ANNAPOLIS, Md. — As a decorated Navy SEAL operator and explosives breacher, Ryan Larkin was regularly exposed to high-impact blast waves throughout his 10 years of service.

Struggling with the psychological effects of serving in four combat tours and an undiagnosed brain injury, Larkin died by suicide on a Sunday morning in 2017 dressed in a SEAL Team shirt with the medals he earned in service next to him.

“Ryan died from combat injuries, just not right away,” Frank Larkin, Ryan’s father, said.

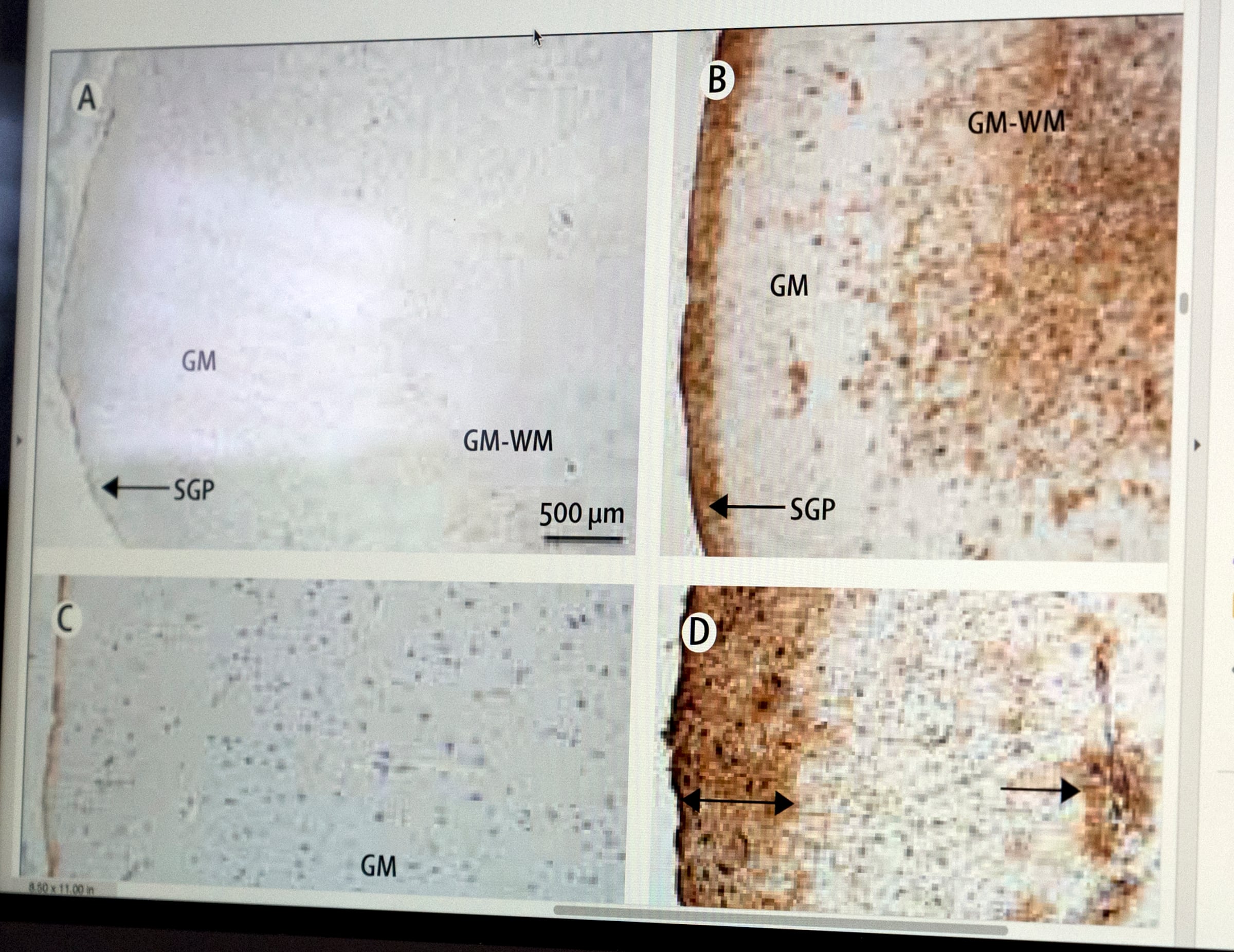

Ryan Larkin’s repeated exposure to blast waves severely damaged his brain by causing microscopic tears in the tissue, internal lining and blood vessels.

Ryan Larkin told his father in the months before his death that he wanted his body to be donated to traumatic brain injury research. The 29-year-old’s brain was examined at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center where a doctor discovered that Ryan had a severe level of microscopic brain injury that was uniquely related to blast exposure.

Sixty-four U.S. service members have been diagnosed with traumatic brain injury as a result of an Iranian ballistic missiles attack on American troops at Iraqi air bases in January.

President Donald Trump dismissed the concussion injuries as “headaches” and “not very serious” injuries relative to other injuries he’s seen. His comments were criticized by veteran advocates, including Frank Larkin, a former Navy SEAL and retired Senate sergeant of arms.

RELATED

Frank Larkin, who stood beside Trump when he signed an executive order to prevent veteran suicides, wrote a letter to the president about the “invisible wounds” Ryan sustained from the concussive effects of high-powered weapons during his time as a sniper and explosives breacher.

Larkin asked Trump to heighten the sense of urgency around the need for scientific research in traumatic brain injuries.

“There’s a lot of people that do not understand what this means and the impact it’s having on our society,” Larkin said.

Each year in the United States an estimated 1.5 million people sustain a traumatic brain injury, according to the CDC. These injuries can range from mild concussions to severe disabilities that result in death.

A CHANGE IN HIS BRAIN

Ryan Larkin enlisted in the Navy and volunteered for the SEAL program shortly after he graduated from Severna Park High School in 2005.

He was known as a loyal friend, an intelligent abstract thinker with a dry sense of humor. He loved the water and was a frequent wakeboarder. Larkin’s attributes made him a respected and relied upon special operations combat medic, sniper and explosives breacher. Ryan Larkin received the Bronze Star, Army Commendation and Navy-Marine Corps Achievement medals with valor, among other awards.

As a combat medic, he volunteered to serve in back-to-back tours in Iraq and then Afghanistan for a total of 12 months.

Larkin deployed on four heavy combat tours between 2008 and 2013, where he would blow through thick walls and doors, fire weapons with a powerful blast and be exposed to improvised explosive device, known as IEDs. In a video, Larkin stands by, his fingers in his ears, as a troop blasts a rocket launcher a few feet away.

“He would say to me, ‘Mom, it would just clear out my sinuses and you could feel it.’ It was so unbelievable,” Jill Larkin said.

The vibrations left microscope tears in Larkin’s brain so small that MRIs and PET scans can’t detect the damage on a living person. Survivors of explosive attacks often report problems of headaches, difficulty sleeping, trouble concentrating, irritability and memory problems. A 2017 study of eight deceased military personnel found that blast exposure produces lesions in the human brain called astroglial scarring.

When Larkin returned home after his third tour, his brain had changed.

“He was a different kid. Totally,” Jill Larkin said.

Ryan Larkin started having trouble sleeping. He complained of headaches and became short-fused. He stopped smiling and his relationships started to erode. Larkin deployed on his fourth tour in Afghanistan’s Helmand Province, an area with a high rate of enemy contact.

When he returned home, he was more anxious and confused. He was hard to talk to, his parents said. When he was able to sleep, he would have nightmares. Larkin began teaching other SEALs explosive breaching techniques in San Diego, where he was exposed to blast waves daily.

Larkin was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. The Navy referred Larkin to several programs, some were helpful, others destructive. The common theme was a prescription for medication, his parents said. Boxes of medication would arrive at their house.

“Every time we turned around, somebody was writing a new prescription for some type of drug,” Frank Larkin said.

LOOKING FOR ANSWERS

Over a two-year period of seeking help, Ryan Larkin was prescribed over 40 medications, his father said. The drugs made him feel worse and he was labeled operationally unfit and mentally unstable. Without a customized care plan, Ryan Larkin started losing trust in the institution he loved above all else.

“He’s the only one that said something is wrong with my head,” Frank Larkin said. “(Ryan) would say ‘Something is wrong with my head. I don’t know what it is. But they keep telling me I’m nuts. I’m crazy.’”

Ryan Larkin was honorably discharged from the Navy in 2016. He was referred to a Veterans Affairs hospital for treatment, which felt like being abandoned, his parents said. The lack of science surrounding traumatic brain injuries led the Larkins to countless doctors and therapists, but they never got a definitive diagnosis.

“You become very vulnerable with a lack of good science to help support your decisions,” Frank Larkin said. The Larkins almost spent themselves into bankruptcy on different treatments.

“When you see someone like Ryan circling the drain, you will do anything,” Frank Larkin said.

Ryan Larkin would have likely retired after a lifetime of Navy service if he was not discharged, his parents said.

“He knew that he wasn’t going to get better and that there was no turning back,” Frank Larkin said. “The system he trusted failed him and turned on him.”

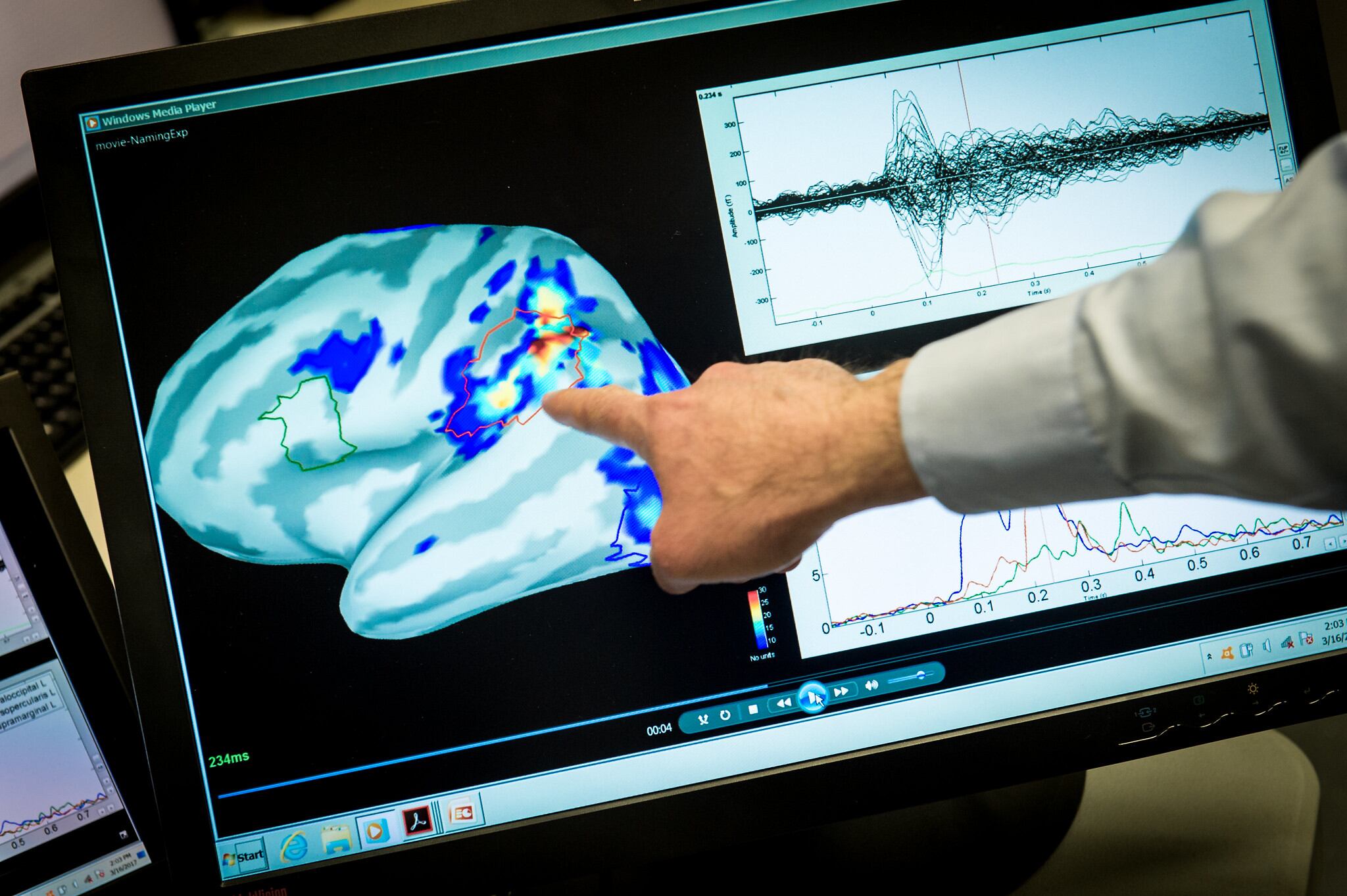

It’s now Frank Larkin’s mission to advocate for more research in traumatic brain injuries and educate the public in hope that one day the disease can be diagnosed before death.

The SEAL community and the Special Operations Command now collects exposure data, promotes a brain donation program to advance the research and has changed tactics to reduce exposures.

In his letter, Frank Larkin called on the president to make TBI and the veterans suffering from it a priority and to address a medical enterprise that he says is unresponsive and too bureaucratic.

RELATED

With advanced research and a holistic approach to care, Larkin hopes more appropriate therapies will give patients suffering from invisible wounds the opportunity to identify the biological connection to mental health issues and the chance to improve their brain health.

“At least we had some answer, not saying that was any better, but it at least gave us an answer why our son became the way he was,” Jill Larkin said.