A future U.S. Navy aircraft carrier will be named Doris Miller, the first African American sailor to receive the Navy Cross for heroism during the Dec. 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.

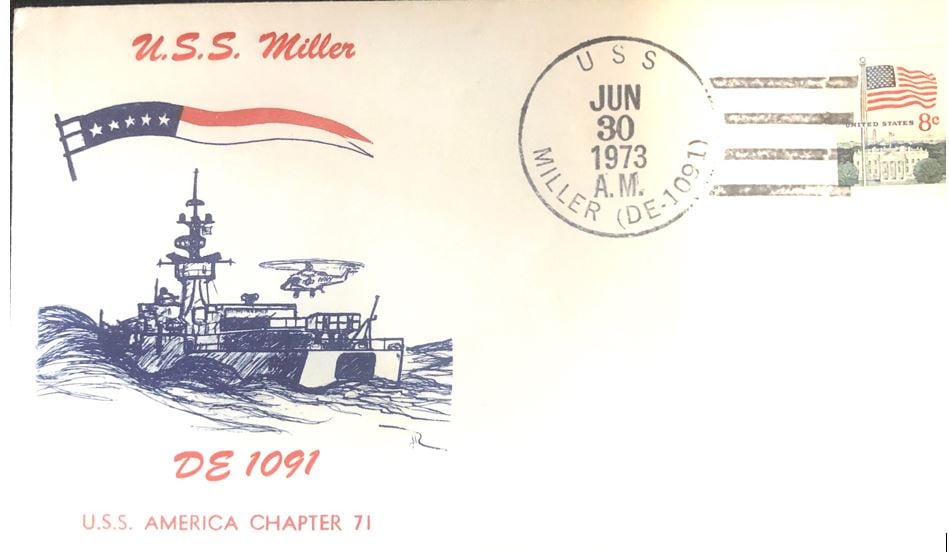

It’s not the first warship to honor the warrior cook. On June 30, 1973, the Knox-class destroyer escort Miller was commissioned.

Two years later, the warship was reclassified as a frigate and served through the Cold War, a constant reminder to the fleet of his heroism.

But the Martin Luther King Jr. Day announcement by Acting Navy Secretary Thomas Modly designating an aircraft carrier that will bear his name is truly unique.

Of the 23 men for whom carriers have been named, he’s the first to have served as an enlisted sailor, the first African American, the first to have received the Navy Cross, the first to earn a battleship heavyweight boxing title and the first to have been killed in action.

Most likely, he’s also the first African American to enter combat in World War II, when he manned a .50 caliber machine gun on board the battleship West Virginia to fire at attacking Japanese planes.

Extraordinary courage

During the sneak attack, he also carried the warship’s mortally wounded commanding officer, Capt. Mervyn Bennion, to an aid station, fought blazes that erupted on board the vessel, toted other sailors to safety and was one of the last three men to leave the West Virginia after the order was given to abandon ship.

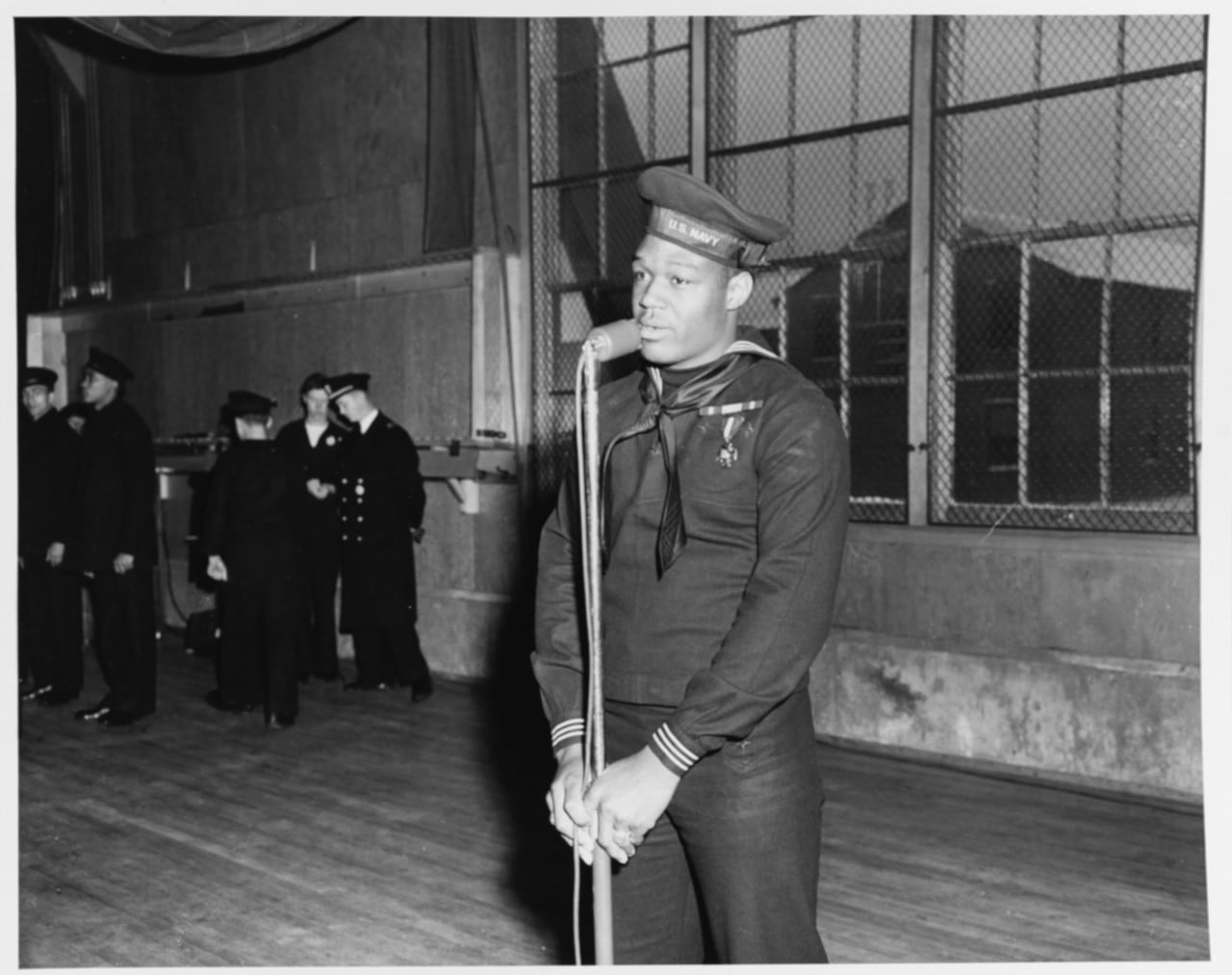

Bennion was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. On May 27, 1942, Miller received his Navy Cross on board the aircraft carrier Enterprise from a fellow Texan, Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, the Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

Enterprise was briefly in Pearl Harbor after returning from the Doolittle Raid and before departing for the crucial Battle of Midway, which destroyed four Japanese carriers and changed the course of the war in the Pacific Ocean.

His Navy Cross citation reads:

For distinguished devotion to duty, extraordinary courage and disregard for his own personal safety during the attack on the Fleet in Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii, by Japanese forces on December 7, 1941. While at the side of his Captain on the bridge, Miller, despite enemy strafing and bombing and in the face of a serious fire, assisted in moving his Captain, who had been mortally wounded, to a place of greater safety, and later manned and operated a machine gun directed at enemy Japanese attacking aircraft until ordered to leave the bridge.

Miller used more direct language to describe that terrible day.

“It wasn’t hard,” he said. “I just pulled the trigger and she worked fine. I had watched the others with these guns. I guess I fired her for about fifteen minutes. I think I got one of those…planes. They were diving pretty close to us.”

As for Adm. Nimitz, a carrier that was first in its class also bears his name.

Humble origins

Doris “Dorie” Miller was born in Waco on Oct. 12, 1919.

As a child, he worked on his father’s farm. A gifted athlete who dreamed of finishing high school, his family’s poverty forced him to drop out of classes and seek employment in town.

"We were a little hungry in those days,” his mother later explained.

He struggled to find work in segregated Waco and in 1939 the 19-year-old enlisted in the Navy as a mess attendant third class, the only rating open to African American recruits.

After graduating Naval Training Station Norfolk, he was briefly assigned to the ammunition ship Pyro. On Jan. 2, 1940, he was transferred to the battleship West Virginia, where he bludgeoned his way to the vessel’s heavyweight boxing title.

That July, he reported temporarily to the battleship Nevada for Secondary Battery Gunnery School and then returned to West Virginia.

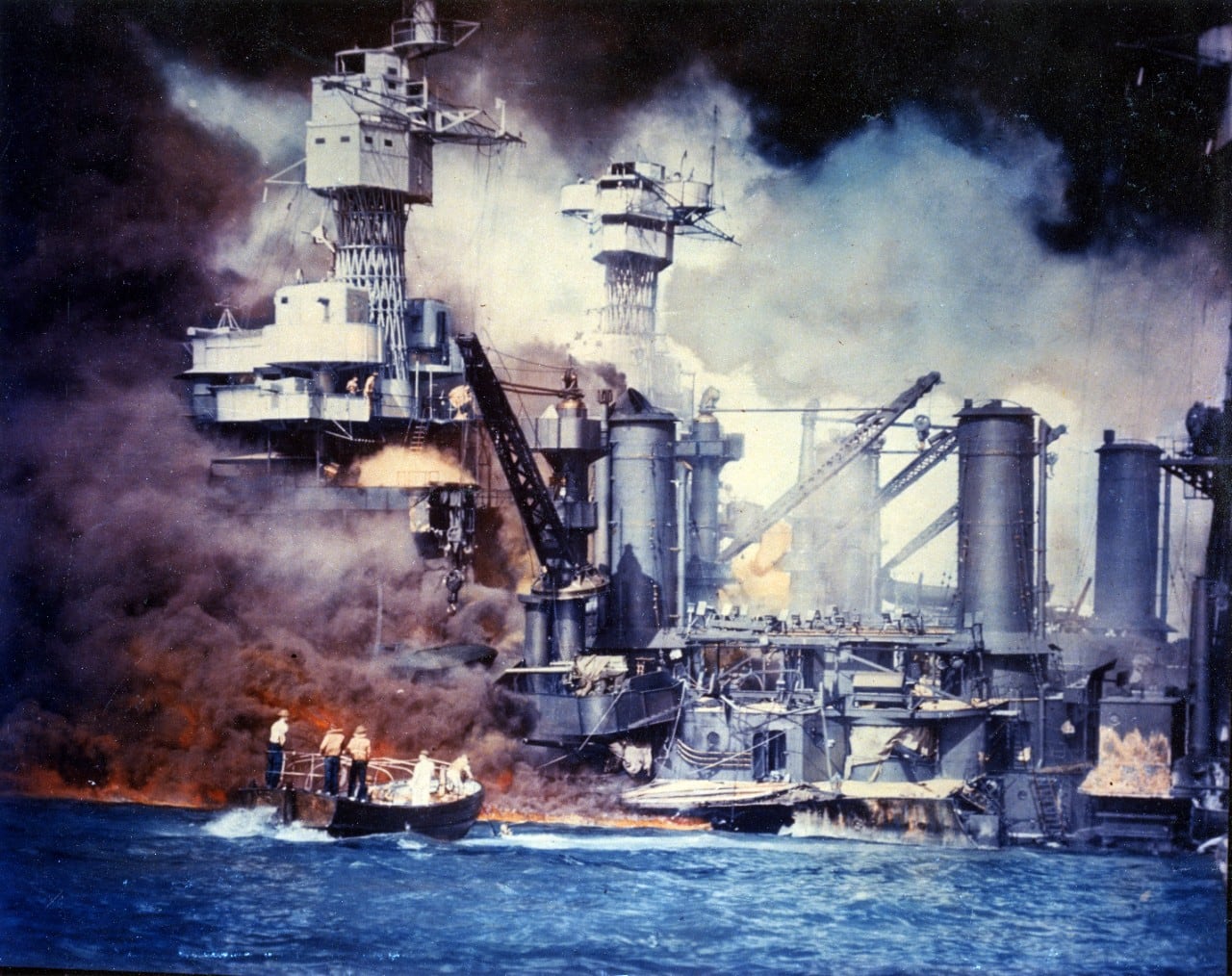

It was moored on battleship row when the surprise attack by Japanese aircraft began. They lanced the battleship’s port side with seven torpedoes and smacked the vessel with two armor-piercing bombs, one of which detonated.

Fuel oil flowing from the nearby burning battleship Arizona snaked around West Virginia and fed fires on board the warship that burned through the night.

Two hard luck warships

Refloated after the disaster, crews extensively rebuilt the entire vessel so that West Virginia could return to the war in 1944.

Within a week of the Japanese raid, however, Miller was reassigned to the ill-fated Portland-class heavy cruiser Indianapolis.

In 1945 it would become the last major American warship lost in combat.

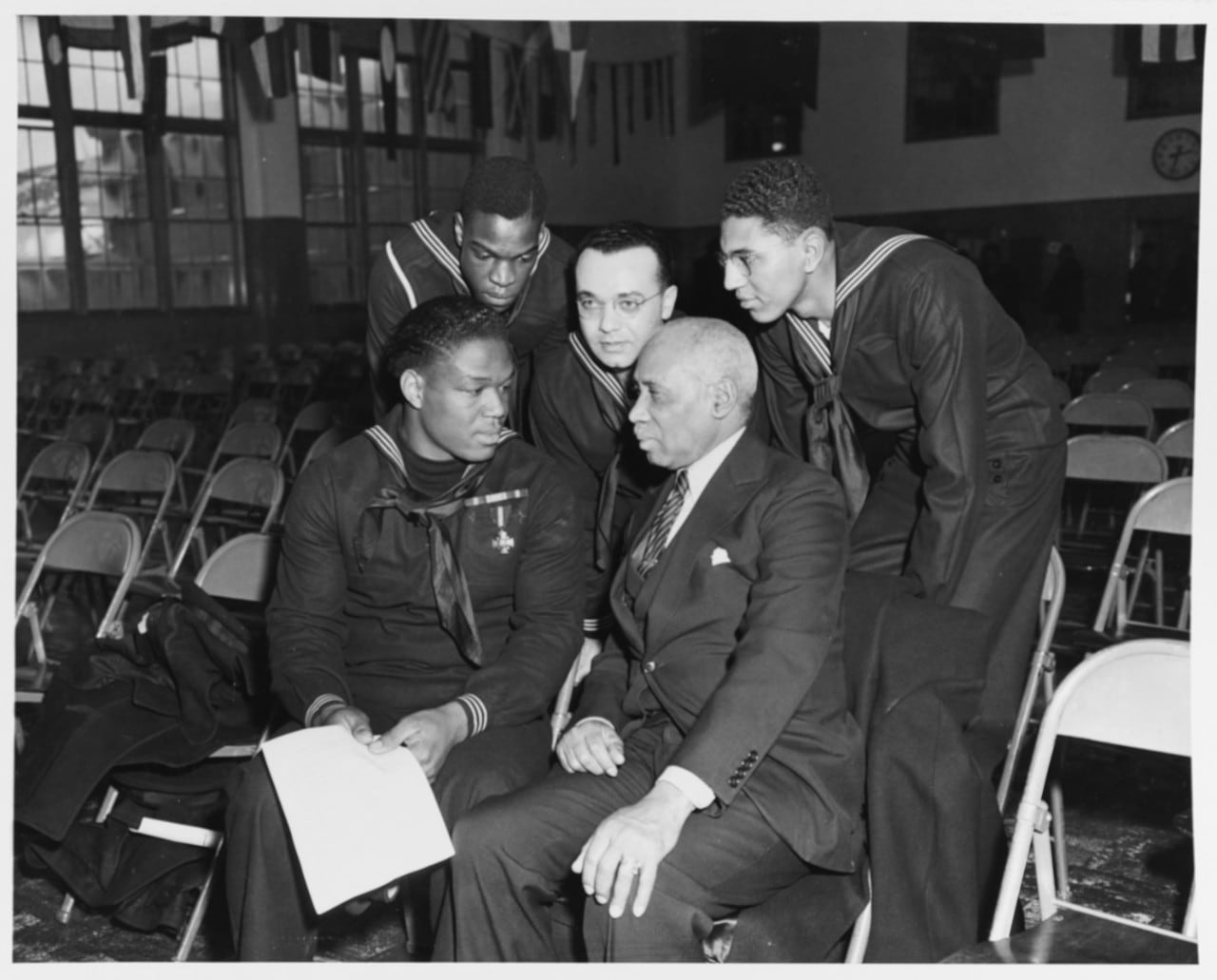

But Miller was destined for another ill-fated warship. He departed Indianapolis when it returned to the mainland in late 1942 and he began a speaking tour to encourage Americans to buy war bonds.

He reported to the newly built Casablanca-class escort carrier Linscome Bay in 1943, which was assigned to provide close air support to soldiers and Marines during Operation Galvanic, the seizure of Makin and Tarawa Atolls in the Gilbert Islands.

At 5:10 a.m. on Nov. 23, 1943, three months after it was commissioned, Liscome Bay was steaming near Butaritari Island when a lone torpedo launched by Japanese submarine I-175 speared the escort carrier near its after engine room.

Liscome Bay’s bomb magazine detonated moments later, spraying shrapnel up to 5,000 yards away. Below the orange mushroom cloud rising from a flattop torn apart, smaller explosions rocked the hulk as ammunition in the antiaircraft guns and planes cooked off.

The carrier sank in 23 minutes, taking 53 officers and 591 crew with it.

One of them was Miller. On Dec. 7, 1943, two years after his heroic morning in Pearl Harbor, he was listed as missing in action.

On Nov. 25, 1944, a year and a day after the carrier went down, that was changed to presumed dead.

How we have named ships

Although some citizens might think that carriers always are named in honor of presidents, that’s actually a relatively new phenomenon.

In fact, there were 41 U.S. Navy carriers before one was named for a president, Franklin D. Roosevelt. In all, 10 presidents have graced 11 carriers, including the unfinished John F. Kennedy, the second flattop to bear his name.

With Miller, I count 23 carriers that have honored people, beginning with the first flattop, Langley, which was renamed after an aviation pioneer after it was converted from a collier.

Like Kennedy, the Navy bestowed his name on two carriers.

The Navy also named carriers after other aviation innovators (Wright paid homage to brothers Orville and Wilbur), an Italian explorer (John Cabot), the first Secretary of Defense (James Forrestal) and lawmakers who played important roles building a modern Navy (Rep. Carl Vinson and Sen. John C. Stennis).

Six decades ago, a Cold War naval rebuilding program — “41 for Freedom” — christened 15 fleet ballistic missile submarines that bore the names of slaveholders, Confederate soldiers or segregationists such as President Woodrow Wilson.

They included the Robert E. Lee and the Stonewall Jackson, which honored the famous Confederate generals.

Today, it’s painful to recall that these boats paid tribute to Confederate leaders during an era marked by the struggle to end racial discrimination, in the Navy and nationwide.

Only one of the 41 subs bore the name of an African American, the agricultural scientist George Washington Carver.

Miller’s moment in Pearl Harbor was long overdue.

A personal postscript

The naming of a future carrier for Doris Miller also gives me great personal joy.

Immediately below is an envelope postmarked on board the destroyer escort Miller on its first day in commission, June 30, 1973.

I sponsored that philatelic naval cover, designed, had it printed and worked with the ship — particularly its postal clerk, who applied crisp strikes of its hand stamp postmark — for the many collectors who obtained this memento.

On Monday, Acting Navy Secretary Thomas Modly summed up what those of us who have been inspired by Doris Miller long believed.

“He died as he lived, an American sailor defending his nation, shoulder to shoulder with his shipmates, until the end," said Modly. "Dorie Miller stood for everything that is good about our nation. His story deserves to be remembered and repeated wherever our people continue to stand the watch today.

“He’s not just the story of one sailor. It is the story of our Navy, of our nation and our ongoing struggle to form — in the words of our Constitution — a more perfect union.”

RELATED

A retired Navy Judge Advocate General’s Corps captain, Lawrence B. Brennan is an adjunct professor of Admiralty and International Maritime Law at Fordham Law School. He has litigated and investigated many ship collision and casualty cases both for the Navy and in private practice. He also was a federal litigator for the U.S. Department of Justice. His views do not necessarily represent those of Navy Times or its staffers.