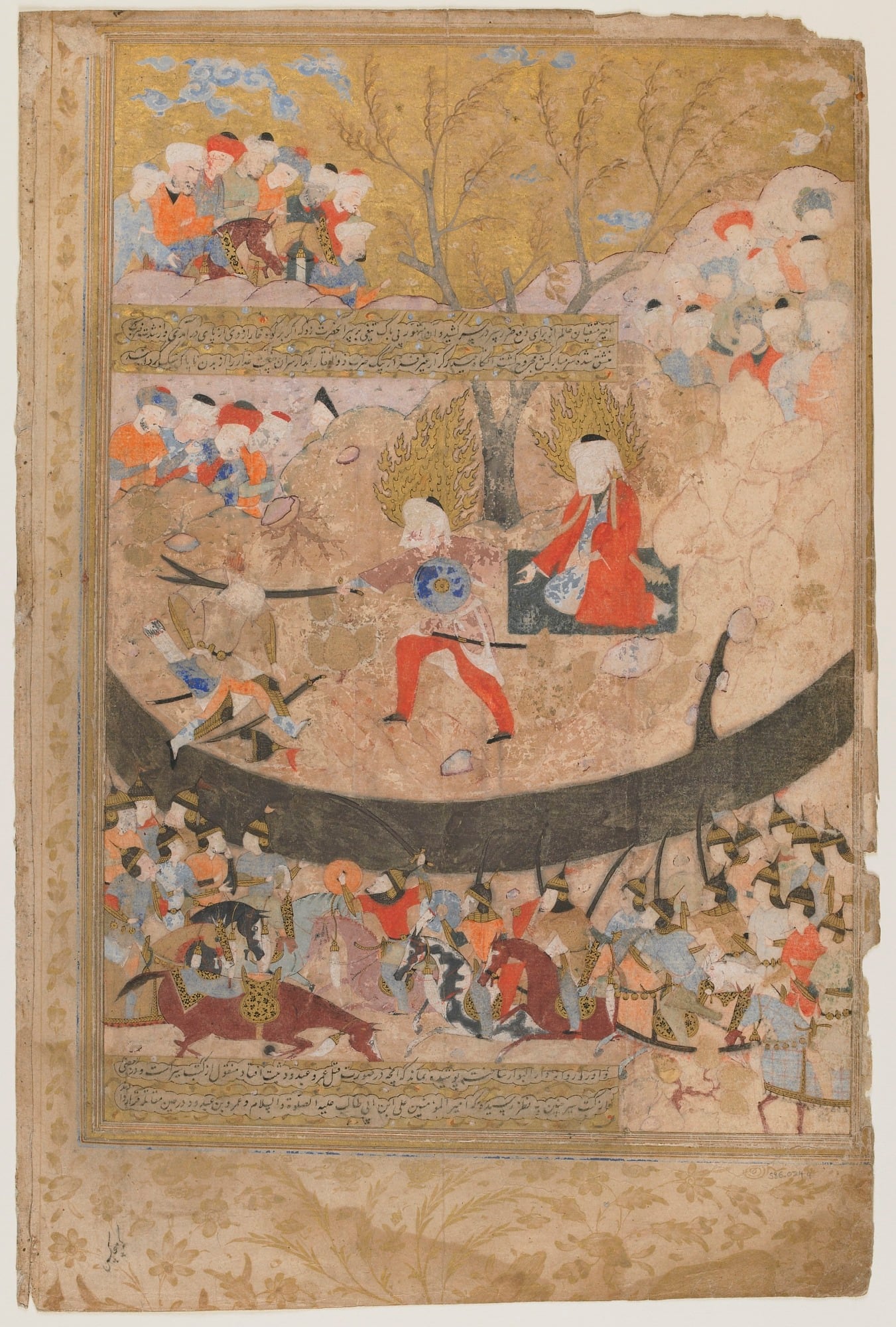

Most relevant to the killing of Soleimani – but absent from most analysis of Iran’s response to the United States’ military action – is that Shiism as a separate sect was born of political assassinations.

Following the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 A.D., in Medina, one group believed that leadership of the community should go to Abu Bakr, Muhammad’s father-in-law, a trusted friend and one of the first converts in Islam.

A second group disagreed: They wanted Muhammad’s cousin Ali to become caliph, or leader. This group became known as Shi’at-‘Ali – partisans of Ali – or “Shi'a.”

Eventually, Ali did assume leadership of the Muslim community, becoming Islam’s fourth caliph. Four years later, he was murdered by his political rivals. Because Ali had agreed to arbitration to resolve Shiite differences about the future direction of the Muslim community, followers saw his assassination as an act of high treason.

Ali was succeeded by his two sons Hasan, who was later poisoned, and Hussein, who was also murdered. Hussein’s martyrdom is remembered each year on the Shiite Muslim holiday of Ashura.

So when a prominent leader like Soleimani – who joined the Iranian Revolutionary Guard at age 24 after Iran’s 1979 revolution, expanding Shiite influence across the Middle East for four decades – is killed in a targeted attack, the death necessarily recalls this dark history of assassinations in the Shiite culture.

Extreme and cruel injustice

Another element of Shiite historical memory relevant to Soleimani’s killing is the concept of extreme injustice, or “zulm.”

Zulm is an Arabic word that in Shii Islam may be used to describe everything from a false accusation to government tyranny.

According to the Shiite scholar Ayatullah Dastaghaib Shirazi, zulm refers to “various kinds of oppressions [that] include insulting, abusing, degrading or imprisoning a person.”

Shirazi, who was imprisoned by the shah of Iran several times for preaching against his rule, before the 1979 revolution, was intimately familiar with this form of zulm.

“Another form of oppression is to usurp someone’s property,” Shirazi writes in his book “Greater Sins”, or “to forcefully occupy a position reserved for someone else.”

This is the “supreme injustice” committed against Muhammed’s cousin Ali, his sons and their descendants, Shiites believe. Their right to lead Islam was repeatedly usurped.

Because Soleimani’s death is widely seen by Iranians to have been unprovoked, it is likely to evoke memories of extreme injustices past.

Soleimani had run military operations targeting Americans, but the Trump administration has offered no evidence that he presented a direct threat to the United States when he was killed.

Acute awareness of injustice is a defining feature of the Shiite faith, according to the Columbia University professor Hamid Dabashi.

Millions of Iranians have turned out to mourn Soleimani in recent days, calling him a martyr and vowing revenge for his killing.

Unity in dissent

Such public support for the government is not necessarily common these days in Iran.

Mass youth-led protests in 2018 and 2019 demonstrated a clear backlash against the regime of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. When the government cracked down on dissent in November 2019, Soleimani himself was in charge of the Revolutionary Guard forces that killed up to 1,500 protesters.

But when the Iranian people agree that an extreme injustice has occurred, history shows, they can become powerfully united in opposition to it. Several scholars point to the 1979 Iranian Revolution as an example of an uprising inspired by zulm.

By the late 1970s, the Shah of Iran was abusing his absolute power both politically and economically to create a huge gap between the ruling elite and the Iranian people. Iranians understood these actions as tyranny, Dabashi argues.

When they rose up in revolt, overthrowing the monarchy to establish an Islamic republic, Dabashi says, Iranians were invoking “qiyam” – meaning to rise in one’s defense. Zulm and qiyam are “thematically related in the moral universe of Shi’i political culture,” he writes in his 2011 book “Shiism: A Religion of Protest.”

Those who died in the revolution are considered martyrs.

The Iranian Revolution succeeded not because “all Iranians thought the same way,” according to the late British academic Michael Axworthy, “but because for a brief time a large majority, despite differences between the social and ideological groups to which they belonged, came together.”

Today, the religious and cultural symbolism of Soleimani’s killing appears to have inspired Iranians once again to set aside their differences, at least temporarily, to mourn a new martyr.

RELATED

Dr. Deina Abdelkader is an associate professor in Political Science at the University of Massachusetts Lowell and an important Islamic legal scholar. She is the author of Social Justice in Islam (2000) and Islamic Activists: The Anti-Enlightenment Democrats (2011), and a co-editor and author of Islam and International Relations: Contributions to Theory and Practice (2016).

Navy Times editor’s note: While this is an explainer, not an op-ed, we take issue with one sentence in this article: “Soleimani had run military operations targeting Americans, but the Trump administration has offered no evidence that he presented a direct threat to the United States when he was killed.” It isn’t apparent that the White House based its decision to kill the general on whether he presented a “direct threat” to the United States but rather has argued, in different ways, that he was a threat to Americans in the region, especially diplomats and members of the armed forces, with some, including the president, suggesting that he posed an “imminent threat” to our embassies. We don’t know if those members of the administration are accurate but we also can’t say that they’re not, short of the intelligence behind the operation being provided to the public.