"Range, mark!” the commanding officer called.

“Two-five-double- oh,” came the response.

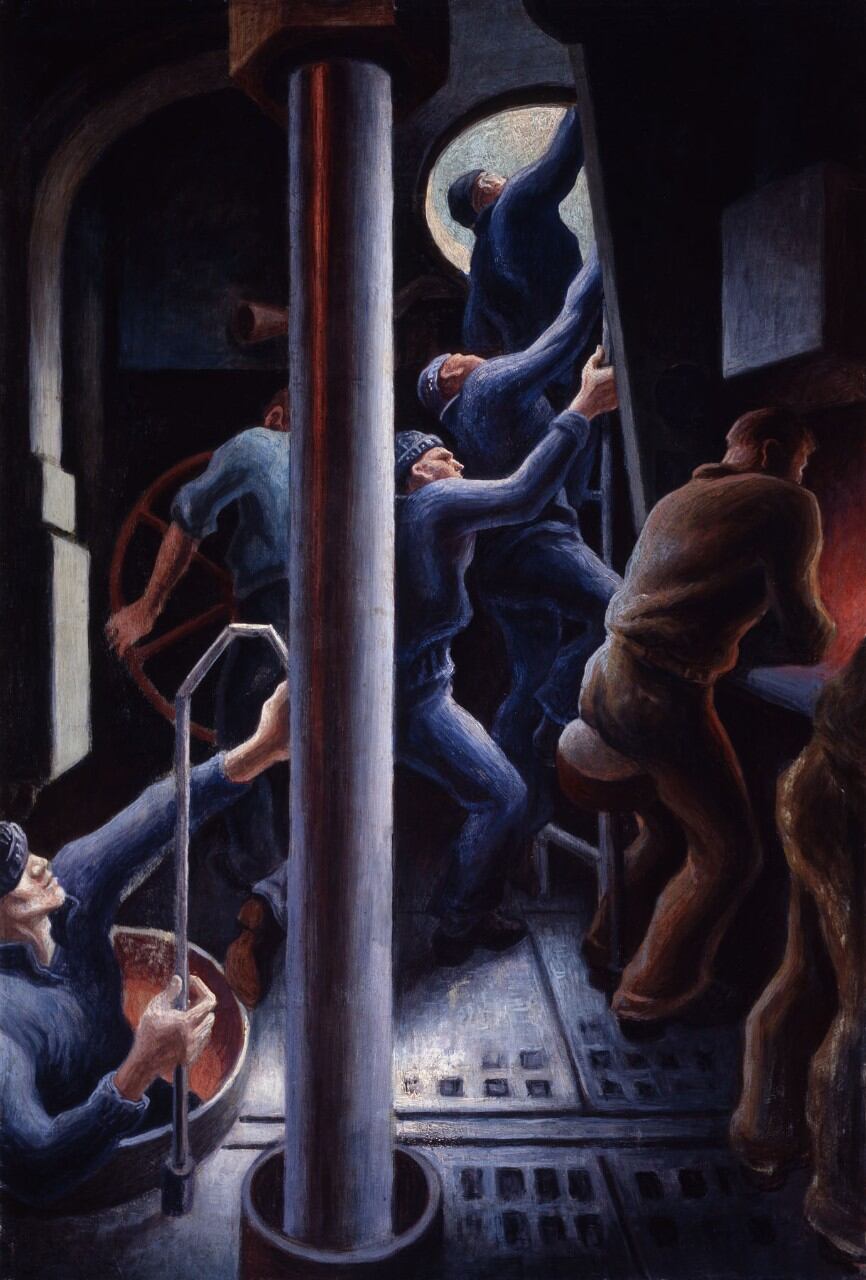

“Make ready the forward tubes,” he ordered next.

“Stand by.”

The tension in the conning tower of the U.S. Navy submarine Shark, already palpable, ratcheted up a notch.

“Fire one!”

Nine seconds later: “Fire two!”

Seven seconds later: “Fire three!”

The command was repeated until all six torpedo tubes in the bow were empty.

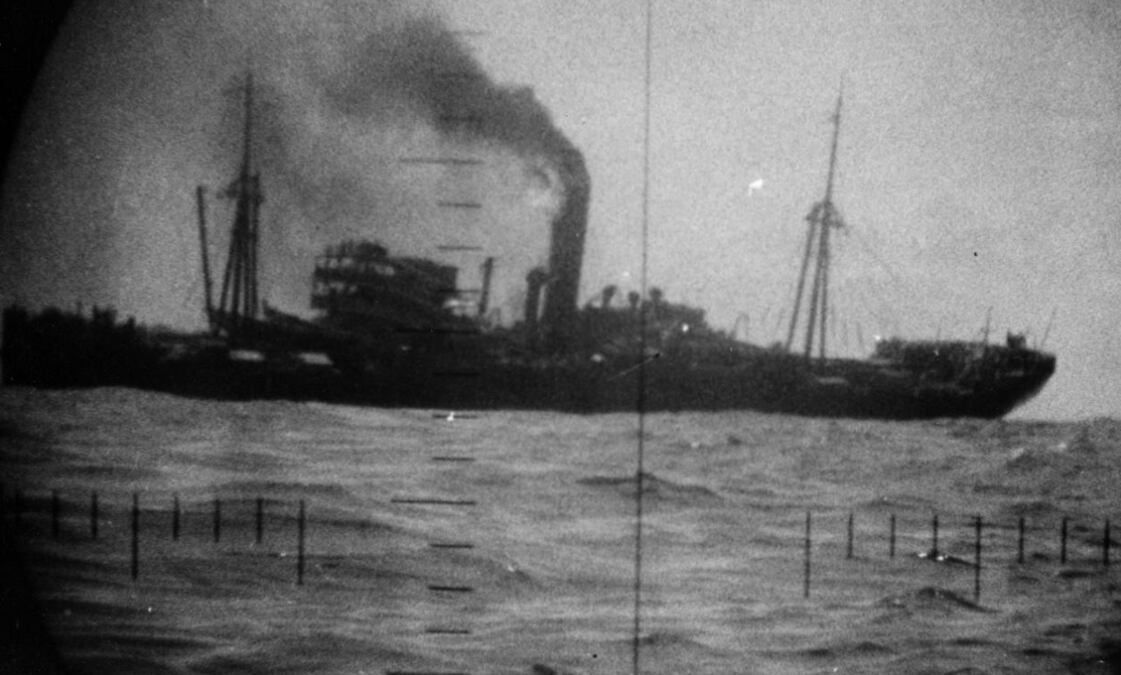

Cmdr. Edward Blakely quickly scanned the horizon, then focused on his quarry, the Japanese troop transport Takaoka Maru, the largest of seven merchantmen in the Saipan-bound convoy.

Eight-one seconds after the first torpedo was launched, Blakely watched it hit the ship, tearing a hole in its aft quarter.

He swung the periscope around to check on the destroyer at the head of the convoy and heard two more torpedoes slam into the Takaoka.

Nine seconds later, the Shark’s crew heard the remaining three hit the leading freighter, the Tamahime Maru.

By the time Blakely looked again at his first target, it had broken in two, taking most of the 3,500 soldiers on board down with it.

“It was unbelievable that a ship could sink so fast,” Blakely said.

Six torpedoes. Six hits.

A few thousand yards away, another submarine, the Pintado, prepared to take its licks at the convoy.

Just after midnight on June 6, 1944 — D-Day in Normandy, half a world away — it lined up a shot on a freighter and fired four stern torpedoes.

All missed the intended target, but hit and heavily damaged another Japanese merchantman.

Later that morning, the Pintado fired its six forward tubes, made six hits, and sank two ships.

In retaliation, five Japanese escorts boxed it in and unleashed 50 depth charges, some very close. But by mid-afternoon the enemy gave up and moved on, leaving the submarine unscathed.

The Shark, the Pintado, and a third boat, the Pilotfish, quickly regrouped and took off after the convoy.

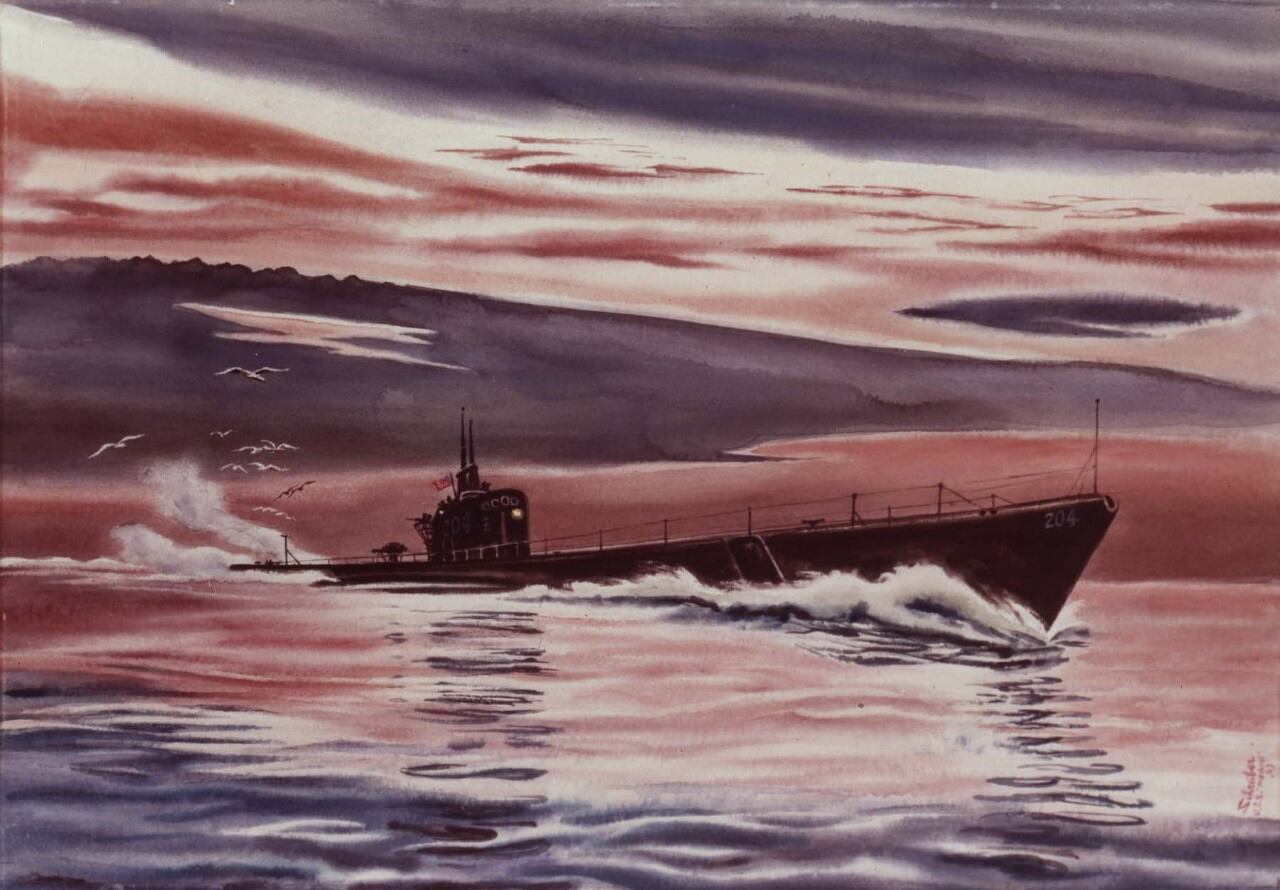

This trio was part of a newly created tactical unit. In official Navy parlance they were a “coordinated attack group.”

But submariners knew them as a wolf pack, and gave this particular combo a name — Blair’s Blasters, after the pack’s officer in command, Capt. Leon Blair.

“Wolf pack” is a term long identified with the German navy, bringing to mind flotillas of U-boats preying on Allied shipping in the Atlantic. But, taking a page from the Nazis’ playbook, the U.S. Navy had by mid-1944 developed its own extremely successful wolf pack program in the Pacific theater.

In the spring of that year Blair’s Blasters was only the sixth group dispatched since an experimental pack had sailed nine months earlier.

In one week of near-constant battling with the enemy, the Blasters would rack up a remarkable record, and demonstrate beyond a shadow of a doubt the effectiveness of America’s group submarine tactics.

The genesis of American wolf pack operations lies in a secret dispatch that Adm. Ernest King, the commander in chief of the United States Fleet, sent to Adm. Chester Nimitz, the commander of the Pacific Fleet, on March 12, 1943.

The memo directed Nimitz to “form a tactical group of 4 to 6 submarines trained and indoctrinated in coordinated action.” King specified that the unit was to be used in the Solomon Islands, where Japanese naval forces were still pummeling the Americans at sea.

Nimitz sent the dispatch to Rear Adm. Charles A. Lockwood, the Pacific Fleet’s submarine commander, for action. Within days, a planning board at Pearl Harbor considered the issue and, recommending essentially no change in current tactics, sent their decision back up the chain to King.

There things might have stayed but for the interest in wolf pack tactics of two senior submariners: Capt. John “Babe” Brown, a famous Navy footballer, and Capt. Charles “Swede” Momsen. The pair approached a somewhat skeptical Rear Adm. Lockwood with a request to develop a coordinated attack doctrine.

Permission granted.

Swede Momsen was a well-known figure in the submarine force. In 1929 he invented the submarine escape device that came to be called the Momsen Lung.

A decade later he directed the raising of the submarine Squalus after it sank off the New Hampshire coast. At Pearl, Momsen was hard at work sorting out the nagging torpedo problems that had plagued American captains since the beginning of the war.

He was a hands-on, think-outside-the-box, let’s-get-it-done kind of guy, bursting with innovative ideas and the energy to bring them to fruition.

When Brown and Momsen embarked on their experiment in June 1943, they chose as their laboratory the dance floor of the bachelor officer quarters at the Pearl Harbor sub base.

The black-and-white-checkered floor, in a lanai at the rear of the building, was 80 feet square. They figured they had a giant game board upon which to assay wolf pack operations, with each square representing 1,000 yards, and asked the base shops to build models of submarines and Japanese ships for gaming use.

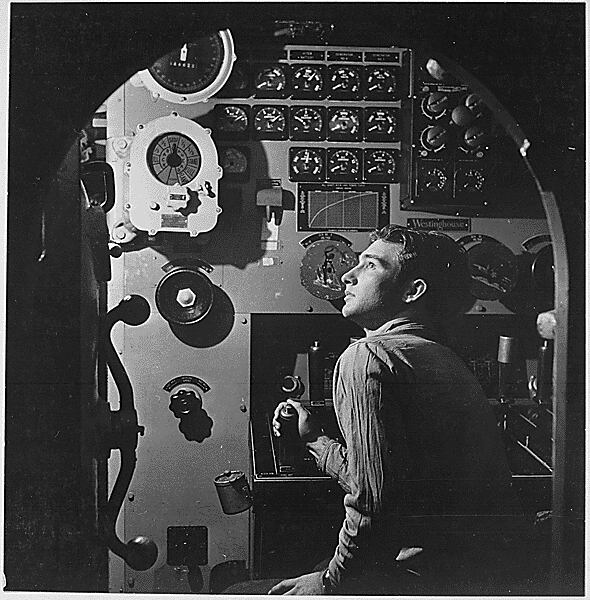

They set up bamboo screens, behind which commanding officers and their firing teams — at Pearl Harbor while their subs were in for refit — could make-believe they were in their conning towers.

Telephones were provided for intership communications. Other officers, experienced in antisubmarine warfare, were brought in to direct the Japanese convoys across the dance floor.

Marine guards were stationed around the lanai to keep the curious at bay, for it must have been a strange sight to see 40 or 50 men playing with toy boats on the checkered floor in the middle of the day in the middle of the war.

In best war game tradition, sailors pushed the enemy ships across the checkered floor at given intervals, in formations directed by their erstwhile commodore.

He would order zigs and zags, speed changes, and shifts in position. The packs, varying from two to eight boats, were given brief glimpses of the model convoys, the skippers peeking around the screens for a three-second look at the developing situation to simulate the view through a periscope at sea.

Under Brown’s and Momsen’s watchful eyes the sub crews employed a variety of coordinated actions to track the convoy and go in for the attack, one square at a time. The two captains would assess the damage, noting the most successful tactics.

The BOQ dance floor was soon dubbed “Convoy College.”

In mid-July 1943 Swede Momsen proposed taking the college to sea so they could experiment with a real convoy and real submarines.

On Aug. 29, the first three-submarine group sailed into Hawaiian waters to “attack” a five-ship eastbound American convoy. Over the course of the night they made five successful mock attacks.

Coordinating the submarines proved difficult, but Momsen optimistically noted in his report to Lockwood that “the convoy could not have survived such a coordinated attack.”

The 17-point doctrine that Brown and Momsen developed over the course of four months had some similarities with the tenets Vice Adm. Karl Dönitz put into practice in September 1940 when he formed the first German U-boat wolf pack, but it was more noteworthy for its differences.

The German wolf packs sometimes numbered a dozen or more U-boats and preyed on convoys of 100 or more ships. When a convoy was sighted, individual U-boats were summoned and controlled from the land-based submarine command headquarters, requiring significant radio traffic in both directions.

Through trial and error, the creators of the American wolf pack doctrine concluded that in the vast expanse of the Pacific, a three-boat pack that departed port together had the best chance of success against Japanese convoys, which rarely exceeded 10 ships.

The Americans’ tactical group formation, intended for making successive attacks, consisted of “flankers” and a “trailer.”

The flankers would cruise parallel to a convoy’s general course, sometimes racing ahead in what was known as an “end around” to position themselves for an attack. The trailer kept track of the convoy and informed its pack mates of course and speed, usually bringing up the rear, but sometimes trailing ahead of the enemy.

The first sub to make contact with a convoy was expected to radio the enemy’s position to the other boats immediately, and then devise an attack.

Once it made the initial attack, that sub became the trailer. The flankers then went on the attack, leaving the trailer free to reload and pick off stragglers.

Brown and Momsen also decided that a division commander should be assigned to one of the submarines as the pack’s officer in tactical command, to quickly distill the information coming in from the pack and control its movements from the immediacy of the battle.

When the first operational wolf pack, composed of the Cero, Shad, and Grayback, departed from Midway on October 1, 1943, to patrol the East China Sea, Momsen himself was on board as its OTC.

The pack was four days into its patrol when Momsen received a dispatch indicating that an enemy convoy was due to pass through 28˚30’N, 138˚10’E — about 500 miles southeast of Yokohama — at about noon on Oct. 10.

Sure enough, late in the afternoon of the 10th, the Grayback sighted smoke to the north. Its captain, the impetuous Lt. Cmdr. John A. Moore, immediately went on the attack. But he failed to first notify the Cero and Shad, as the doctrine specified.

Only one of the four torpedoes he fired hit home, damaging a 6,200-ton cargo ship. And only afterward did Moore attempt to contact his mates — many times over the next 24 hours, to no avail.

The next night the Cero found itself in a similar position. It had picked up the enemy on its radar, but was unable to make radio contact with the rest of the pack. The radios then in use were not suited for short-range transmission, and if a boat was underwater, it couldn’t pick up any kind of signal.

This problem persisted throughout the patrol, but the pack nonetheless succeeded in sinking or damaging 13 ships.

In Momsen’s final report on the mission, he took full responsibility for the failings of the attack group and the lack of coordinated operations. The inability of the submarines to communicate with one another at will was at the top of his list.

It was back to the game board at the BOQ to sort things out.

Lockwood had meanwhile sent out a second wolf pack, which sailed toward the Marianas.

Although communications and coordination were once again bugaboos, the group bagged nine enemy ships over the course of five weeks: five sunk, four damaged.

A third mission, to the west of the Marianas, departed two weeks after the first two packs returned, but had little to show for their efforts.

Although the subs were better coordinated thanks to lessons learned from the first two missions, the results were lackluster. The group made just five attacks and fired only 18 of 72 available torpedoes, sinking only one small freighter and damaging an escort carrier.

Wolf packing then went into hibernation for the remainder of the winter. Babe Brown distilled all the patrol reports and attack results into a revised doctrine, circulated a draft among sub commanders at Pearl Harbor for their comments, and incorporated them into a further revision, which became, on Jan. 18, 1944, the official doctrine.

Pack operations resumed a few days after the spring equinox. But so did the problems.

The first pack sank seven ships, but coordination remained poor.

The second pack’s patrol was a near disaster. Their total bag was a single small gunboat. And they nearly lost one of their wolves, the Perch, to an enemy depth charge.

This wolf packing business didn’t seem to be faring well, or getting any easier.

Then, on May 16, 1944, Blair’s Blasters put to sea.

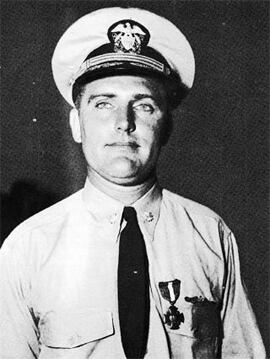

The all-volunteer submarine force has always drawn men of strong and unusual character, and Capt. Leon Blair was no exception. He had joined the Navy after serving in the U.S. Army in World War I.

Managing to secure an appointment to Annapolis, he graduated in 1923 with the nickname “Chief.” He joined the submarine force after three years on surface ships, serving on board the primitive O- and S-class boats before taking command of the Stingray, one of the first of the powerful, long-legged fleet-type submarines.

Finally, after a tour of duty at the sub base in Panama, Blair arrived at Pearl Harbor in mid-1943 to head two submarine divisions.

When he was picked to lead the wolf pack, Chief Blair had never been on a war patrol.

The three boats in his pack were of the strengthened Balao-class boats, outbound on their first war patrols and led by first-time commanding officers: Lt. Cmdr. Bernard “Chick” Clarey on the Pintado, Lt. Cmdr. Robert “Boney” Close on the Pilotfish, and Cmdr. Edward Blakely on the Shark.

First-timers, maybe, but between them they had 15 submarine war patrols under their belts.

The pack had 4,000 miles of ocean to cross before reaching its patrol area west of Saipan, in the Northern Marianas. Its mission was to intercept shipping en route to that island, which was due to be invaded by American forces on June 15.

Before their departure Blair had given each captain a 21-page “Patrol Plan” that covered everything from the latest intelligence on Japanese antisubmarine techniques to specific instructions on group coordination, from daily patrol grids to radio frequency rotations.

On the way, Blair worked his boats hard, drilling their crews every day in group tactics and communications.

On May 29, the Blasters reached their patrol zone, Area 14. This rectangle of the Pacific Ocean encompassed some 90,000 square miles almost due south of Japan, and about 600 miles north of Saipan.

The only dry land in Area 14 was the tiny Bonin Islands, which included Iwo Jima.

Blair turned the officers’ wardroom of the Pintado into his command center. He showed up each day wearing neatly pressed khaki shorts, a regulation short-sleeve shirt, knee-length socks, and spit-polished shoes.

With his cigar tightly clenched in his teeth, he would pore over radio dispatches and ocean charts, while his personal mess attendant kept him well supplied with steaming hot coffee and ice cubes from the pantry.

Blair would drop the cubes in the cup, one at a time until the coffee was cold, before drinking it. (Thinking to save the captain some effort one morning, another steward brought the coffee out already cold. Blair’s resonant excoriation of the poor sailor echoed throughout the boat.)

At Blair’s elbow his yeoman made notes and wrote out orders, the first of which was to disperse the Blasters into a scouting line, each steaming on the same course, separated from the others by 15 miles side to side.

Things were quiet until the dawn of Wednesday, May 31. At 5 a.m. the Pintado received a radio message from Lockwood saying that another American submarine in the area had spotted a Japanese convoy of three freighters and four escorts heading east toward Saipan.

By early evening the Blasters were in hot pursuit. The enemy ships were making only eight knots, but their wild zigzagging made it hard for the wolf pack to get into suitable attack positions.

The Shark tried first, but had to break off its approach.

The Pintado was next up and, at 4:37 a.m. on June 1, fired all six forward torpedoes.

To Chick Clarey’s astonishment, all six hit. Five sank a large freighter, the 10,000- ton Toho Maru, and the sixth damaged the smaller Kinshu Maru, an auspicious kickoff to a remarkable week for Blair’s Blasters.

As the pack continued to track the convoy, a second convoy unexpectedly joined the mix of targets.

The Shark was the first to pick up these new ships: three freighters and two small escorts. The sub was spotted as it tried to maneuver for an approach, dove to evade, and drew 27 depth charges — “none close,” the commanding officer noted.

Two hours later, the Shark surfaced, and recommenced its hunt.

In the meantime, the Pilotfish, which had been entirely out of the fray the night before, received a message reporting yet a third convoy. In best wolf pack practice, Boney Close sent a report to his pack mates, then began the chase.

This convoy was big: seven merchantmen in three columns. Early on Friday, June 2, Blair ordered the Shark and Pintado to join the Pilotfish.

But as the Pintado neared the convoy, the submarine was discovered, and the escort pounded it with 48 depth charges over the next half-hour.

That attack proved advantageous to the Shark, as Ed Blakely homed in on a large transport. It zigged away suddenly, revealing a still-larger ship in the second column.

Late that evening, the Shark fired a spread of four torpedoes. About a minute later the first one hit, followed by two more.

The final torpedo missed the big ship, but hit another freighter. Four for four: pretty good shooting, and great pack coordination.

Blair’s Blasters had been battling the three convoys for 72 hours when, on the afternoon of June 3, the Shark located yet another convoy inbound for Saipan.

Blakely immediately sent a position report to the rest of the pack. For the second time in three days, Blair’s Blasters had two convoys in sight.

The ocean was flush with targets. Blair ordered the Shark and the Pilotfish to track the new arrival, and the Pintado to stay with the third convoy.

The wolf pack’s coordination was improving. Contact reports were swiftly dispatched.

The submariners had discovered they could use their surface search radars to ping a short message. So they wouldn’t be mistaken for an enemy vessel, the submarines kept one another apprised of their own positions.

Blair responded quickly to situational changes, repositioning the boats as needed. When the Pintado was unable to close on the third convoy, for example, Blair ordered it to join its pack mates in pursuit of the fourth. It was all falling into place.

The next day, June 4, Blair ordered his boats to make a “simultaneous” attack.

This tightly coordinated effort would be a first for the Brown-Momsen doctrine. The Pilotfish, trailing ahead of the convoy, would dive and shoot at 4 p.m. Five hours later, the flankers would make their runs. When the conditions for the initial attack improved, Blair moved the Pilotfish’s attack time up two hours.

The Pilotfish was in position as directed when the convoy inexplicably changed its general course, spoiling Boney Close’s shot but driving the enemy right at the Shark.

Blakely tracked the convoy until he had a good, clear shot, then fired four torpedoes at a troop transport, the Katsukawa Maru. He didn’t know it then, but the ship was carrying nearly 3,000 reinforcements for the Japanese garrison on Saipan.

All four torpedoes hit, sinking the ship almost immediately.

Throughout that evening and into the afternoon of June 5, the Blasters stayed within range of the convoy.

Early that night the Shark fired six more torpedoes. That was when it sank both the 7,000-ton Takaoka Maru and its 3,500 troops, and the smaller Tamahime Maru.

The next day, June 6, Chick Clarey nailed three ships in 10 hours with 10 torpedoes. During the counterattack on the Pintado, a depth charge exploded so close it shook the boat from stem to stern.

Lockers flew open, a gyrocompass was knocked out, and a file drawer hurled onto Chief Blair’s head.

“Thus ended seven days and seven nights of continual operations against an enemy with radar equipped planes and escorts,” Blair wrote in a report to Lockwood.

“The pack made a total of 28 end arounds, twenty-three approaches of which two were simultaneous and three were very closely coordinated. Made six attacks, fired thirty torpedoes, made thirty hits.”

It was a performance that is still unmatched in the annals of submarine warfare — even though Blair’s pack mate, the Pilotfish, never fired a single torpedo.

A desultory and anticlimactic three weeks followed. As Blair noted in his journal, “Made a cruise to China and back…sank a Sampan.” And then they went home.

Capt. Leon Blair was later awarded the Navy Cross in recognition of his leadership. And Blair’s Blasters became poster boys for the Brown-Momsen coordinated attack doctrine.

They worked well together as a group. Despite the lack of reliable interboat communications, the three commanding officers and their commodore had managed to stay in close contact during those hectic days. Information on enemy ship dispositions was quickly passed along. Blair was able to coordinate his flotilla’s movements and attacks.

The success of the tactic was no longer in doubt. During the next 14 months more than 100 wolf packs would be unleashed upon Japanese shipping in the Pacific.

Detailed analysis conducted by a Navy research group in early 1945 showed that a three-boat pack could sink or damage up to 40 percent more ships than three submarines operating individually.

As experience grew, lessons learned were incorporated into an always-flexible doctrine. Eventually the pack’s senior captain, rather than the division commander, became the OTC. And wolf pack codes for interboat communications were developed and refined, although radio technology remained the Achilles’ heel of group operations.

By the end of spring 1945, however, the communications issue no longer mattered.

The previous year had been devastating for Japan’s merchant fleet. In 1944 American submarines sank some 2,430,000 tons: more than in the three prior years combined.

The fleet now was all but destroyed, partly due to Babe Brown and Swede Momsen’s carefully crafted wolf pack doctrine, and the aggressive manner in which it was executed by the Navy’s young submarine commanding officers.

RELATED

This article originally appeared in the September 2009 issue of World War II, a sister magazine of Navy Times. To subscribe, click here.