The first landmine I defused was in Cambodia.

Outside of Siem Reap, kids playing in a field found a dulled metal disk the size of tea cup. It was a live Chinese-made Type 72 anti-personnel mine packed with 5.4 kilograms of high explosives, equal measures of TNT and the deadlier RDX.

I strapped on a flak jacket and helmet, and used a metal rod to gently pry the mine from the ground to disarm the device.

It was only one of 10 million landmines still stuck in the ground from the Cambodian genocide. Removing it meant one less casualty.

Over the past decades, international agreements and initiatives helped to reduce the devastating consequences of unexploded munitions, but public outcry played a role, too.

In 1997 Princess Diana made headlines by walking into a mine zone in Angola. Banning landmines was a signature issue for her. In that same year the International Campaign to Ban Landmines was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for its work preventing the use and manufacturing of landmines.

But a policy shift inside the Pentagon has put Princess Diana’s legacy, and the hard work of humanitarian de-mining organizations, at risk.

In a little-noticed Jan. 31 evening press release, the U.S. Department of Defense announced it will cancel former President Barack Obama’s Presidential Policy Directive 37, which largely banned American use of landmines and specific explosive munitions in warfare outside of the Korean peninsula.

As both a U.S. Navy SEAL and a war correspondent, I have served in and reported from some of the world’s most heavily landmined areas — Afghanistan, Burma, Cambodia, Egypt, Somalia and Laos, among others.

Based on what I have seen of the danger and devastation caused by landmines, I believe cancelling PPD-37 sets the wrong precedent for U.S. foreign policy.

Landmines — and similar types of unexploded ordnance — aren’t like other weapons of war.

Their remnants —hidden landmines, cluster munitions, dormant bombs — litter the land long after the cessation of hostilities, and they cause chaos well after formal wars come to a close.

Landmines kill even after the killing ends.

Landmines have been a tool of war for hundreds of years. An ancient 14th century Chinese manual, the Huolongjing, references the use of containers loaded with gunpowder to make a pressure mine.

Gunpowder and weaponry evolved in the centuries since the Song Dynasty disappeared.

Modern landmines are vastly more lethal, and can be deployed by air, blanketing hundreds of acres. The U.S. M16 APM launches four feet into the air and sprays high velocity iron in every direction.

It has a casualty radius of 27 meters.

Once placed in the ground, landmines are not easily removed. Today, more than 110 million landmines worldwide still sleep below the surface. Once buried, landmines locations aren’t tracked, which is why innocent civilians are maimed or killed by weapons by bygone conflicts.

The numbers are staggering: In 2018 alone, landmines killed or maimed almost 8,000 civilians.

More than half of the victims were children.

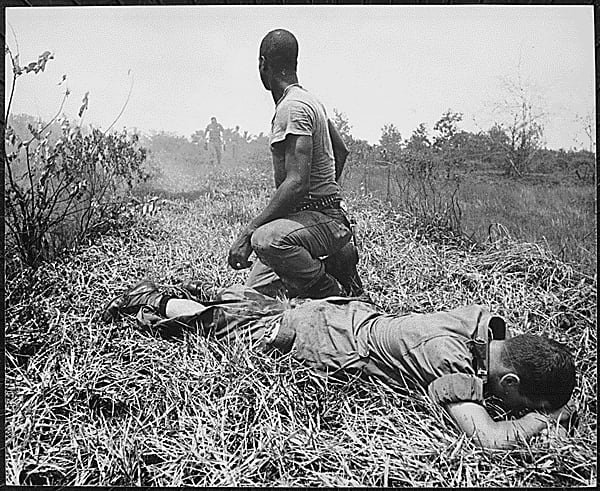

I have seen this firsthand at a home for children victims of landmines in Cambodia.

I met Boreak, a 9-year-old who lost most of his left arm when he picked up a mine that he mistook for a toy. Boreak and I played soccer most of the day, but he really wanted to play guitar.

I watched with sadness as he cradled the guitar in the nub that was left of one arm while he strummed the strings with his good arm.

Boreak was my first friend who was a landmine victim but not my last. In 2009 my friend and fellow SEAL Dan Cnossen stepped on a landmine in Afghanistan.

He lost both legs below the knees.

The wars in some of these regions ended nearly a half-century ago, but the landmines continue to kill every day.

In the first 10 months of 2019, Cambodia reported 71 landmine casualties, half of whom were children. In the markets of the capital Phnom Penh, vendors retail prosthetic limbs the way other countries sell tamales.

In Yemen, I watched as locals were shredded from unexploded cluster munitions.

In Afghanistan, I saw children skip over land that contained mines and undetonated bombs.

In Laos, one of the heaviest bombed countries on earth, practically every village has a a relative who has been hurt or killed by an old explosive.

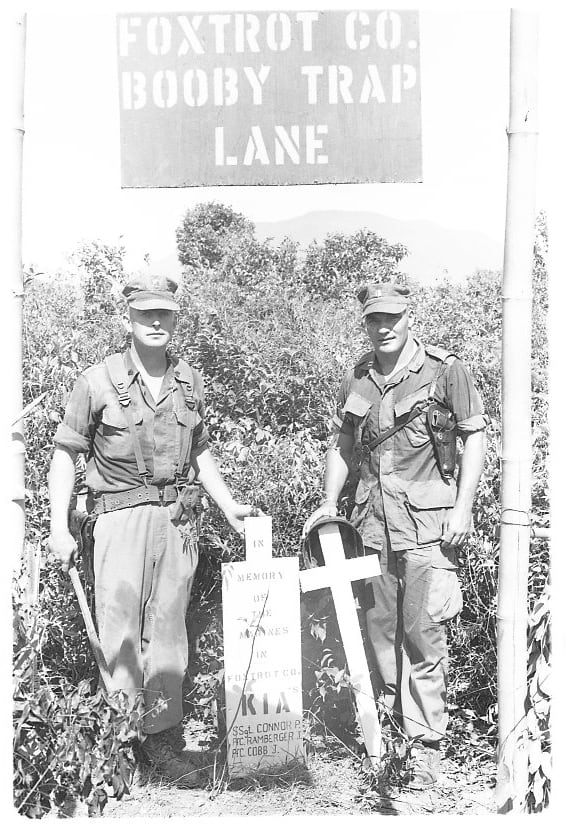

The devastation of unexploded remnants of war has inspired former combatant help reduce the devastating impact of mines.

Out of uniform, I’ve conducted de-mining operations with fellow veterans, working with organizations like The HALO Trust.

This group recruits volunteers — both within communities and from around the world — to help clear unexploded bombs and mines from conflict zones. Their mission is to remove all landmines in the world by 2025.

In the recent past, this goal looked attainable. For some time, it seemed like these awful weapons were the exclusive domain of bad actors like the junta in Burma or the regimes in Syria, North Korea and Iran.

The U.S. provided moral leadership and authority by largely prohibiting the use of these explosive weapons by its military.

Now that’s shifted. Instructed to develop a new policy based on using landmines as a “force multiplier,” the Pentagon is making the wrong move.

Mines aren’t precise and they fail to multiply force in any way that makes sense to those who wage modern warfare.

Contrary to what supporters will claim about so-called “smart mines,” there’s simply no such thing. In fact, these weapons are, universally dumb. They don’t distinguish between soldier and civilian.

And there’s a strategic downside. Landmines create acres of “dead zones.” Because the land they are buried in stays unusable, people move away.

Conflicts that we thought were over continue for years. The mass migrations of human beings trigger new conflicts elsewhere, simply because they can’t go home.

America has no interest in creating endless strife. It isn’t good for our military, and it isn’t good for our country, to let landmines cause conflicts to fester and worsen.

Whatever minor tactical advantage we imagine we gain from using mines is far outweighed by the moral cost of dead children, dispossessed homes and vast swaths of unusable earth salted with unexploded munitions.

In our own time we have seen in the consequences of conflicts that do not end and scars that do not heal.

Promoting the use of landmines and similar munitions creates grave risk and a cycle of endless war that hurts soldier and civilian alike.

The Pentagon ought to seriously rethink its cancellation of PPD-37.

It is a step backward, and likely to detonate on us.

Kaj Larsen served as a U.S. Navy SEAL officer before becoming an award-winning journalist. He has covered conflict zones around the world. In 2016 he traveled to Laos and Myanmar for the documentary Collateral Damage on HBO’s Emmy Award-winning television show VICE. His views do not necessarily represent those of Navy Times or its staffers.

RELATED