For reasons that will remain unknown, something set Macoy Hicks off on Feb. 1, 2019.

In a passageway outside the legal office aboard the aircraft carrier Nimitz, shipmates startled as the junior sailor screamed and banged his head against the wall.

Whatever the cause, the breakdown signaled the grim crescendo to a hard couple of years in uniform for the 20-year-old Albany native.

Hicks’ first duty assignment working sailor funerals in the Navy Ceremonial Guard had haunted him.

A traumatic brain injury, followed by personality changes, insomnia, depression and fruitless visits to Navy mental health providers, left Hicks feeling like nobody in the sea service cared about him.

RELATED

He had tried to drink himself to death six months before that outburst on the Nimitz, and a raft of disciplinary issues had taxed his command’s patience.

Two senior chiefs tried to calm Hicks during the breakdown.

“I’m tired of this fucking shit,” he uttered.

That was enough for Nimitz leadership, and Hicks was promptly charged with insubordination.

Six days later, he pleaded guilty at a summary court-martial and was sentenced to 25 days at the Army-run military jail aboard Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington, about an hour’s drive from the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard where Nimitz was undergoing maintenance.

En route to the jail, his Navy handlers later recalled Hicks saying he belonged in a hospital.

Soldiers working intake at the jail notated Hicks’ past suicide attempt and mental health issues, but the Navy didn’t give the jail any heads up regarding the full extent of the sailor’s troubled history.

A full mental health assessment was delayed for days due to an historic snowstorm and resultant staffing shortages. But several jail staffers still noted Hicks’ precarious mental state in the interim.

And while no staff ordered Hicks to be placed on suicide watch, they allowed him to receive a tan riggers belt and other inmate kit.

On the morning of Feb. 11, Hicks used that belt to end his life in the corner of his bravo block cell.

His parents, Jolee and Michael Hicks, were in town visiting but hadn’t been allowed to contact their only son after he was processed into the jail.

They say they weren’t told of his death until 12 hours later.

Since then, they’ve battled the Navy and Army to get every record they can that might explain what happened to their boy.

As the services continue to grapple with suicide in the ranks, those records raise questions about whether the Navy did enough to help the junior sailor at critical junctures, and whether, in the end, the Army failed to protect Macoy Hicks from himself.

They also show that Aviation Boatswain’s Mate (Handling) Airman Hicks suffered for years in the Navy before his death, far from home and plagued by mental issues he did not appear to fully understand, desperate for help from the institution to which he swore an oath.

“I am broken,” he told a Navy psychologist less than six months before he died. “I have a ghost on my back.”

Hicks was one of at least 73 active-duty sailors to kill themselves in 2019, according to Pentagon data.

“We want people to know that Macoy’s death could have been prevented if just one person in his command, or the person handling his care, showed him some compassion or listened to his cries for help,” the Hickses told Navy Times.

The services’ internal probes into Hicks’ suicide found no fault by those charged with caring for the junior sailor. His parents view the investigations as incomplete, self-preserving whitewashes.

“This should never have happened,” they said.

Army officials told Navy Times that Hicks was the only prisoner suicide to take place in an Army jail in at least five years.

Legal recourse

A law change now provides the Hickses a route to force the services into a legal reckoning over their son’s death.

A provision folded into the 2020 defense policy bill for the first time allows survivors and injured servicemembers to file the equivalent of medical malpractice claims against the services, a sea change for advocates of overturning the Feres Doctrine, a decades-old legal stricture prohibiting troops injured on active duty from suing the government for malpractice under the Federal Tort Claims Act.

The Hicks’ attorneys filed their claim in December, joining at least 277 others seeking $3.25 billion in damages from the four services as of this spring.

Their claim seeks between $4.9 and $6.4 million, but his parents say the filing is about more than money; it’s about ensuring other servicemembers don’t fall through the system’s cracks as well.

“They just are waiting for the families to give up and remain silent,” Michael Hicks said. “That will never happen.”

The Hicks’ claim may prove to be one of the first big tests of this nascent system, even as questions remain about how such claims will be decided.

Pentagon officials have referred questions about the process to guidance posted online, which critics say does not adequately explain how the process will work.

Such specifics remain “enshrouded in darkness,” according to Dwight Stirling, an attorney and National Guardsman who founded the nonprofit Center for Law and Military Policy and has advocated for overturning the Feres Doctrine.

Stirling noted that the services were mandated by Congress to create such a process but have been left to craft that process themselves.

“Who will be on the panels?” he asked. “What are their qualifications and biases? The rules allow claims to be evaluated by nameless officials in secretive offices.”

Stirling also noted that rights afforded a plaintiff in a civilian lawsuit are not part of the military claims process, and he questioned the potential for conflicts of interest.

“No agency is good at policing itself,” he said.

For the Hickses and their civilian attorneys, Michael Berens and Darrin Bailey, reaching a point where they had the evidence to file a claim was a challenge on its own.

The family had to submit Freedom of Information Act records requests for the investigations into what happened to their son.

But nearly all the names of those interviewed as part of those investigations were blacked out, the malpractice claim notes, “making it exceedingly difficult to investigate and understand the full nature of what transpired.”

Army officials said those redactions were made in accordance with federal privacy laws.

Berens told Navy Times he has been waiting more than a year for the Army to produce surveillance footage from the cell block where Hicks died.

The Navy has yet to provide full records regarding the pre-confinement exam a Nimitz senior medical officer performed on Hicks before he was sent to jail, he added.

While the Army’s 15-6 investigation doesn’t lay blame upon any jail personnel, it does suggest the junior sailor failed to take advantage of resources before his death.

“Prisoner Hicks had every opportunity to seek help during his confinement,” wrote the investigating officer, whose name is redacted in the copy provided to Hicks’ family.

The Naval Criminal Investigative Service’s investigation largely repeats the Army’s no-fault findings, but also cites Nimitz shipmates who reported Hicks previously saying he wanted to kill himself.

Navy and Army officials declined comment for this story, citing the ongoing claims.

RELATED

But early last year, before the COVID-19 pandemic and before the Hicks’ claim had been filed, Army officials told Navy Times that several policies had been changed at the Lewis-McChord jail following Hicks’ death.

Those include special handling of incoming prisoners with behavioral health issues or prior suicidal ideation, not issuing belts and shoelaces to those who haven’t undergone a full mental health assessment and more staff training.

While the Army 15-6 states that Hicks failed to take advantage of jail resources to help himself, the Army said in a statement last year that Hicks demonstrated “several protective factors” during in-processing, “including help-seeking behavior, denial of current suicidal ideation, and active planning for a future road trip.”

“Therefore, medical and behavioral health professionals judged Hicks was not at imminent risk for self-harm,” according to the statement. “As a result, he was not placed under suicide protocol and was provided the standard clothing issue that prisoners receive upon in-processing.”

But staffers noted Hicks’s distress for days preceding his suicide, according to the Army 15-6.

And a few hours after his death, a behavioral health specialist reviewed Hicks’ file and concluded that she would have included him in the jail’s “high interest list” of prisoners to be closely monitored, the investigation states.

‘The screams he heard’

Hicks grew up around Albany, New York, and entered the Navy as a high-energy teenager who loved basketball, Magic the Gathering and video games.

The 6-foot-2-inch teen would sometimes walk around in a banana costume for laughs, his family recalled.

His first duty assignment after basic training with the Washington, D.C.-based Ceremonial Guard began in April 2017.

There, according to his family, Hicks struggled with the job’s grim mission, particularly the services and homecomings of sailors lost in fatal ship collisions that summer.

“Macoy reported to his family that the screams he heard during the burials of Sailors who died in the USS Fitzgerald at-sea mishap haunted him,” the claim states. “Macoy was convinced that his ongoing and increasing feelings of mental despair were the result of trauma triggered by supporting burial after burial.”

Hicks’s issues worsened in September 2017, when he hit his head and was knocked out in a bicycle accident, sustaining a head injury in the process, according to the claim.

He was diagnosed with head trauma and a concussion and was treated at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, according to the claim, which cites Hicks’ medical records throughout.

While Hicks’s medical care at Walter Reed was described as sound, the junior sailor increasingly struggled with his Ceremonial Guard duties.

“He was acutely aware that his superiors and fellow sailors noticed his frequent appointments, and he personally became worried that his own skills were atrophying,” the claim states.

The junior sailor became chronically late for duty and his personal appearance failed standards, even as he reported being unable to sleep and struggled with the noise of rifle salutes, according to the claim.

In late 2017, Hicks told providers he was only getting two hours of sleep a night when not taking medication.

By January 2018, headaches and forgetfulness plagued him, even when he made to-do lists on his phone.

Hicks left the Ceremonial Guard the following month, and after a brief training detour in Pensacola, Florida, he reported for duty aboard the Nimitz in April 2018.

RELATED

‘Not adjusted well’

Much of the medical negligence claim filed by the Hicks family attorneys focuses on allegedly subpar care he received from the Nimitz’s ship psychologist, Lt. Alicia Murray, who was tasked with seeing after the mental health of Hicks and thousands of other sailors.

The claim alleges that Murray “failed to familiarize herself” with Hicks’ traumatic brain injury or to recognize that his issues were tied to that injury.

Navy officials declined to make Murray available for comment for this report, and she could not be independently reached for comment.

While the NCIS investigation suggests Hicks was far from a model sailor on the Nimitz, the family’s claim argues that such issues stemmed from his head injury, subsequent mental health struggles and lack of care.

The junior sailor’s problems were evident to some of his Nimitz shipmates, according to the NCIS investigation.

“(Hicks) advised he had thoughts of jumping off the flight deck or drinking himself to death,” one sailor told investigators.

In a chain of command recommendation sheet included in the NCIS investigation, his superiors questioned the junior sailor’s place in the sea service. He had been with the ship for about six weeks as of the mid-June 2018 report.

Hicks “has not adjusted well since transferring from previous command,” his unit’s lead chief wrote. “He is constantly late for morning muster and has emotional breakdowns. He has seen the Chaplain (twice) and is scheduled for ‘Resiliency Counseling.’”

At a nonjudicial punishment hearing that month, Hicks admitted he had “a lot of issues to fix.”

During an August 2018 visit with the ship psychologist, Hicks “reported that he has a nightmare of ‘a little girl crying at a funeral’ and that he continually thinks about the funerals he was in,” according to charting notes cited in the family’s claim.

The next month, Hicks tried to drink himself to death, according to records.

He was soon transferred to Madigan Army Medical Center for in-patient treatment and enrollment in the Sailor Assistance and Intercept for Life, or SAIL, program, which provides care and treatment for fleet members experiencing suicidal thoughts.

Notes from an Oct. 3 visit with Murray show Hicks reporting that he hadn’t eaten for three days, had slept less than two hours in that time “and is starting to see things.”

Hicks’ command referred him to in-patient alcohol treatment at Madigan on Oct. 30, and he spent the next 27 days there.

Tests conducted that day showed him suffering from “significant depression,” high anxiety and post-traumatic stress, according to the family’s claim.

‘Not salvageable!’

Roughly a month before Hicks killed himself, records suggest his chain of command was through with the young man.

He received non-judicial punishment again on several charges, including unexcused absence and drug use, according to the NCIS investigation.

He had been counseled at least 10 times for unexcused absences since his June 2018 NJP.

“(Hicks) is a recurring discipline problem,” his chief wrote on a chain of command recommendation sheet dated Jan. 9, 2019. “He has been to every form of counseling/treatment the command offers. Not salvageable!”

Hicks was busted down to E-1 and received further restriction and pay docking, according to records.

In a letter that Hicks wrote to the ship’s commanding officer on the day of his NJP, included in the family’s claim, he admitted that he “struggled both as a person and as a sailor.”

“I was battling some serious sleep issues alone,” he wrote. “From drinking almost every day to sleeping twice a week and what little sleep I did get was riddled with nightmares.”

“This cycle continued to the point where I saw no reason to live in September of 2018.”

‘Visibly not okay’

Colleen Dibble got to know Hicks while serving aboard the Nimitz, and she witnessed the February 2019 breakdown that led to his insubordination charge, court-martial, confinement and death.

In a statement included in the claim, Dibble recalled telling the ship’s psychologist and Navy attorneys that Hicks needed to be evaluated given his “PTSD and frustrations.”

“I may have repeated this 10 or so times within that week, mostly falling on deaf ears,” wrote Dibble, who later left the service. “He was visibly not okay.”

Nimitz’s leadership “was so concerned” about the carrier’s ongoing 15-month maintenance at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard that “they did not even have a memorial service for Macoy,” Dibble alleged in her statement.

“The command did not take him seriously,” she wrote.

Nimitz officials referred questions about whether a memorial service was held for Hicks to Rear Adm. Kevin Lenox, who commanded Nimitz at the time of the sailor’s suicide.

Now assigned to U.S. Central Command, Lenox did not respond to repeated requests for comment submitted via CENTCOM spokesman Capt. Bill Urban.

‘A triggering event’

Hicks was processed into the jail in the early evening of Feb. 7, 2019.

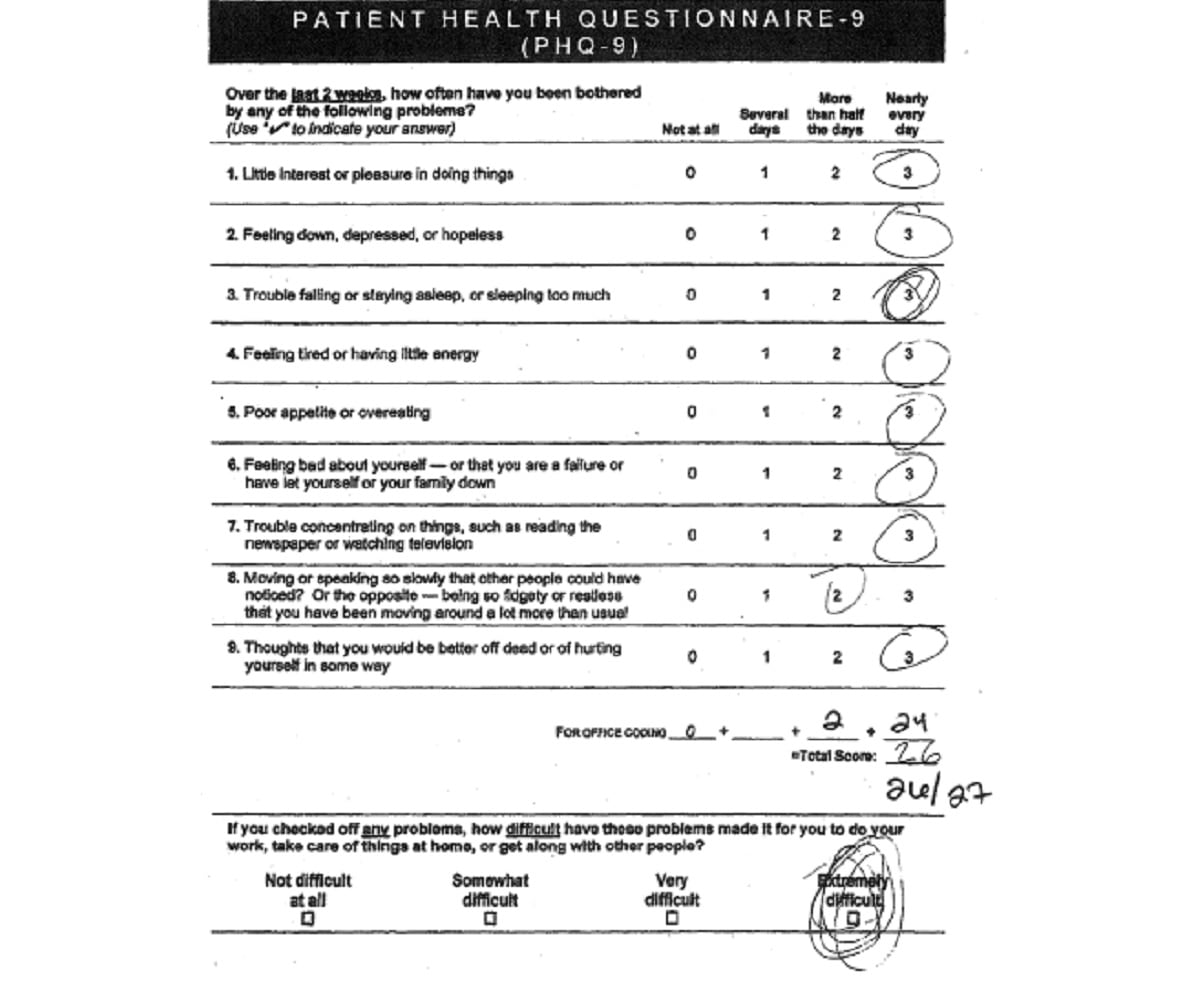

His intake form, included in military investigations, marked “no” for whether Hicks currently had suicidal thoughts, but it noted his past suicide attempt and that he was being treated for behavioral health issues.

Hicks appeared sad and indifferent, according to those records, and softly mumbled that he was getting little sleep and grappling with anxiety, depression, dread, despair, low self-worth, tension and rage.

On a scale of 1 to 3, Hicks circled 3 in response to a question about whether he had thoughts that he would be better off dead in the past two weeks.

Haggardly circled multiple times, Hicks marked that his problems made it “extremely difficult” for him to function.

While jail staff told authorities that Hicks did not say he was suicidal during his intake — a point disputed by Navy escorts — the Army’s 15-6 notes that “confinement can be a triggering event, and aggravate latent behavioral health issues or suicidal ideation.”

The next day, Feb. 8, Hicks was assessed by a medical officer who noted the sailor’s behavioral health history and past suicide attempts, the claim states.

That officer conveyed concerns about Hicks to the behavioral health team and recommended against moving him to general population until he received a full assessment, but did not order Hicks to be placed in a suicide watch protocol.

Later that day, Hicks was issued a belt.

While prisoners are only supposed to be able to draw belts and boot laces after being cleared by behavioral health, the Army’s investigation noted that the jail’s procedures were “unclear and confusing” on the matter.

The next day, Feb. 9, Hicks filled out paperwork and behavioral health questionnaires ahead of his Feb. 11 appointment where a specialist would determine if he could join the jail’s general population.

During a sick call visit for a cold on Feb. 10, a staffer wrote “that Prisoner Hicks is at an intermediate suicide risk based on his prior behavioral health history,” according to the 15-6.

A soldier tasked with tier checks in the early hours of Feb. 11 reported that Hicks was “alive and well inside his cell.”

“Lights on” was called at 5 a.m. and the soldier reported seeing Hicks “in the right-hand corner of his cell … standing with his back facing the cell door and alive,” the claim recounts.

The soldier reported Hicks being in the same spot during the 5:38 a.m. tier check, but the claim alleges that it was “far more likely that Macoy had been deceased for some time and the guard did not notice.”

Hicks was found hanging at about 6 a.m., and a “code red” was called away in the jail.

‘A death sentence’

How Hicks was handled by the Navy and Army stands in stark contrast to best practices for dealing with people who are or have been suicidal in the past.

Restricting access to lethal means, such as a belt, “is a well-documented suicide prevention strategy,” according to Rajeev Ramchand, a senior behavioral scientist and co-director of Rand’s Epstein Family Veterans Policy Research Institute.

“Many criminal justice facilities try to minimize inmates’ access to materials and devices that could result in suicide,” he said.

Ramchand added that some people experience a higher risk for suicide when they are transitioned between sources of care, such as when the Navy handed Hicks over to the Army.

Hicks was laid to rest nearly two weeks after his death, on Feb. 23, 2019, at Albany Rural Cemetery, on a bitter and snowy day.

“The world was spinning around us, but we couldn’t hear a thing,” Michael Hicks recalled. “2019 is a blur.”

As they move forward from the loss of their son, the Hickses have started HicksStrong, a non-profit dedicated to helping servicemembers get connected with mental health resources.

“We are determined to help save other military members from the same neglect,” Michael Hicks said.

Nearly a year after filing their negligence claim to the Army and Navy, the Hickses and their attorneys say they are still waiting to learn when their case will be taken up and decided.

“It has been demoralizing, disheartening and painful beyond words,” Michael Hicks said. “And yet, I will gladly walk through the fires of hell until our voice and Macoy’s story are heard.”

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call 1-800-273-8255 or text 838255 for 24/7 assistance. Responders are also available at veteranscrisisline.net.

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.