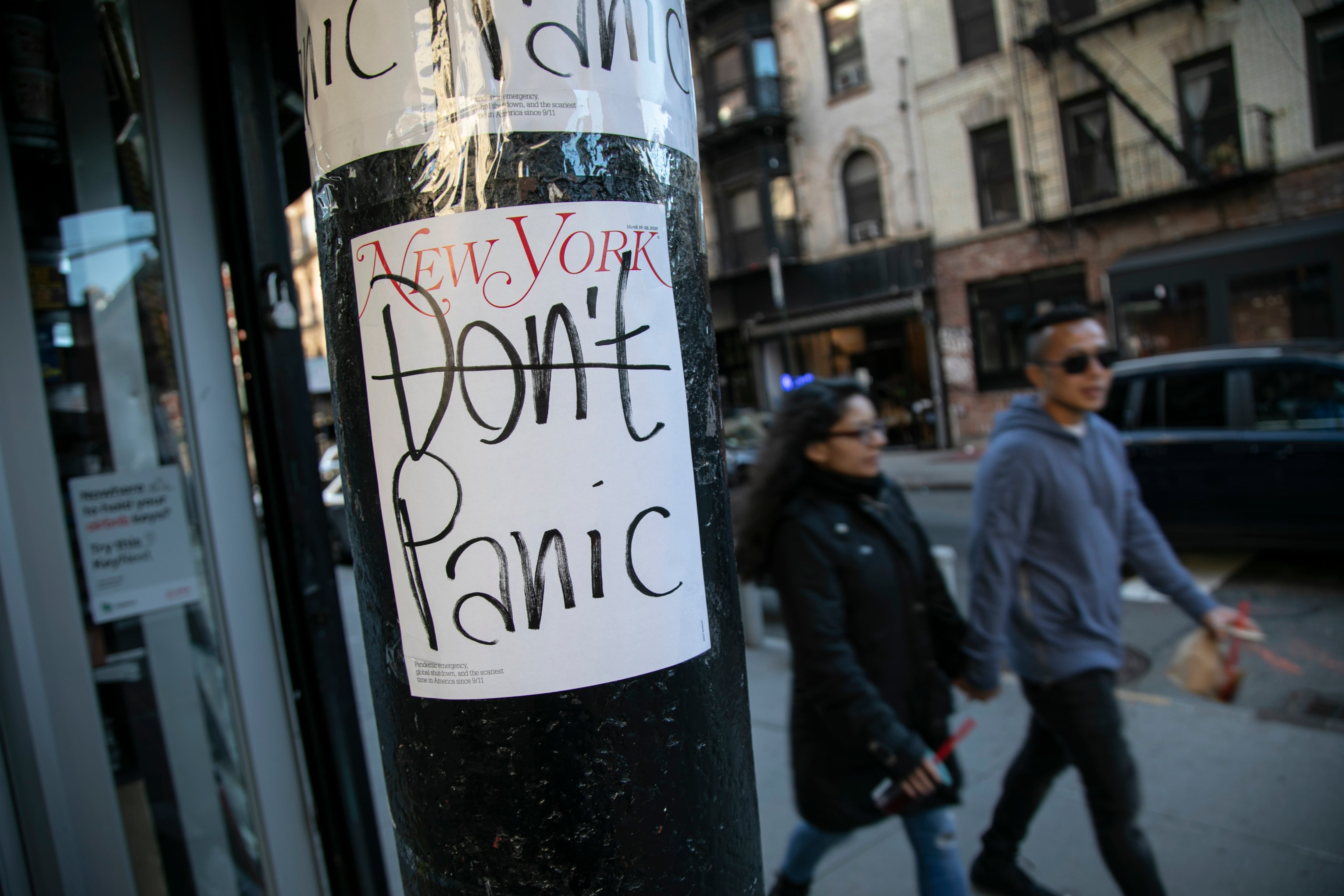

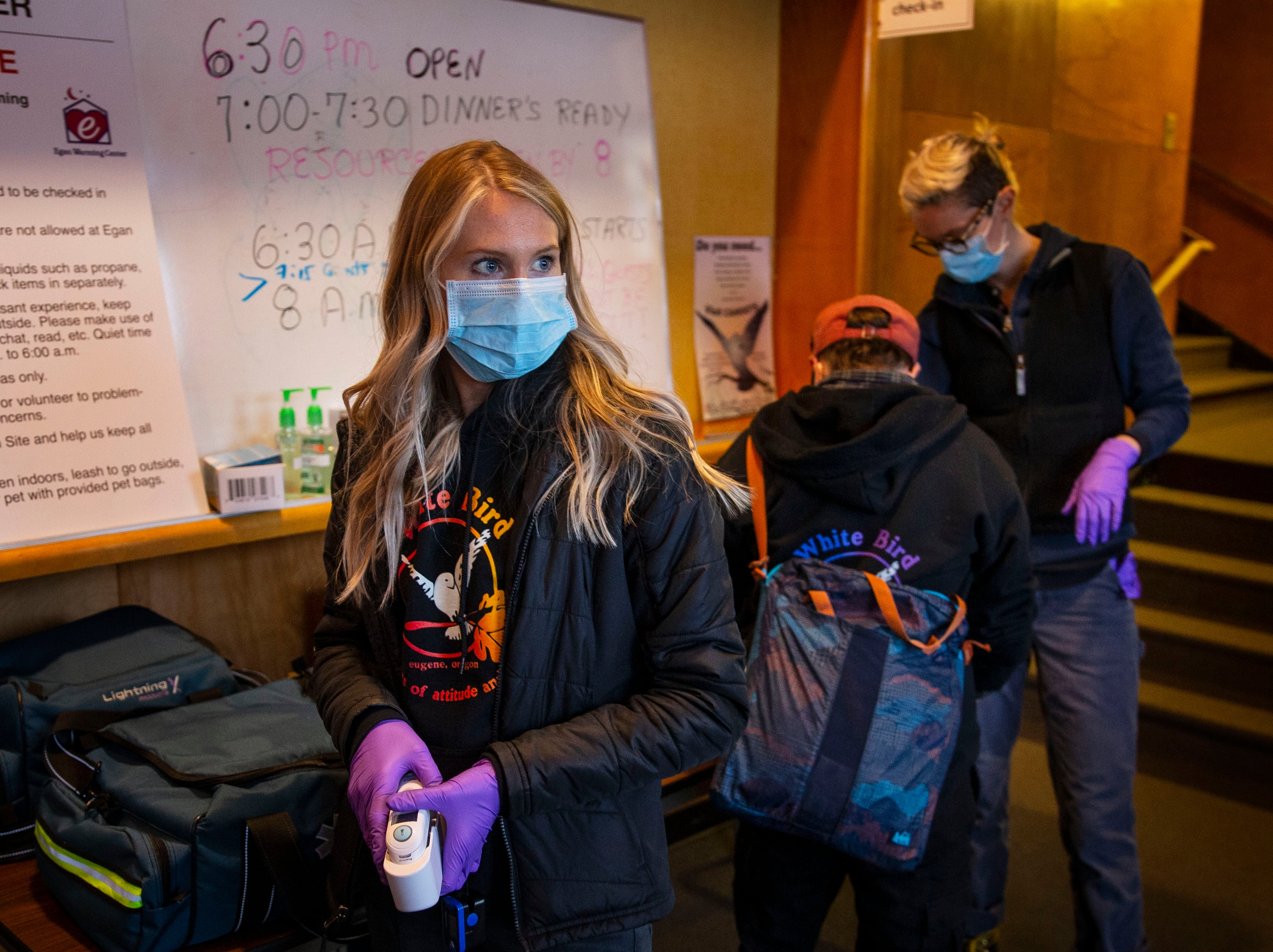

The medical evidence is clear: The coronavirus global health threat is not an elaborate hoax. Bill Gates did not create the coronavirus to sell more vaccines. Essential oils are not effective at protecting you from coronavirus.

But those facts have not stopped contrary claims from spreading both on and offline.

No matter the topic, people often hear conflicting information and must decide which sources to trust. The internet and the fast-paced news environment mean that information travels quickly, leaving little time for fact-checking.

As a researcher interested in science communication and controversies, I study how scientific misinformation spreads and how to correct it.

I’ve been very busy lately. Whether we are talking about the coronavirus, climate change, vaccines or something else, misinformation abounds. Maybe you have shared something on Facebook that turned out to be false, or retweeted something before double-checking the source.

This can happen to anyone.

It’s also common to encounter people who are misinformed but don’t know it yet. It’s one thing to double-check your own information, but what’s the best way to talk to someone else about what they think is true – but which is not true?

Is it worth engaging?

First, consider the context of the situation. Is there enough time to engage them in a conversation? Do they seem interested in and open to discussion? Do you have a personal connection with them where they value your opinion?

Evaluating the situation can help you decide whether you want to start a conversation to correct their misinformation. Sometimes we interact with people who are closed-minded and not willing to listen.

It’s OK not to engage with them.

In interpersonal interactions, correcting misinformation can be helped by the strength of the relationship. For example, it may be easier to correct misinformation held by a family member or partner because they are already aware that you care for them and you are interested in their well-being.

Don’t patronize

One approach is to engage in a back-and-forth discussion about the topic. This is often called a dialogue approach to communication.

That means you care about the person behind the opinion, even when you disagree. It is important not to enter conversations with a patronizing attitude.

For example, when talking to climate change skeptics, the attitude that the speaker holds toward an audience affects the success of the interaction and can lead to conversations ending before they’ve started.

Instead of treating the conversation as a corrective lecture, treat the other person as an equal partner in the discussion. One way to create that common bond is to acknowledge the shared struggles of locating accurate information. Saying that there is a lot of information circulating can help someone feel comfortable changing their opinion and accepting new information, instead of resisting and sticking to their previous beliefs to avoid admitting they were wrong.

Part of creating dialogue is asking questions.

For example, if someone says that they heard coronavirus was all a hoax, you might ask, “That’s not something I’d heard before, what was the source for that?”

By being interested in their opinion and not rejecting it out of hand, you open the door for conversation about the information and can engage them in evaluating it.

Offer to trade information

Another strategy is to introduce the person to new sources.

In my book, I discuss a conversation I had with a climate skeptic who did not believe that scientists had reached a 97 percent consensus on the existence of climate change. They dismissed this well-established number by referring to nonscientific sources and blog posts.

Instead of rejecting their resources, I offered to trade with them. For each of their sources I read, they would read one of mine.

It is likely that the misinformation people have received is not coming from a credible source, so you can propose an alternative. For example, you could offer to send them an article from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for medical and health information, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change for environmental information, or the reputable debunking site Snopes to compare the information.

If someone you are talking to is open to learning more, encourage that continued curiosity.

It is sometimes hard, inconvenient, or awkward to engage someone who is misinformed. But I feel very strongly that opening ourselves up to have these conversations can help to correct misinformation.

To ensure that society can make the best decisions about important topics, share accurate information and combat the spread of misinformation.

Dr. Emma Frances Bloomfield is an assistant professor of Communications Studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. She researches the intersection of science and religious rhetoric, particularly around issues of climate change, human origins and the body. She teaches classes on rhetoric and persuasion and is interested in all aspects of argumentation and pedagogy. Her recent research examines contemporary challenges to science education and strategies for climate communicators.

RELATED

Navy Times editor’s note: The debunking site Snopes isn’t perfect, a point its information desk makes clear. But outlets that make efforts to check their facts often are good tools to use to detect misinformation. We also changed the headline. The author objected to “How to tell Becky her stupid essential oils won’t stop the coronavirus.” While we changed the headline, we won’t change our sentiment about that.