Feb. 19, 1945, dawned bleak but manageable.

That morning nearly 800 American vessels, ranging from battleships, cruisers, and destroyers to transports and LSTs, lay offshore a small island in the far Pacific.

On board the transports were 70,000 Marines from three divisions, charged with conquering eight square miles defended by 22,000 Japanese soldiers fighting out of caves, bunkers, and tunnels.

Planning for the battle on Iwo Jima had been under way for more than a year. The Marines were on the ground; the Japanese were in the ground, and they were ready for the siege.

Each man was told to fight to the death, but not before taking at least 10 Marines with him. The Japanese survived on half a cup of water daily and a handful of rice, yet they held out for 36 days.

The last five days they had neither food nor water.

On the first day alone, the Marines suffered 2,420 casualties, including more than 500 killed.

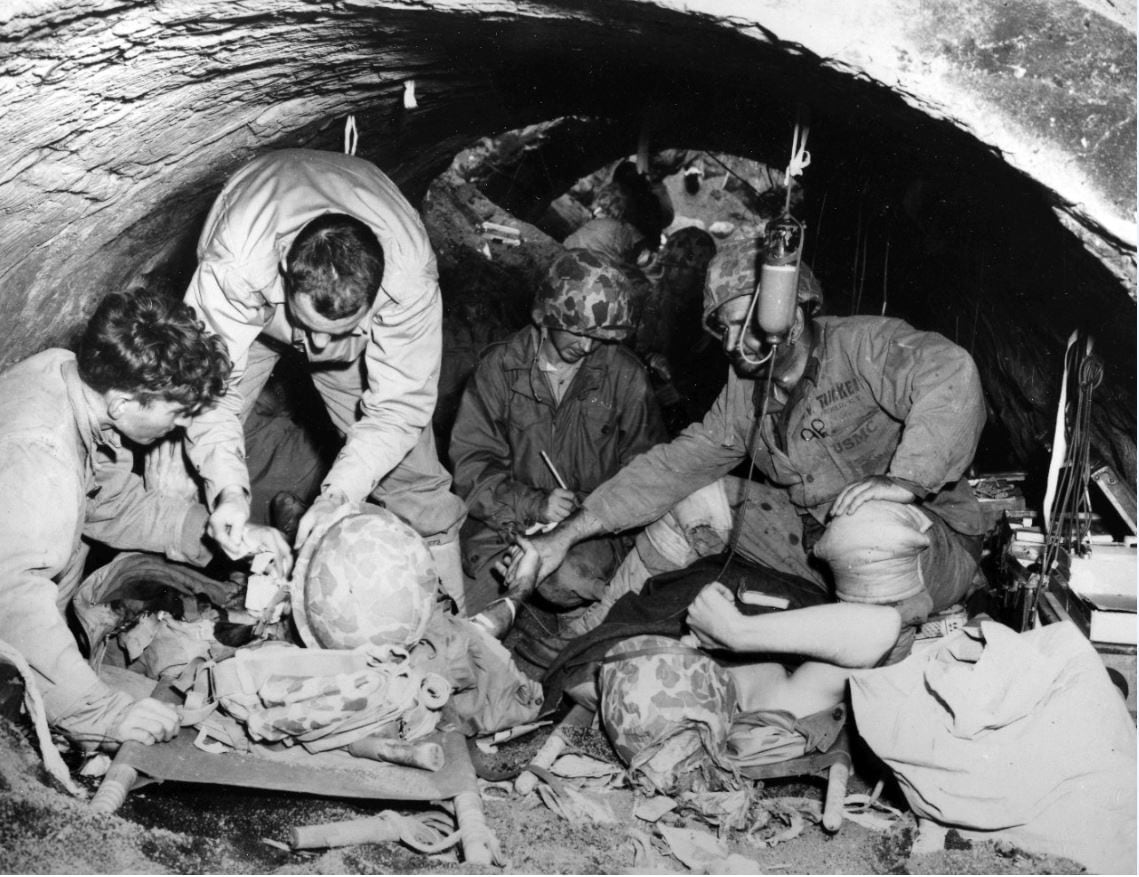

Before the campaign was over, 13 of 24 battalion commanders fell, and 15 doctors were killed, along with 195 navy corpsmen, who were medics on the battlefields.

In those 36 days, 28,000 Marines and soldiers — American and Japanese — were killed, and 16,000 were wounded.

On the following pages, survivors of the battle look back over the decades to recall the Marine Corps’ deadliest campaign.

Pfc. Pete Santoro, rifleman, 24th Marines, 4th Marine Division:

“I joined the Marines in November 1942. What happened was, after I had served three years in the National Guard, I got these papers telling me to report to the Army. I went to the recruiting office in Boston, and I found this Marine major and said, ‘Sir, can I speak to you?’

“I told him I didn’t want to go in the Army because my mother and father came from Italy, and Italy was fighting against us, and I had relatives in Mussolini’s army. I’d said I’d be fighting my own relatives and I’d feel bad shooting at them.

“‘Oh,’ he says, ‘now I understand. Follow me, son.’ He puts his hand on my shoulder, leads me into an office, passes me over to another Marine, and says, ‘I got a ripe one for you.’”

Pfc. Charles Waterhouse, combat engineer, 28th Marines, 5th Marine Division:

“We had a guy named Danaluk from Brooklyn, New York, whose draft number had come up. He wanted to get in the Coast Guard because he lived in Brooklyn and figured he could get a job on a ship patrolling New York Harbor, see? So he said to them, ‘I want the Coast Guard.’ They said, ‘You’re in the Marines.’ ‘No, no, no, I want the Coast Guard.’ They finally convinced him he had no say in the matter and that he was going to be a Marine. So every morning, as he threw the blankets off, his first words, the first thing he’d say was, ‘Oh, that effing draft board!’ Every day. So, in his honor, when the ramp let down on Green Beach, the whole boatload of us hollered, ‘Oh, that effing draft board!’ That was for Danny. The Japs must have thought, ‘Here comes a bunch of nuts.’”

Cpl. James “Salty” Hathaway, Amtrac crew chief, Amphibian Tractor Company, 4th Marine Division:

“Going to Iwo, we were aboard ship before we found out where we were headed, just like Roi-Namur, Saipan, and Tinian. Nobody knew what was coming. The convoy, hundreds of ships, zigzagged continuously, changing direction every 15 minutes. We stopped in the Bay of Guam; some of the convoy dropped off there. From there to Iwo took about 10 days, so altogether we were 30-some days aboard ship, didn’t do a darn thing but sit on our butts.

“The three days of shelling went on as we were approaching. We had these TCS radio sets, and we’d take ’em up topside on the LST and listen to the navy talking to its planes, so we knew pretty well what was going on. We just steamed straight in on D-day. We glimpsed the island out at sea; it was just a shadow.

“When they served steak and eggs, we knew that would be our last meal aboard ship. Every operation we went on they’d give us steak and eggs, and then you had all them dead Marines with steak in them. (Maj.) Gen. Clifton Cates gave us the ‘Godspeed farewell’ message over the ship intercoms. We had heard two Navy pilots had been captured and tied to poles on Iwo and the Japs ran by, cutting them with swords. Gen. Cates said in his farewell speech, ‘You know what went on ashore. Take no goddamn prisoners.’ Those were his exact words. All the time I was on Iwo Jima I saw one prisoner, and a chaplain had him.”

Pfc. Samuel Tso, code talker, Reconnaissance Company, 5th Marine Division:

“We didn’t know we were going to Iwo until we were out there at Saipan. I can’t remember what wave I went in with, but when we landed, there was no fire from the Japanese. But after we went on top and started spreading out, they opened fire. Some of the guys jumped in an artillery crater. We jumped in on the south side of it, and the guys who jumped in on the north side got shot because they were exposed. My personal sergeant was a guy named Barnes; when we started moving forward, he got blown up. He told me to go around to the other side and stay behind. He went straight ahead and stepped on a mine. If I’d followed him, I’d have been killed.

“Let me tell you, I was scared stiff. The only thing that helped me go on was the fact that I was committed to the fellows that I trained with. We were told that you go in as a team; that you must watch out for each other. That’s what kept me going, even though I was scared.

“When we went ashore, our mission was to cut the island in half, but they held some of us behind. They put us by the airfield and said, ‘You hold this for a certain day and then follow.’ My job was to receive and send messages from the ships or the command post or whatever it is. You receive it and send it on. All in Navajo. All the radio guys were Navajos doing code. I don’t know how many there were altogether. I know my recon company had six. All messages went in code. Maj. Howard Connor said he had six Navajo networks going 24 hours, and they sent and received 800 messages without an error.

“On Feb. 23, 1945, just somewhere close to noontime, all of a sudden the radio signaled, ‘Message for Arizona’ [meaning a code talker needed to receive it]. So I just grabbed my papers and my pencil and just sent it. They sent this message: DIBE BINAR NAAZI: ‘Sheep’s eyes is cured; Mount Suribachi is secure.’ Sheep Uncle Ram Ice Bear Ant Cat Horse Itch spelled Suribachi. And it was encoded too. It was sent out, and I caught it there by the airfield. And the Marines that were there saw me writing it down, and they all said, ‘What’s up, Chief?’ All I did was just point up to the flag, and they saw it. Oh gosh, those guys just jumped up and started celebrating there. They forgot the Japanese were still shooting. As I remember, Sgt. Thomas screamed at us, said, ‘Damn you knotheads! Get back in your foxholes there.’ And then the guys stopped celebrating, and they jumped back into their foxholes.”

Capt. Gerald Russell, battalion commander, 27th Marines, 5th Marine Division:

“We were facing away in a kind of crevice, and one of the kids yelled, ‘Look!’ He pointed up, and there on the top of Mount Suribachi we could see this small group of men and Old Glory. It was very emotional. You can’t imagine how I felt. There was an old gunnery sergeant standing near me. He was about six feet two and had been in the Marines for I don’t know how many years — the Old Corps, you know?

“This guy had the most colorfully profane vocabulary I’ve ever heard. How he could conjure up some of these things was just amazing. He never showed any emotion or anything else, and on the fifth day we were coated with that black grime. We barely had enough water to drink, let alone to wash. When the flag went up, I couldn’t say anything. I had a lump in my throat, and I don’t know if I had any tears, but I looked at this guy who I never thought had an ounce of emotion in his body, and he looked at me and you could see tears coming down through this grime on his face, and he said — and I’ll never forget it — he said, ‘God, that’s the most beautiful sight I have ever seen.’

“I’ve said this in Flag Day speeches and stuff—that up to that point we weren’t sure whether we were going to succeed or not. But from that moment on, when the flag went up, we knew we were. It didn’t get any easier, but we knew we were going to win. We were reminded of what we were there for.”

Cpl. Al Abbatiello, combat engineer, 28th Marines, 5th Marine Division:

“I got wounded on the 23rd, the same day the flag went up. Actually I was in battalion aid at that point. We had been working on a cave with a big coastal gun emplacement. One of the guys set a couple of charges up on top because it was surrounded by concrete, and our stuff wouldn’t do anything but make a big loud noise. We figured if we could get something up high, we could drop half the mountain on it.

“The guy with the charge climbed up the side and got it set. We were covering him, and the infantry was covering us. They even brought up a couple of tanks to give us cover. Anyway, he got up there and came back down, but the charge didn’t go off. Something was wrong with the detonator. So I took a charge myself and climbed up and put it on top of the other charge. I waited a decent amount of time and put it on the charge, and I wanted to get away from there in a hurry. Coming down, I tripped. I slipped, fell, and rolled all the way down. There were huge explosions going all over the place. When I hit the hole, somebody said, ‘Oh my God, your face is gone.’ I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ Turned out I was full of blood. Since I fell, I figured all the pain was from the fall, but actually it was a piece of shrapnel, probably from a Japanese grenade that was rolled down there.

“They dug something out of my nose and out of the side of my cheek. Something ripped out the side of my nose and gum, and my cheek was cut wide open. I thought it came from the fall. The lieutenant checking in on us said, ‘Get yourself to the aid station,’ so I went over to the battalion aid midway across the neck. You know what a million dollar wound is, where you get hurt — but not bad, but bad enough so you have to pull out? This young kid corpsman was treating me. He had been on the ship with us. He patched me up, a couple Band-Aids, this and that and the other thing. ‘You didn’t sew it, though,’ I said to him. ‘A million dollar wound, huh?’ He looked at me and said, ‘Get the hell out of here.’

“Near the end of the operation, we had secured the island pretty close, and we were mopping up. I had the squad just going around, blasting anything that would be bad. We went out on patrol, and they put a corpsman to go with six of us. It was that same kid who treated my face injury. Anyway, a charge goes off, and I hear this screaming. There’s a big rock right over the corpsman. He’s lucky, having just enough space under it so it broke his leg but didn’t crush him. We drug him out and sent him to battalion aid, and when we got back that evening, somebody said, ‘Hey, a guy wants to see you over in sick bay.’ So I go to the battalion aid station, and he’s laying on the floor. He’s got a cast on him, and he looks at me and [waves his hand]. I figure he can’t talk loud, so I lean over — and he kisses me. He says, ‘Million dollar wound!’ I say, ‘You son of a bitch!’”

Cpl. Glenn Buzzard, machine gunner, 24th Marines, 4th Marine Division:

“You didn’t see too many Japs. Once in a while they’d run from one cave to another. You more or less seen their fire. You could see dust coming. As soon as we’d see that, we’d zone right in, and when we got up there, they’d be layin’ there.

“The terrain got rougher and rougher because of the catacombs and stuff where the water had washed in amongst it over the years. Some places you could step over a crack and you’d see a big gap deep down in there. Or you’d go around the corner and they’d be standing right there face to face. Whoever shot first was the winner. I saw one Marine shoot another Marine bone-dead right in my squad because he went around this way and the other went around that way and, it was just like I said, you don’t have a split second. You just pull the trigger. Shoot first. Whoever does, they’re the one’s going to win. We had to take the guy that shot the other Marine, take him clear out because he just went berserk.”

Sgt. Cyril O’Brien, combat correspondent, 9th Marines, 3rd Marine Division:

(From one of O’Brien’s March 1945 combat reports, picking up in the midst of an American ambush at a watering hole.)

“Silence fell again except for the occasional rasping scratch of a land crab or the moan of a tortured tree. An animal ran across the trail that was our fire lane, but that was all that came during my watch.

“I had awakened Pvt. Duane Wills to relieve me when two carbine shots cracked in quick succession to our right. We turned in time to see Pfc. Dale Beckett dive into a rock pit as a hissing grenade passed over his head and exploded behind him.

“In a draw below, a Jap slumped over an abandoned enemy satchel, two bullets through his neck. Another Jap hugged the shadowed sides of a draw from where he had thrown his grenade.

“The Jap could not be seen in the shadows, but he made a frantic dash into the moonlight to escape from the draw. The .30-caliber slugs passed through his head. Pfc. Harper R. Rudge guarded the ravine from the opposite wall. Rudge crawled to the edge of the draw, tossed a grenade, then disappeared behind the rock barricade.

“Star shells were falling continually now over the beach area to our front, and in the distance a machine gun clattered.

“‘Doggies [Army soldiers],’ Wills said. ‘The Nips are giving them trouble again.’ He stared back on the trail and hunched his body over the machine gun. I curled up at his feet in an attempt to sleep, but he soon tapped my helmet. Japs were again back on the trail.

“Four walked boldly into our ring, gibbering among themselves. From behind a stone wall a burst of fire cut into the Japs. Two doubled over and fell. Pvt. Patrick J. Cleary Jr. stood upright in his foxhole and cradled his Browning Automatic Rifle.

“Shot through the legs, a Jap dragged his body with his elbows toward a grenade bag but before he had moved three feet another burst from Cleary’s weapon caught him in the chest.

“Another Jap, his right leg shattered, moved with surprising swiftness toward [Pvt. Leo] Chabod’s position. The Marine dropped on the ground beside his companion as a grenade bounced off the parapet and exploded. The Jap was still rushing with a second grenade when a shot from [Pvt. Jack] Woenne’s rifle caught him in the middle. He dropped in a sitting position, dead.

“On the road, the first Jap caught in Cleary’s surprise fire raised his body on his left arm. A grenade sputtered in his hand but this Jap was through fighting. He exploded the missile under his chest.

“Dawn, and the ambushers stirred from cover in the crypts and behind the rocks. Through habit they still spoke in low tones.

“Pfc. Ferdinand Leon found a bloody trail. Someone had dragged a wounded Jap away. He followed the trail for twenty yards but lost it on a jagged slope.

“We filed back past the waterholes, and for the first time I looked in them. Eleven Japs had come carrying canteens, buckets and mess tins. Nine had died here.

“There was not enough water in the well to fill a single canteen.”

Water Tender 3rd Class James Bush, mine layer Terror:

“We brought all our wounded from Iwo Jima to Saipan at the end of February in 1945, resupplied, and went and anchored in a big lagoon at Ulithi, where we went ashore to swim and dive and eat and drink beer. There was nothing there but beach. The beer was Iron City.

“The story of how we got the beer started in Pearl Harbor in January, when we were all fueled up and loading the last of our supplies. Some new young officer pulled up alongside the ship in a weapons carrier and parked it near the end of our gangplank. We told him, ‘Don’t park there,’ because we were unloading trucks and putting supplies on the ship. He said he would park where he wanted to. He was a real starchy-looking guy with a uniform that was too large for him. He didn’t look any older than me, and I was going on nineteen.

“We’d already put all the supplies we could down below. Back on the fantail we had a big old space with some tiedowns. We’d put a hundred tons of potatoes back there. A weapons carrier has lifters on it so it can be picked up and set aboard ship. Well, guess what? I stood up there and watched them guys look around all over the place, no other officers watching them, and they reached over and picked that weapons carrier up and set it onto the ship next to the potatoes, covered it with a big tarp. An hour after that we were backing out of dry dock so we could get out of Pearl Harbor before they put the gate up. They had cables down there to keep enemy submarines out of the harbor.

“When we got to Saipan, they set that weapons carrier off onto the dock, and everybody was riding around. I even went out in it for an hour or two. Some of the guys who pulled that stunt struck a deal with some of the guys on Saipan, military people. They liked that weapons carrier. They were moving to the war zone, and they didn’t have anything like that.

“Our guys said, ‘Well, what have you got to trade?’ They said, ‘We know where there are four pallets of Iron City beer. Dozens of cases.’ Done. So they went on down to the ship, waited till the officer of the deck left his post, and they picked those pallets up, brought them aboard, and moved them to a walk-in cooler. Iron City beer was nasty-tasting stuff, but when we got to Ulithi after Iwo, it was really good, I’ll tell you that. It was worth that weapons carrier.

“I pitied that poor little officer, though, having to walk all the way up through that shipyard, back to his commander saying, ‘Guess what? I lost the weapons carrier.’

"It took us four days to drink up all the beer.”

Pharmacist’s Mate 3rd Class George Wahlen, Fox Company, 2d Battalion, 26th Marines:

“My strongest memory of Iwo was what turned out to be my last day in combat. As we were going up north, a group got hit with heavy fire, and as I was crawling up there, I got hit in the leg. There was casualties right in front of me, so I started to get up, but I couldn’t. I looked down at my foot, and part of my boot had been torn away, and my right leg was all bloody and broken just above the ankle. I pulled my boot off and put a battle dressing on it and gave myself a shot of morphine. Then I crawled up to where the marines were. As I remember, there were about five of them, and they were all pretty well shot up. I think one guy lost a leg, and others were all beat up. I worked with them and bandaged them, and gave them morphine as long as I could. Finally they were evacuated. Then somebody out to our left flank got hit and started hollering for a corpsman, so I crawled out on hands and knees and took care of him too. He could have been 40 or 50 yards out there, so I crawled out and bandaged him up, and we crawled to a shell hole.

“The stretcher-bearers came for us but then dropped me when rifle fire came. I got out my .45 and started crawling toward the enemy. It was the morphine. They finally came and got me and took me to the aid station. Four of us went from there on a truck to the field hospital. My war was over. I think it was March 3. I was scared myself plenty of times. I always remember that feeling of being scared, but the thought of letting somebody down scared me even more.”

Excerpted from IWO JIMA: WORLD WAR II VETERANS REMEMBER THE GREATEST BATTLE OF THE PACIFIC by Larry Smith. Copyright © 2008 by Larry Smith. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. This article originally appeared in the July 2008 World War II Magazine, a sister publication of Navy Times. To subscribe, click here.

RELATED