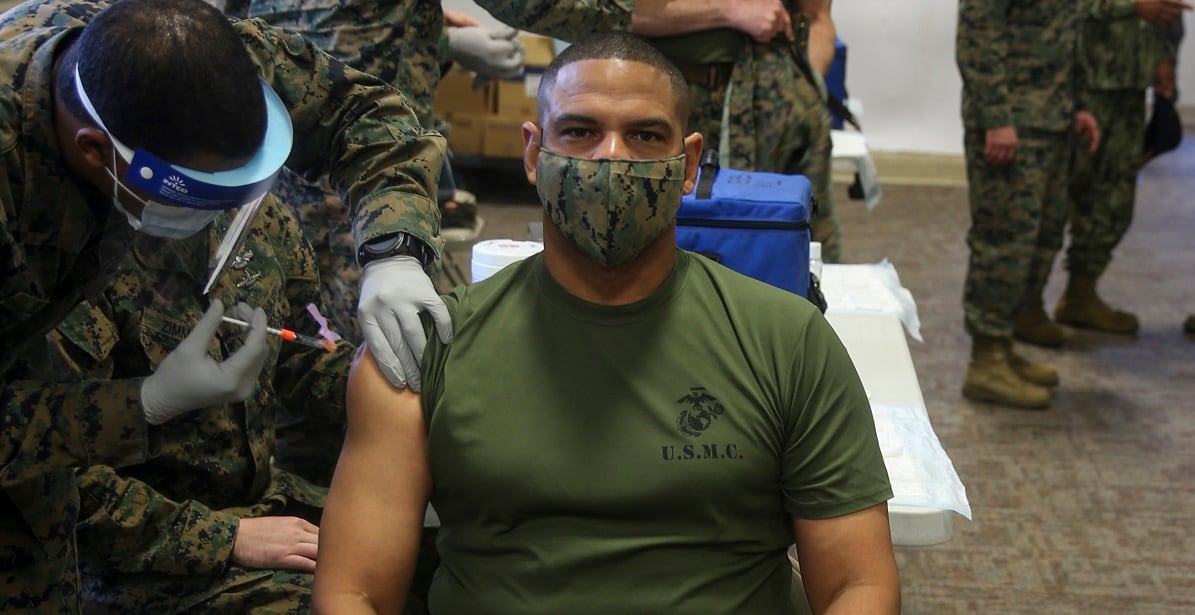

An ongoing legal battle over whether the military can force troops to get vaccinated against COVID-19 has left the Navy with a warship they say they can’t deploy because it is commanded by an officer they cannot fire.

It’s a standoff the brass are calling a “manifest national security concern,” according to recent federal court filings.

The issues stem from a lawsuit filed in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida late last year alleging servicemembers’ rights are being infringed upon by the COVID vaccine mandate because their religious beliefs prevent them from taking the vaccine.

Judge Steven D. Merryday issue an order last month banning the Navy and Marine Corps from taking any disciplinary action against the unnamed Navy warship commander and a Marine Corps lieutenant colonel for refusing the vaccine.

In the process, the case has raised questions about the lines between military good order and discipline, and the legal rights of servicemembers as American citizens.

Merryday’s injunction is “an extraordinary intrusion upon the inner workings of the military” and has essentially left the Navy short a warship, according to a Feb. 28 filing by the government.

RELATED

“With respect to Navy Commander, the Navy has lost confidence in his ability to lead and will not deploy the warship with him in command,” the filing states.

The Navy has 68 Arleigh Burke-class destroyers in the surface fleet, 24 of which are based in Norfolk.

But while the government’s filing framed the judge’s order and the commander’s vaccine refusal as impacting the core of American military might, plaintiffs’ attorneys contend the case is ultimately about the rights afforded the plaintiffs under the Constitution and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. That act bans the government from substantially burdening a person’s exercise of religion.

Navy officials declined to comment on the case or identify the commander or the ship he leads, but court records show the commander works for Capt. Frank Brandon, the commodore of the Norfolk-based Destroyer Squadron 26.

COVID commander

The Feb. 28 filing alleges that the commander has already disregarded Navy regulations after he “exposed dozens of his crew to COVID-19 when he decided not to test himself after experiencing symptoms.”

A declaration filed in early February by Brandon states he visited the Navy commander aboard his ship in November and that the ship CO “could barely speak.”

After a briefing involving dozens of sailors in close quarters on the ship, the Navy commander admitted to his boss that he had a sore throat.

Brandon ordered him to get a COVID test, and the commander tested positive after telling his boss he had discussed his illness earlier with the ship’s corpsman, according to the declaration.

The government’s Feb. 28 filing also argued that, even if the court found the CO credible, he can’t lead and crew a warship “given the breach of the relationships with both his commanding officer and his subordinates.”

A commanding officer can’t enforce orders to his 320-sailor crew if he does not abide by those orders himself, the filing argues.

RELATED

“By forcing the Navy to keep in place a commander of a destroyer who has lost the trust of his superior officers and the Navy at large, this Order effectively places a multi-billion-dollar guided missile destroyer out of commission,” defense attorneys wrote.

A Marine Corps lieutenant colonel tapped to lead a combat logistics battalion puts that service in the same boat, as “failure to follow the lawful policies and standards of her superiors undermines her ability to require her subordinates to follow her policies and standards,” the filing argues.

“No military can successfully function where courts allow service members to define the terms of their own military service, including which orders they will choose to follow,” the filing states.

Government overreach?

But according to Mat Staver of the Liberty Counsel, a religious freedom non-profit representing the plaintiffs, the government is “putting in these histrionic kinds of statements into the record that are completely contrary to the evidence.”

While Navy leaders have professed lost confidence in the CO, they still sent him and his ship out to sea for two weeks of training, Staver told Navy Times on Monday.

“When this was filed in court saying the ship is not deployable because they lost confidence in the Commander, the Commander was on board the ship out to sea for two weeks of testing and training for military readiness,” Staver said. “He returned to port last Friday, March 4, after the drills were completed.”

The government’s insistence that the Navy commander can’t command his ship “reeks of petty retaliation and contempt” of the court’s preliminary injunction banning such retaliation, the plaintiffs’ attorneys wrote in a March 1 filing.

RELATED

“The Navy’s feigned ‘loss of confidence’ in the Commander is patently pretextual and has everything to do with the Commander’s lawful and orderly attempt to obtain judicial relief from an unconstitutional mandate,” the filing states.

The ship was underway for more than 300 days during the 400 pandemic days when no vaccine was available, the plaintiffs contend, “with no operational impediment.”

“If there is injury to the Navy from shutting down the Commander’s ship, it is self-inflicted and intentional,” the filing states.

Good order and discipline

In a statement attached to the Feb. 28 filing, Vice Adm. Daniel Dwyer, the head of U.S. 2nd Fleet, called the temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction in the case “profoundly concerning.”

“The prospect of a subordinate commander in charge of other Service members or military assets disregarding the orders of his or her superior for personal reasons, whatever they may be, is itself a manifest national security concern,” Dwyer wrote.

The judge’s order also “creates a health risk to personnel” assigned to the commander’s ship, according to Dwyer.

Such an order is a threat to the foundation upon which the military stands, according to the vice admiral.

“It shields Navy Commander from the responsibility and accountability upon which his command authority rests and leaves him in charge of enforcing policies from which he is immunized,” according to Dwyer.

The Marine Corps lieutenant colonel selected to command a combat logistics battalion presents a similarly difficult situation for that service, the head of II Marine Expeditionary Force, Lt. Gen. William Jurney, wrote in the same filing.

“The Court’s injunction, which prevents the Marine Corps from removing Lt. Col. 2′s command selection, will have immediate and irreparable effects on the training pipeline and slating process for prospective commanders,” Jurney wrote.

Other Navy leaders, including Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Mike Gilday and Fleet Forces Command’s leader, Adm. Daryl Caudle, also filed statements in support of the Feb. 28 filing.

As the plaintiffs and their attorneys seek to turn the lawsuit into a class-action case, which could see the injunction expand from 35 personnel to “potentially 2,500 to 4,000 personnel across various ranks, occupational specialties and unit assignments,” Caudle wrote.

“In the deadly business of protecting our national security, we cannot have a Sailor who disobeys a lawful order to receive a vaccine because they harbor a personal objection any more than we can have a Sailor who disobeys the technical manual for operation a nuclear reactor because he or she believes they know better,” he wrote.

The Feb. 28 filing notes how the close quarters of a ship are prime places for COVID to spread, and that the court’s injunction exceeds its authority.

“Courts have consistently held that decisions as to who is placed in command of our troops are beyond the judiciary’s competence and constitutionally entrusted to the military and political branches,” the filing states.

Government’s burden of proof

But Judge Merryday denied the government’s request in a March 3 decision and accused the defense of attempting “to evoke the frightening prospect of a dire national emergency resulting from allegedly reckless and unlawful overreaching by the district judge.”

RELATED

Merryday accused the defense of arguing as if the Religious Freedom Reform Act doesn’t apply to military members.

The commander’s contention that his rights under the act were denied “demands a closer examination, which is readily and reasonably promptly available.”

“Surely the free exercise rights restored by RFRA are not subject to evisceration or circumnavigation by a notion as subjective and illusory—and, according to the defendants, unreviewable by the judiciary — as a sudden ‘loss of confidence’ by a superior officer who sends a declaration to the court,” Merryday wrote.

What’s more, the government’s contention that vaccination against COVID maximizes the health and safety of servicemembers is not in dispute, he wrote.

“The defendants might prefer to argue that question, but the plaintiffs and the court address only the question presented in the RFRA claim,” Merryday’s order states.

Rather, the question is whether vaccinating the Navy commander and Marine Corps lieutenant colonel over their religious objections is “the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling government interest.”

“RFRA establishes that explicit test and places the burden of proof on the government,” Merryday wrote. “Proving the obvious, that vaccination is best for ‘the force’ and necessary for ‘the force,’ fails to satisfy the ‘to the person’ test require by RFRA. The military designs to avoid the ‘to the person’ test, but the statute is unflinching.”

In denying the government’s Feb. 28 motion, Merryday gave both sides until Tuesday to submit a witness and exhibit list as the case continues.

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.