Alleged arson by a junior sailor started the fire aboard the amphibious assault ship Bonhomme Richard last summer, but a botched response at all levels of the Navy ultimately killed the once-mighty amphib.

That’s the main finding of a command investigation into the July 2020 mishap, obtained Tuesday by Navy Times.

“Repeated failures” at all levels hindered the firefighting response and led to the $1.2 billion ship’s destruction, according to the investigation, first reported on by USNI News.

Investigators found four main failure areas.

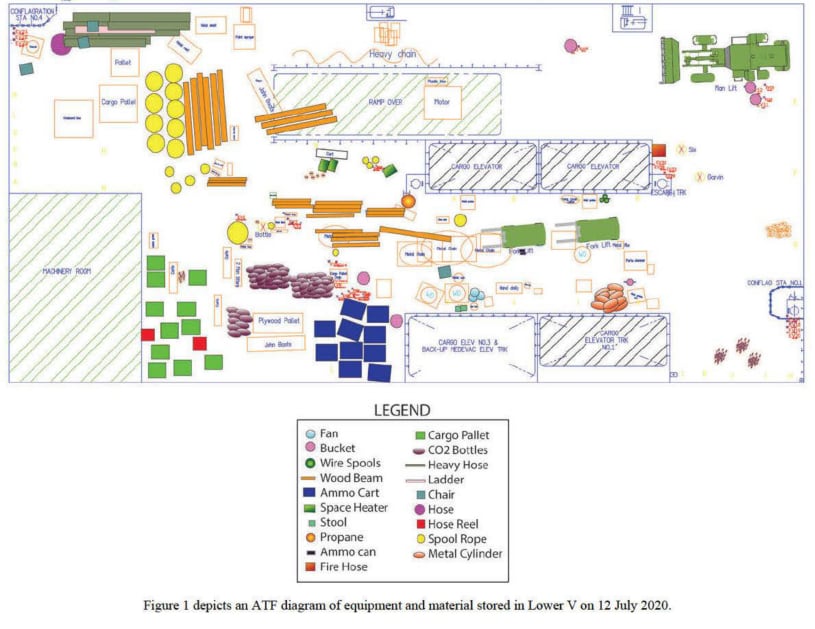

Bonhomme Richard was in the 19th month of a costly upgrade to accommodate the next-generation F-35C fighter jet, and this availability left the ship “significantly degraded” when it came to heat detection, communications and shipboard firefighting systems, while also producing a surfeit of combustible maintenance clutter as well.

RELATED

Roughly 87 percent of the ship’s fire stations were out of commission at the time of the July 12 blaze, according to the investigation.

At the same time, the probe found Bonhomme Richard’s crew wasn’t ready for such a fire.

The ship’s force’s training and readiness was plagued by “a pattern of failed drills, minimal crew participation, an absence of basic knowledge on firefighting in an industrial environment and unfamiliarity on how to integrate supporting civilian firefighters,” the report states.

“The crew had failed to meet the time standard for applying firefighting agent on the seat of the fire on 14 consecutive occasions leading up to July 12, 2020,” according to the report.

Ashore, Naval Base San Diego had failed to ensure its civilian firefighters were familiar with ships docked at the installation, nor did they practice how to support the ship’s force or integrate civilian resources in the event of such an emergency.

Southwest Regional Maintenance Center also didn’t communicate the fire risks to such a ship during maintenance and facilitated “unmitigated deviations from technical directives.”

Higher-level commanders failed to provide effective oversight, and an absence of delineated codes and responsibilities regarding that oversight also hindered the response.

Unifying these four failures “was a lack of familiarity with key policies and requirements,” as well as noncompliance at all levels.

“An example of how these focus areas combined to result in unacceptable levels of risk is the status of the ship’s Aqueous Film Forming Foam sprinkling system,” the report states. “At no point in the firefighting effort was it used — in part because maintenance was not properly performed to keep it ready and in part because the crew lacked familiarity with capability and availability.”

The investigation also found that a raft of systemic reforms put in place following a 2012 shipyard fire that destroyed the submarine Miami were not followed, helping fuel Bonhomme Richard’s demise in the process.

RELATED

The investigation recommends that disciplinary action be considered for 36 Navy leaders, including Bonhomme Richard’s commanding officer, Capt. Gregory Thoroman, its executive officer, Capt. Michael Ray, and Command Master Chief Jose Hernandez.

Several flag officers are also recommended for potential discipline, including the head of Naval Surface Force Pacific, Vice Adm. Richard Brown, and the leader of Navy Region Southwest, Rear Adm. Bette Bolivar.

Any administrative or disciplinary actions will be decided by the head of U.S. Pacific Fleet, Adm. Samuel Paparo.

The Navy has not yet laid out a timeline for those decisions.

“No single failure resulted in the loss of the ship, and thus accountability is not focused on any one individual, but rather shared across various Commanders, Commanding Officers and subordinate personnel,” the report states.

The investigation also lays out in grim detail how the fire started and spread, and how missteps at nearly every stage made things worse.

The Navy has charged Seaman Apprentice Ryan Sawyer Mays with starting the fire in the ship’s Lower V area on the morning of July 12.

A preliminary Article 32 hearing to determine whether Mays should go to court-martial is scheduled for next month, though Navy officials have refused to release a copy of his charge sheet.

Mays’ civilian attorney says his client is innocent.

Either way, the ship was particularly vulnerable to fire at that point.

Systems were tagged out for maintenance, scaffolding and other contractor detritus hung throughout the ship, and ship gear and other combustible material was “packed into various spaces,” even as more than 75 percent of the ship’s firefighting equipment “was in an unknown status.”

A lack of urgency

Just after 8 a.m., a sailor passed the ramp down to the Lower V and later told investigators it looked “foggy.”

She bought a snack from the vending machine and noticed a “hazy, white fog” coming from the Lower V.

“Because she did not smell smoke, (the sailor) continued to her berthing,” the report states.

After the smoke was reported, it took the command duty officer at least 10 minutes to call the fire away.

It was his first day in the position, the report states.

“Precious early minutes” to contain the fire were lost for several reasons, including the fact that duty sailors used their personal phones to communicate since they lacked radios, and the officer of the deck, or OOD, ordered further investigation of the smoke before taking any action.

The OOD directed damage control to call the fire away, but the 1 Main Circuit ship intercom wasn’t working in many areas of the ship, including in damage control, “and there was a lack of urgency.”

The OOD told investigators he delayed calling away the fire due to the possibility that there was a “benign reason” for the smoke, such as starting the emergency diesel generator.

Other first responders reported they were trained to not call a casualty away until they had put “eyes on” it.

When the ship’s first responders headed into the Lower V, no one was on the same page regarding which firefighting assets were online and available, contributing to their failure to try to extinguish the nascent blaze or set fire boundaries . This allowed the blaze to intensify.

As the fire grew and “a small number” of BHR sailors attempted their initial response, rescue and assistance teams from other ships on the waterfront began arriving but weren’t put to use by the Bonhomme Richard’s crew.

The ship’s initial firefighting crew struggled to find a usable fire hose, and the nearest fire stations had cut or missing hoses, which would have been spotted earlier if appropriate maintenance checks had been conducted, the report states.

“These teams were unsuccessful in locating a serviceable fire station and hose and they did not adapt their strategy in light of these conditions,” the report states.

Lack of direction

About half an hour later, at 8:30 a.m., the base’s firefighters arrived on scene and were met by the duty officer, who was overseeing “a small and unorganized group of Bonhomme Richard sailors.”

The base firefighters set about doing their own thing and pulled hoses nearly 30 feet up to the port aircraft elevator and into the hangar, even though a nearby side port door would have given them immediate access to the growing blaze.

“The lack of direction and leadership from Ship’s Force over firefighting efforts led (base firefighters) to operate as an independent unit,” the report states.

The lack of a hydrant on the pier led those federal firefighters to connect their hoses to a potable water riser that was supplying water to the adjacent warship Fitzgerald, and a team partially accessed the Lower V.

RELATED

“While this was the first attempt to deploy agent on the fire, nearly an hour after ignition, the hose team only opened their hose nozzle temporarily for cooling purposes,” the report states. “Within just a few minutes, the team backed out after one of the firefighters received a ‘low air’ alarm on his (breathing apparatus) and no relief team replaced them. "

Just more than an hour after the fire was called away, Bonhomme Richard’s commanding officer, Thoroman, arrived on scene.

By this point, the base firefighters were attacking the fire from the hangar and the San Diego Fire Department was on scene.

But a lack of compatible radios hindered the ability of the base and city firefighters to unify their efforts.

“Throughout the first three hours and with rare exception, there were no attempts by the CO, CDO or other Bonhomme Richard leaders to integrate civilian firefighters with Ship’s Force,” the report states. “Many of the personnel on scene at this time perceived that (base firefighters) had assumed control of firefighting.”

Base firefighters also reported that their hose fittings aren’t compatible with those aboard Navy ships.

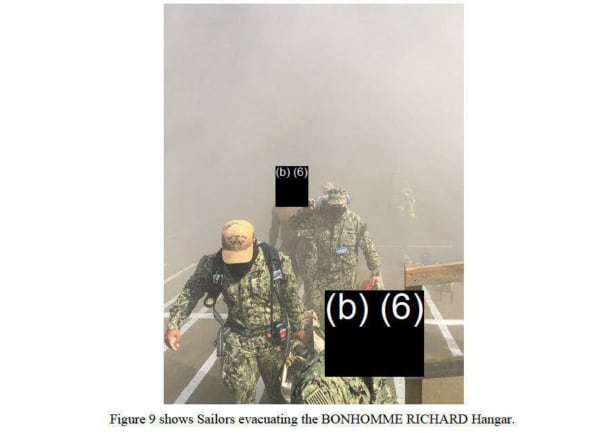

The CO ordered an evacuation for those without breathing apparatuses at 9:15 a.m.

But he did this by informing such sailors “individually in the Hangar because he did not have adequate communications gear,” the report states. “With a significant number of uniform personnel egressing the ship following this order, by 0930, all Bonhomme Richard personnel began to evacuate.”

One sailor, who wasn’t wearing a breathing apparatus, spent 15 minutes making sure the berthings were cleared and then fainted as she moved toward the hanger.

“An unknown sailor picked her up and carried her,” the report states.

Bonhomme Richard sailors would later report they assumed the base firefighters were in charge of the effort, and for the remainder of that first morning, “no hose teams comprised of Bonhomme Richard sailors attempted to descend to Lower V once (base firefighters) commenced their descent.”

Lack of preparation

Base firefighters later conceded that much time was wasted searching for the fire, and that the department doesn’t train personnel to search out a shipboard fire.

Just three months before the fire, Bonhomme Richard had been ordered to get its shipboard firefighting systems up to scratch when it onloaded nearly 1 million gallons of fuel, according to the report, but only “a limited” portion of the sprinkling systems were brought back online.

But even those systems brought online “had numerous undocumented system discrepancies,” the report states.

At about 9:45 a.m., nearly two hours after the fire was called away, power was cut to the ship, likely by the command duty officer who believed the fire was electrical.

But this move also cut power to the ship’s onboard firefighting systems.

“From this point on, all firefighting efforts relied on external water sources, which were further hampered by the lack of a fire main on (Naval Base San Diego) piers,” the report states.

Sailors later told investigators that efforts to contain the fire were hampered because doors and hatches had maintenance cables running through them, and that the fire spread too fast to set effective boundaries.

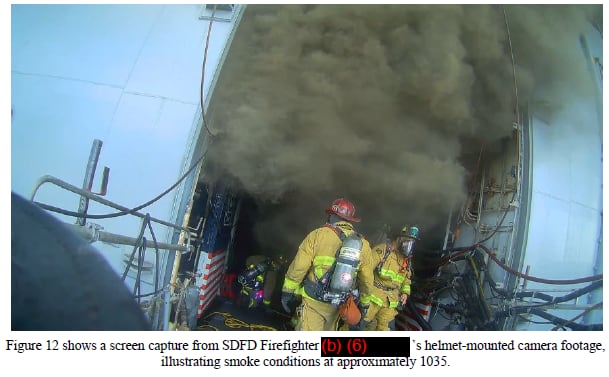

At about 9:35 a.m., San Diego Fire Department crews tried to enter the ship via a side door that was the closest access point to the seat of the fire.

But without assistance from the ship’s crew, they walked right into a pathway partially blocked by ship and contractor equipment.

Wires and “fallen temporary services” would prove to be a danger for firefighters throughout the effort, with one firefighter describing the ship as an “entanglement nightmare.”

By this time, combustible material in the Upper V had caught fire from heat radiating up from the deck below, which sparked more fires.

San Diego crews descended a ramp into the Lower V, “but the heat, lack of visibility and unfamiliarity with the ship’s layout led them to back out without engaging the fire,” the report states.

A series of explosions

Just after 10:30 a.m., San Diego and base firefighting leaders saw that conditions were getting bad and ordered their teams off the ship, “a decision likely preventing any loss of life or serious injuries to numerous personnel.”

Twenty minutes later, less than five minutes after the last firefighter got off the ship, a massive explosion caused by accumulated smoke rocked the ship, sending debris across the pier and knocking down firefighters and sailors.

“This explosion occurred after more than two hours of efforts where none of the ship’s installed firefighting systems were employed and no effective action was taken by any organization involved to limit the spread of the smoke and fires,” the report states. “After the explosion, all personnel completely evacuated the pier.”

The explosion caused the mess decks above to collapse into the Upper V.

With no firefighters on board, without electrical power or shipboard firefighting systems, the Bonhomme Richard blaze grew into a massive conflagration.

Crews relied “on ad hoc strategies” as they attempted to regain a foothold on the ship, and too little firefighting agent was laid down to combat the fire’s spread, according to the report.

Once the fire spread beyond the Lower V, any chance to douse the seat of the fire was lost.

“At some point during the afternoon, the fire reached 55-gallon drums of oil stored in Upper V and oxygen tank cylinders laid on the deck in the medical compartments,” the repot states. “As these items ignited, they caused minor explosions and accelerated the spread of the fire.”

Around noon, a San Diego assistant fire chief told Navy and base firefighting officials that his crews would not go back aboard Bonhomme Richard due to the risk and the fact there was nobody trapped onboard.

This angered the Navy and base officials, who told the San Diego team they could leave if they weren’t willing to get back onboard and fight the fire.

The San Diego Fire Department soon left the scene.

Early that evening, crews were trying to ascend the Upper V ramp when a jet fuel pipe exploded and created a “large fireball.”

The resultant explosion hit the crew and caused minor concussions “and blast-type injuries,” prompting another evacuation and halting of the firefighting effort.

That night, crews with Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron 3 began dropping water buckets on the burning ship, a mission made doubly dangerous by the need for them to get close to the fire while avoiding the deteriorating superstructure and antennas.

‘A command-and-control vacuum’

The world watched as the fire expanded and burned for the next four days, fouling the air and adding another black eye to the Navy’s surface fleet following the fatal ship collisions of 2017.

Some compartments reached temperatures of more than 1,200 degrees, and the ship’s aluminum superstructure interior liquified into molten metal that dripped into lower spaces.

“It was into this environment Sailors and firefighters made repeated entries in an attempt to save Bonhomme Richard,” the report states. “Though their efforts were unsuccessful and occurred beyond the point where the ship could have been saved, the courage displayed in subsequent firefighting efforts warrant acknowledgement.”

While the command and control for the firefight was “initially chaotic,” it improved over time, although the ship’s leadership failed to take command of the situation or integrate the firefighting efforts.

Instead, the head of Expeditionary Strike Group 3, Rear Adm. Philip Sobeck, the ship’s operational commander, stepped in to fill “a command-and-control vacuum,” an initiative the report credits for the fire eventually being put out on the fifth day.

Firefighting efforts were eventually helped along by the fact that the inferno didn’t have any more shipboard combustibles to consume.

“The fire left the ship damaged beyond economical repair, leading to the decision to decommission Bonhomme Richard,” the report states.

The ship was sold for less than $4 million earlier this year and sent to a Texas shipbreaker for dismantling, USNI News reported this spring.

‘Multiple execution failures’

The report notes that the risk of shipboard fire is much greater when in the yards for maintenance, due to industrial hazards.

And while the buck stops with the ship’s CO and crew, the report notes that other organizations failed to offer Bonhomme Richard support.

The Southwest Regional Maintenance Center oversees such maintenance periods, and Naval Base San Diego was responsible for ensuring the ship had readily available firefighting capabilities if needed.

Higher-level commanders were supposed to ensure compliance and provide oversight.

“Instead, there were multiple execution failures throughout the maintenance period, which are shared by Ship’s Force and the supporting organizations,” the report states.

The framework for how to conduct safe and fire-free maintenance availabilities was most recently reformed less than a decade ago, after the fire aboard the submarine Miami destroyed the boat in May 2012.

A main takeaway from the Miami probe was that prior to that blaze, a lower level of fire safety during maintenance periods had been deemed acceptable. That fire led to reforms aimed at preventing an outcome like the Bonhomme Richard.

But many of the requirements developed after the Miami mishap weren’t followed during Bonhomme Richard’s availability, including drills that would allow a coordinated response to such a fire.

Such policy changes were “inconsistently implemented” across Navy maintenance in the past five years, according to the report, and organizations including Naval Sea Systems Command, Navy Installations Command and Naval Surface Force Pacific failed to comply or provide oversight.

“This placed the non-nuclear Surface Fleet on a trajectory of an unacceptable fire prevention and response posture with a high level of accumulated risk before the fire started on 12 July 2020,” the report states. “Once the fire started, the response effort was placed in the hands of inadequately trained and drilled personnel from a disparate set of uncoordinated organizations that had not fully exercised together and were unfamiliar with basic issues.”

While noting that Navy leaders operate “in a pressurized environment, with aggressive timelines,” the report slams involved leaders for shorting safety and standards in order to meet such timelines.

“Exacerbating this, leaders failed to communicate these choices up the chain of command,” the report states. “Commanders at all levels are entrusted with extraordinary responsibility with full regard for its consequences — as command is the foundation upon which our Navy rests.”

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.