President Donald Trump has rescinded, reversed or otherwise ended many of former President Barack Obama’s signature policies – but not a prominent one.

When it comes to fighting terrorism, the current commander-in-chief has upheld, and even extended, his predecessor’s linchpin strategy: using U.S. military special operations forces and targeted killings on a grand global scale.

This strategy is highlighted by Trump’s recent orders for the military to kill or capture al-Qaida leader Hamza bin Laden in September 2019 and Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in October 2019 – and in January 2020, for a drone strike to kill Iranian Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani.

The tactic of sending specially trained operatives into hostile territories dates back to America’s Colonial days. In September 1776, Lt. Col. Thomas Knowlton’s Rangers carried out one of the first U.S. reconnaissance missions, identifying enemy positions around what today is Manhattan.

They quickly found themselves engaged in a firefight with the British.

Increasingly called upon

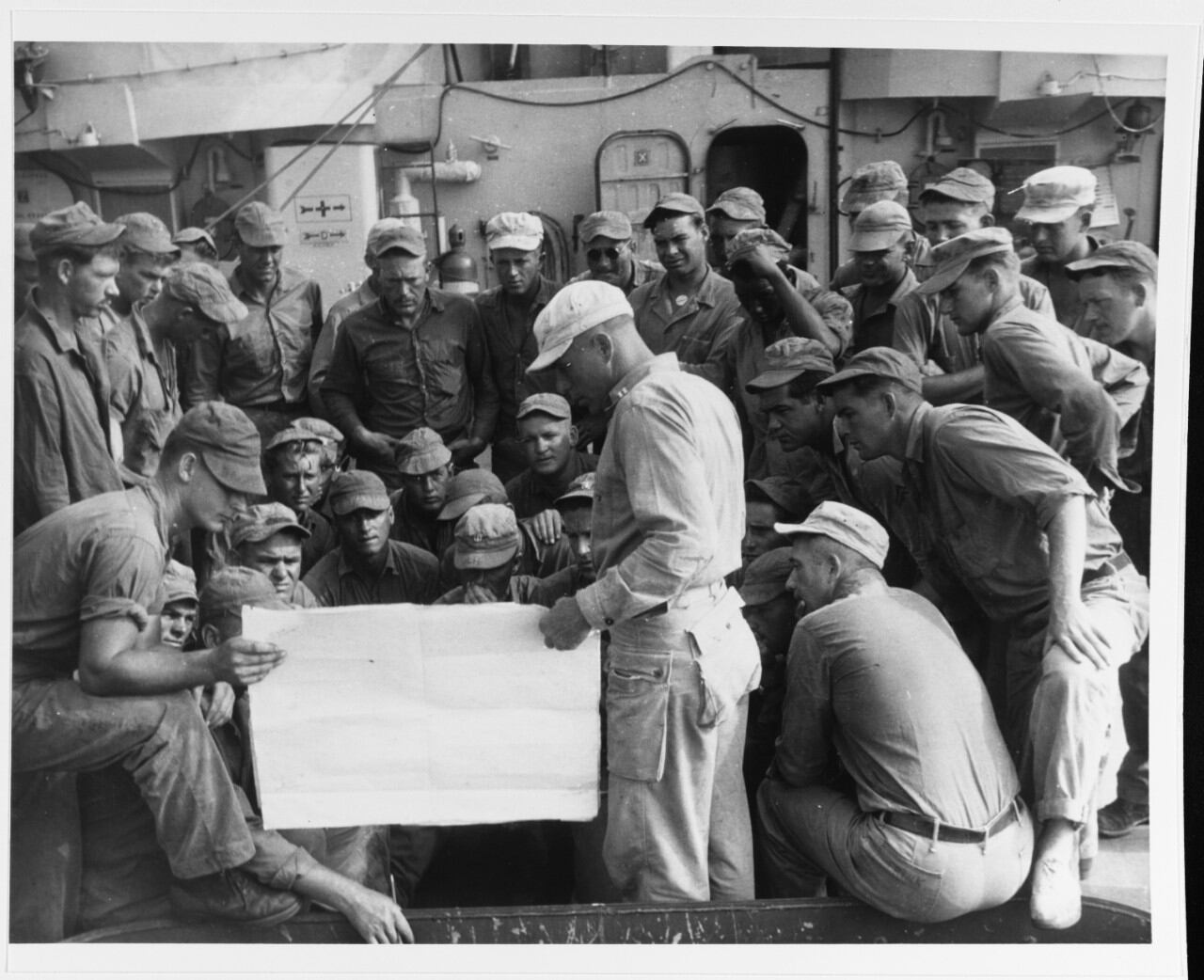

In the mid-20th century, America developed groups of covert combatants, including units that preceded the Navy SEALs, to operate in parallel with larger conventional military forces.

For instance, during the Korean War, U.S. Underwater Demolition Teams accomplished what only specially trained troops could do consistently and effectively – destroying bridges and railroad tunnels.

The rise of international terrorism in the 1970s led President Jimmy Carter to establish the Army’s 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta, better known as Delta Force.

Obama, however, transformed special forces from an auxiliary arm into the tip – and at times, the whole – of America’s counterterrorism spear. He boosted special operations forces by 15,000 troops and support staff, bumped their budget 12 percent to $10.4 billion, and deployed them much farther and wider – more than doubling their geographical footprint from 60 to 135 countries.

Trump has eagerly embraced this strategy, deploying 8,000 special operations personnel to 80 countries. Today, they operate in predictable places such as Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as surprising settings such as South America’s Andes Mountains and Africa’s Sahel region.

It took me 10 years of research to fully grasp Obama and Trump’s shared approach. In 2017, I co-produced “How Special Ops Became Central to the War on Terror” with Retro Report for the New York Times. PBS recently aired a shorter version. I’m also directing “Cojot,” which tells the little-known story of a hostage who played a key role in the first special operations rescue mission in a hostile country – the 1976 Operation Thunderbolt, better known as Israel’s daring Entebbe raid.

My conclusion is that this strategy offers significant benefits, often in terms of speed and competency, but brings along severe risks, as well – such as lack of transparency and accountability, and potentially conflicting national priorities.

Clear advantages

Using a select group of elite troops and choosing very specific targets can be a highly efficient way for presidents to advance military and foreign policy goals that otherwise might take countless years, hundreds of billions of dollars, massive deployments, intense debates with Congress and thorny international entanglements.

Imagine, for instance, if President George W. Bush had simply sent special operations troops to kill Iraqi President Saddam Hussein rather than getting mired in an endless war in that country.

Trump recently offered an example, albeit on a smaller scale, of how this approach works: Shortly after announcing the pullout of U.S. troops from northern Syria, he successfully deployed Delta Force to take out al-Baghdadi.

This strategy is also relatively inexpensive: Special operations spending in the 2020 federal budget amounts to $13.8 billion – an enormous sum that is nevertheless just 1.87 percent of the $738 billion overall defense budget.

And high-profile successes can boost presidents’ public approval ratings. Obama’s climbed from 46 percent to 52 percent after Osama bin Laden’s killing, and Trump’s rose from 41 percent to 45 percent after al-Baghdadi and Soleimani’s deaths.

Using small dedicated groups can also fill gaps in intelligence-gathering left by satellites, drones and technological spying.

Special operations soldiers can track leads on the ground, interrogate suspects and flesh out information needed to make sound decisions and execute complex missions. Zeroing in on specific marks can minimize harm to civilians who might live or work nearby – rather than destroying a village to kill one man, commandos can just attack that individual in his home.

With this approach, the United States uses force more in line with its opponents. Unlike the skyjackers of the 1960s and 1970s, today’s ideological killers do not negotiate.

They tend to be extremists, like religious fanatics or white supremacists, rather than attention-seeking secular political activists. They play by different rules, and so do special operations forces.

Unlike conventional forces, special operators do not have to constantly answer to the public, face media scrutiny or become a political punching bag.

In fact, the American people have rarely demanded to know more about exactly what special operations forces are up to.

Serious drawbacks

One of the problems with the dependence on special operations forces is that it exhausts the very people on whom it relies.

“The force has been stretched to the max,” former Delta Force intelligence officer Wade Ishimoto says in my co-production with Retro Report, “How Special Ops Became Central to the War on Terror.”

“Special operations should not be the panacea for every kind of difficulty,” he continues.

Ishimoto warns that special operations soldiers are bound to burn out because there are too few of them to handle all the assignments in far-flung locations. Indeed, in recent years, they have experienced an increase in alcohol abuse and suicides.

Yet Americans are often in the dark about their special operations. With specialized, clandestine forces, presidents likely find it easier to wage war without consulting Congress and without clear strategic plans.

The recently released Afghanistan Papers show presidents can keep significant secrets about wars, such as the 18-years-and-counting Afghanistan conflict.

The most obvious downside is that special operations missions can fail miserably. In April 1980, when Delta Force tried to rescue the American hostages held in Iran, the troops never made it past their initial rendezvous point in the desert.

In 2017, al-Qaida-affiliated terrorists in Niger ambushed U.S. special forces soldiers, killing four of them.

The enigmatic nature of the operations means it is possible some special forces deaths never make the nightly news or morning papers.

Still, I doubt this strategy will change in any significant way, regardless of who wins the November 2020 presidential election. It’s not just that the benefits outweigh the drawbacks – it’s that, to many people, there is no better alternative.

If there were, Trump would probably be quite happy to scrap yet another Obama policy.

RELATED

Assistant professor Boaz Dvir teaches writing and production in the Department of Journalism at Pennsylvania State University. A former Israel Defense Force officer, his documentaries include “How Special Ops Became Central to the War On Terror” for The New York Times, the short “El País de la Eterna Primavera (Land of the Eternal Spring)” and "Cojot: A Holocaust Survivor Takes History Into His Own Hands.” His views are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Navy Times or its staffers.