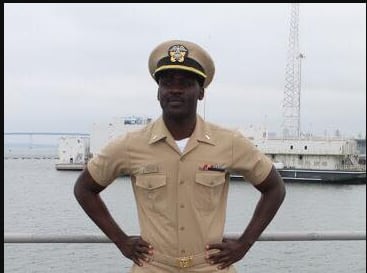

It’s been just more than two years since Lt. j.g. Asante McCalla went missing aboard the guided-missile cruiser Lake Erie.

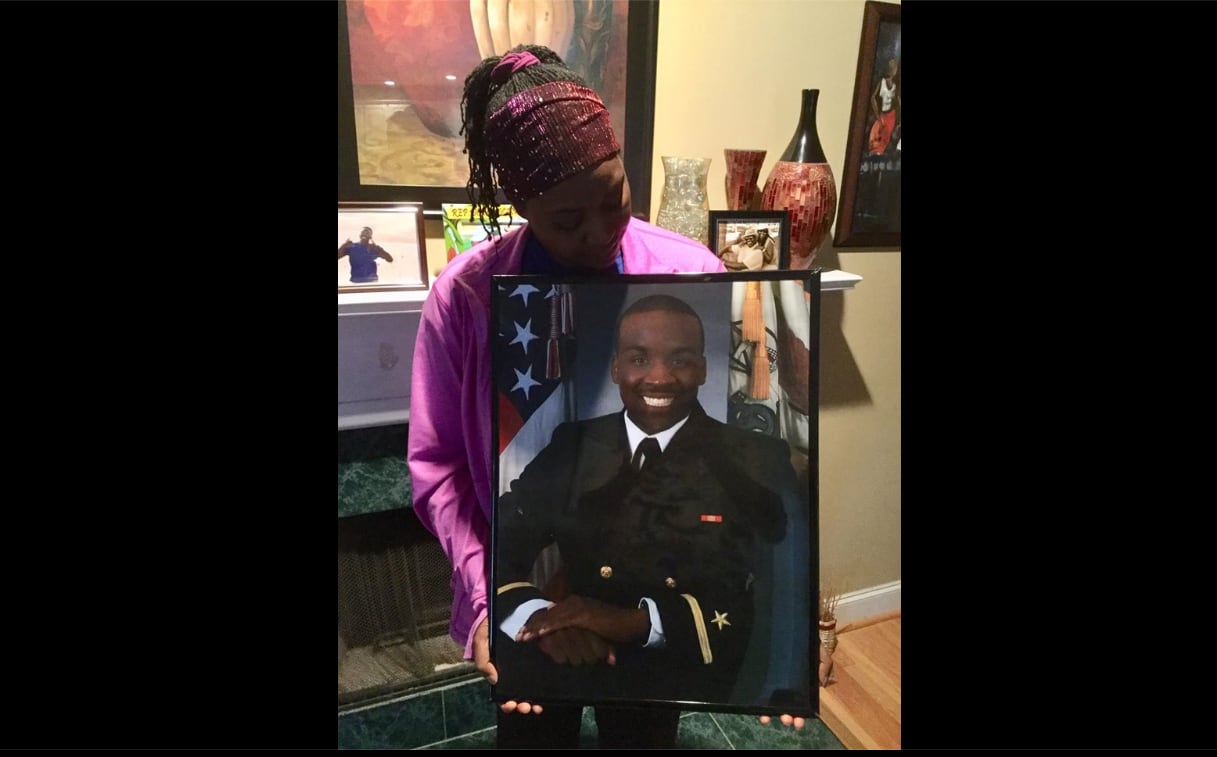

His parents, Alicia and Howard McCalla, have received no answers from the Navy on how their only child died.

The 24-year-old Atlanta native disappeared Aug. 19, 2018, while the warship was participating in an exercise off San Diego.

He didn’t show up for his 6 a.m. watch shift that morning, and man overboard was sounded about 40 minutes later, according to a line of duty investigation into the junior officer’s death obtained by Navy Times.

A massive search of the sea ensued, but was eventually called off when the search proved fruitless.

RELATED

Not knowing whether her son accidentally fell, or killed himself, or if something more nefarious took place, haunts Alicia McCalla.

She and her husband fear that the long time taken in finding out what happened to their son could mean that foul play was involved.

They also wonder how someone could disappear aboard a modern warship.

“That was my only child,” Alicia McCalla, a Marine Corps veteran and educator, told Navy Times. “And I could not return to my life as normal.

“They have not provided this grieving mother with closure, and they should be ashamed and embarrassed of that.”

The Navy’s line of duty investigation finalized this spring reached no conclusion as to how McCalla died.

But it does show that the junior officer struggled to fit in with the ship’s other officers and struggled to obtain his officer of the deck, or OOD, and surface warfare officer, or SWO, qualifications.

His mom worries that his race played a role in his wardroom isolation.

A Naval Criminal Investigative Service investigation into McCalla’s death remains ongoing, and Howard McCalla said they have been told the report is going through a final “quality assurance” review.

NCIS officials declined to comment on the investigation’s status.

“NCIS is conducting a thorough investigation to determine the facts surrounding the death of Lt. j.g. Asante K. McCalla as we do in response to all non-combat, medically unexpected fatalities of Department of the Navy service members,” spokesman Jeff Houston said in an email. “Out of respect for the investigative process, NCIS does not comment on or confirm details relating to ongoing investigations.”

“The Navy takes the loss of a Sailor extremely seriously, and so time was given to ensure all possible investigative leads were exhausted, in hopes of better understanding the circumstances leading to Lt. j.g. McCalla’s loss,” Cmdr. John Fage, a spokesman for the San Diego-based U.S. 3rd Fleet, said in a statement.

Whatever the reason for the delays, not knowing what happened has taken a toll on the McCallas.

Alicia McCalla said she suffered a nervous breakdown and struggled to return to work.

“The apologies and the prayers are nice, but give me some answers,” she said. “What happened to my child? Why can’t you tell me? You should be able to tell me. And shame on you for not being able to tell me.”

“Let us move on in our life,” said Howard McCalla, a school principal. “That’s all we want.”

While the McCallas praised NCIS agents for keeping them informed of the investigation’s progress, they also feel like the lack of answers is just the latest misstep in how the Navy handled their son’s disappearance and death.

McCalla’s parents lamented at the time of his disappearance that they were getting updates to the search and rescue efforts through “newspaper accounts” instead of official channels.

“The Navy Times has been given more information than we have been given about the missing or disappearance of our son,” Alicia McCalla said.

They posted a video to Facebook searching for answers as well.

These days, the grieving mom said she hopes that anyone who served with her son aboard the Lake Erie, and who knows what happened to him, will step forward.

“It’s unnatural for him to go before me,” she said.

‘If it was easy, everybody would have a SWO pin’

While the Navy’s line of duty investigation makes no determination regarding what happened to McCalla, it notes the parallel NCIS effort that “included numerous interviews, forensic analysis, searches, and undertaking possible leads.”

“The record is clear that as a Sailor and Officer in the United States Navy, LTJG Asante McCala served his nation faithfully and well,” the investigator wrote. “His loss is heartbreaking and has been felt by USS LAKE ERIE and her crew.”

McCalla was known as a pleasant and positive officer who cared about his enlisted sailors, according to the investigation.

Before his disappearance, McCalla would FaceTime regularly with his parents.

While offering fatherly pointers on how to deal with the razor bumps that often afflict Black men after shaving, Howard McCalla recalled telling his son that he would need to learn what his enlisted sailors did each day before he could effectively lead them.

“Before you can lead somebody, you’ve got to know what they’re doing,” he recalled telling the lieutenant. “As an officer, you’ve got great responsibility.”

At the same time, however, McCalla was described as “aloof” and reportedly had “difficulty interacting with his peers and senior enlisted,” the investigator wrote.

McCalla stood his standard 6 a.m. to 9 a.m. OOD watch on Aug. 18, but was excused from his evening watch so he could conduct his second mock-SWO board that evening.

He was last seen at 11:30 p.m., hours after that board did not turn out well, according to the investigation.

He had been having difficulties obtaining his OOD and SWO qualifications and had twice been removed as a division officer.

“He was a strong-willed person, which sometimes caused contention between him and … fellow Division Officers,” a Lake Erie member, whose name is redacted in the report, told investigators.

While stressed over quals, McCalla was also excited about his next duty station.

“He was smiling, we were joking with each other,” Howard McCalla recalled of their last FaceTime conversation before his son disappeared. “I said, would you move your big head so I can see the flag?”

In the months leading up to his disappearance, McCalla had excelled as the ship’s main propulsion officer.

“He was doing well and had shown significant progress on his OOD qual,” the member said. “So, overall I was pleased with his performance.”

As a Marine Corps veteran, Alicia McCalla would give her son advice about the politics of the military.

“He had his struggles, I can’t lie about such a thing as that,” she said. “He was definitely much more loved with the enlisted than he was with the other officers. He had to learn how to navigate that.”

While she said she is hesitant to speculate and wants to see the final NCIS report, the mother fears her son had a hard time fitting in because of his race.

“Sometimes, when you’re a professional African American, you have to learn to navigate all-white environments,” Alicia McCalla said. “It’s a struggle and a stress sometimes, to be the only African American with a degree, making a decision.”

“I think the Navy needs to do something about how they treat officers of color,” she added. “How they make them feel welcome. How they help them get to the next level and the support that they offer them.”

McCalla told his dad about his struggles with quals during their FaceTime chats.

“I said, nothing’s going to be given to you,” Howard McCalla said. “I taught you that your whole life. You’ve got to work hard for it. If it was easy, everybody would have a SWO pin. Everybody would be a doctor.”

“You’re right, pop,” he recalled his son saying.

After underperforming on the second mock-SWO board Aug. 18, shipmates reported that McCalla “was feeling down.”

“I asked him how it went, but he told me that he did not want to talk about it at that time,” the shipmate said.

McCalla said he wanted to speak with a chaplain, but since there was no chaplain assigned to the ship, someone suggested he talk to the Lake Erie’s independent duty corpsman, according to the investigation.

The mock board members had “offered to follow-up with LTJG McCalla to develop a way forward to help him qualify SWO,” the investigator wrote.

In her endorsement of the investigation, the Lake Erie’s commanding officer at the time, Capt. Christine O’Connell, acknowledged the challenges McCalla faced.

The junior officer was “experiencing a greater than normal level of stress but was also receiving assistance and encouragement from the Wardroom and seemed to be coping and looking forward to completing this phase of his qualifications,” she wrote.

“As with many professional milestones, Surface Warfare Officer qualification is a justifiably demanding process,” O’Connell noted. “Each person experiences and handles this stress and the demands placed upon them differently.”

Over the past two years, the McCallas have at times wondered how their son could even go missing aboard a modern warship.

The investigation found that the aft lookout sections were “active and alert” and made no object in the water reports, but Howard McCalla believes someone must have seen something.

“What will always trouble me to the rest of my life is that a ship doesn’t sleep,” he said. “Somebody’s always on a watch, and you’re going to tell me nobody sees another servicemember walking around? I’ll never buy that.”

“That’s just my thought as a dad that lost his child.”

‘We told him to look out for his fellow man, and he did’

McCalla grew up in Atlanta, was active in his high school’s ROTC program and attended Morehouse College on a Navy scholarship, where he worked to improve the ROTC’s presence and facilities at the historically Black college.

He arranged to have Black admirals and generals speak at the school, to help foster interest among the student body, his parents said.

The McCallas strove to instill a sense of altruism and selflessness in their boy, taking him to soup kitchens during the holidays and having him pick out old toys to give to charity as Christmas neared.

“We told him to look out for his fellow man, and he did,” Howard McCalla said.

After his death, Alicia McCalla learned that her son had taken those altruistic lessons to heart.

“As a parent, you don’t always get a chance to hear from people how your children impacted them,” she said. “We overwhelmingly received so many cards and calls from people … telling us how Asante changed their lives, how he encouraged them, how he helped them feel better, how he pushed them to go to school or get extra education.”

As they try to move forward in the unthinkable manner known only to parents who outlive a child, the McCallas need to know what happened.

That will begin with the Navy’s final determination as to how Lt. j.g. Asante McCalla died, whenever that comes.

“For whatever reason, it’s just taking them an incredibly long time to come to a conclusion,” Alicia McCalla said. “And it shouldn’t take this long. Two years is just too long.”

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.