Although I am teaching a course at Indiana University this semester on the opioid epidemic, I can’t get meth out of my mind.

A colleague of mine was recently carjacked. He was forced to drive at extreme speed throughout the city and escaped with his life only by intentionally crashing his car.

My colleague told me he believes his gun-wielding assailant was suffering an acute psychosis related to methamphetamine use.

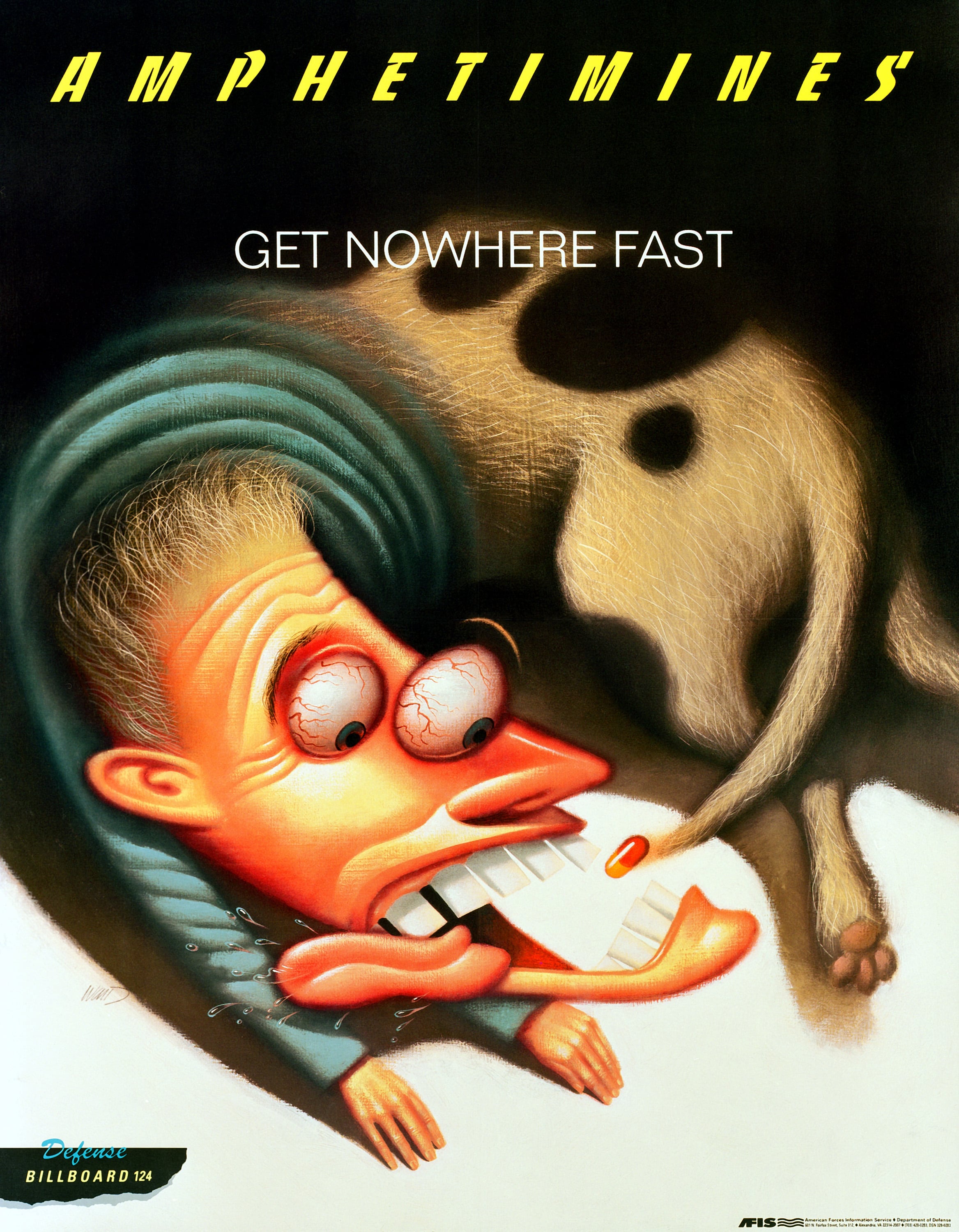

Opioids may get most of the media attention these days, but meth has hardly gone away. Law enforcement seizures of meth are surging in the U.S., up 142 percent between 2017 and 2018. Overdose deaths in 2017 were seven times higher than in 2007.

Just what is meth? Why is it such a grave threat to health? And why does its terrible specter seem to loom larger and larger?

The health effects of meth

Methamphetamine, a powerful stimulant of the central nervous system, has some legitimate medical uses, such as the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. But it is widely trafficked and purchased for recreational consumption, often as crystal meth (think of the award-winning television drama “Breaking Bad”).

Recreational meth users smoke, snort, ingest or inject the drug. Smoking and injection seem to give the greatest rush, but the effect doesn’t last as long. Users often report euphoria, increased alertness and reduced appetite; chronic users may experience paranoia, delusions and unpredictable mood swings. Addicts may exhibit a “binge and crash” pattern, and many try to maintain the rush with continuous consumption.

Chances of addiction are high, and symptoms from withdrawal can linger for months. Treatment is complicated, particularly because many meth users are often also using cocaine, heroin or alcohol.

Meth is directly toxic to the brain; developmental delays are common in meth babies. In adults, it’s associated with an increased risk for Parkinson’s disease. Addicts age at an accelerated pace, and commonly acquire “meth mouth” – tooth loss, tooth decay and tooth blackening.

Those who overdose may develop psychosis or abnormal heart rhythms. Unlike opioid overdoses, which can quickly be resolved if the drug naloxone is available, meth overdoses have no “reversal” agent.

Instead, the meth is suctioned from the stomach. Anti-psychotics can help with psychosis, and anti-hypertensive drugs can reduce acutely elevated blood pressure.

Meth’s dark history

During World War II, meth played a sinister role in the Nazi war machine.

The military, along with German civilians, used a commercial form of the drug – made in Berlin and marketed under the trade name Pervitin – to stay awake, alert and energized.

With Pervitin, factory workers and homemakers alike found they could work longer and harder. Troops called it “tank chocolate” or “pilot’s salt.” Pervitin fueled the Nazis during their “blitzkrieg” invasion of France in 1940.

Wrote one German commander about Pervitin: “Everyone fresh and cheerful, excellent discipline.” Later his assessment became less rosy: “After taking four tablets, double vision and seeing colors.”

The toll meth took on the Germans was immense. It provoked war crimes, stoked psychosis and triggered suicide. As the war progressed, Adolf Hitler received ever-increasing doses of the drug.

No one should be surprised. After all, the German name Pervitin is related to the word pervert (“ill-turned”). It means corrupted or distorted. Meth, as the Nazis discovered, distorts our nature and turns us away from what we are meant to be.

Now, 75 years after the war, and still without an effective drug therapy, a meaningful response to methamphetamines requires three things.

We in the U.S. must recognize the true scope of the problem.

We must make sure meth users have access to counseling and behavioral therapy.

Most of all, our society needs to help individuals and families discover healthier ways to find meaning in life.

RELATED

Dr. Richard Gunderman is Chancellor’s Professor of Radiology, Pediatrics, Medical Education, Philosophy, Liberal Arts, Philanthropy, and Medical Humanities and Health Studies at Indiana University. He is also John A Campbell Professor of Radiology and in 2019-20 also serves as Bicentennial Professor. Gunderman is the author of more than 700 articles and has published 12 books, including “We Make a Life by What We Give” (Indiana University, 2008), “X-ray Vision” (Oxford University, 2013), “Essential Radiology” (3rd edition, Thieme, 2014), and “We Come to Life with Those We Serve” (Indiana University, 2017). Published in 2019 are “Pediatric Imaging” and “Tesla.”