These days, retired Navy Capt. Brett Crozier comes across as a man who accepts the decisions he made to save his sailors in 2020, ending his military career in the process.

Crozier knew the possible consequences of sending that March 2020 email from Guam to higher-ups while he was commanding the COVID-stricken aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt, a message in which he begged Big Navy to speed up its efforts to get his sailors off the ship during those uncertain early days of the pandemic.

“We are not at war. Sailors do not need to die,” Crozier wrote in the message. “If we do not act now, we are failing to properly take care of our most trusted asset — our Sailors.”

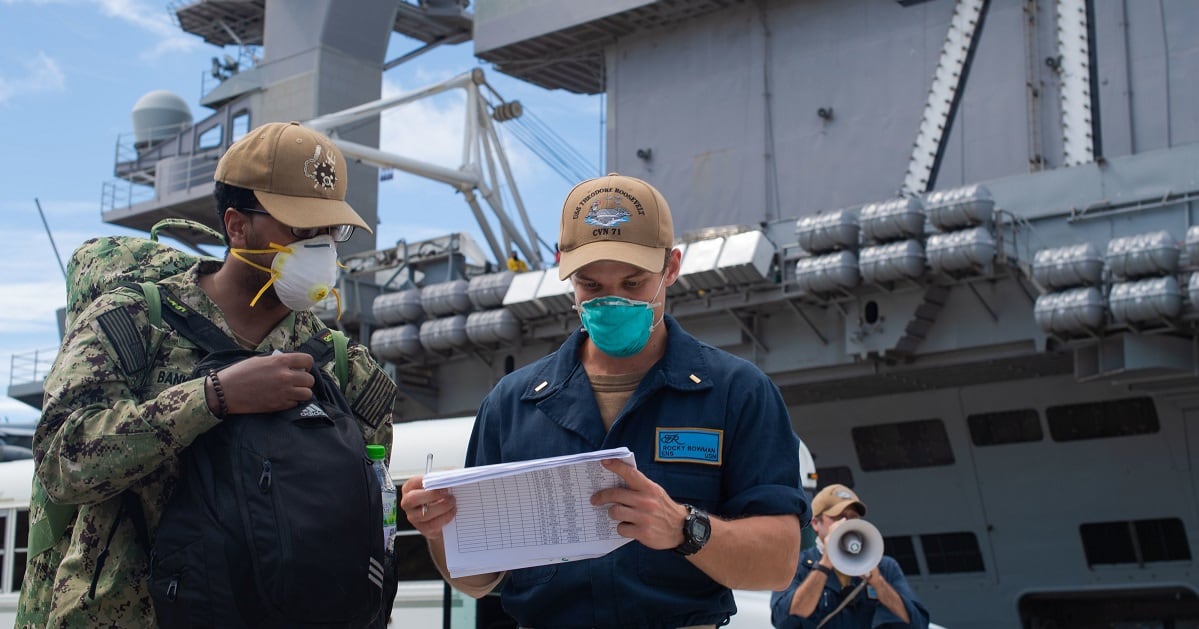

After that letter leaked to the San Francisco Chronicle, he accepted being fired in April 2020, even as public outrage over Crozier’s concerns spurred the Navy into faster action, securing off-ship rooms for the 5,000 embarked TR sailors sidelined on the Pacific island.

A few months after his firing, Crozier’s ultimate goal came to fruition: From atop a paddleboard near San Diego, Crozier watched the TR and nearly all its sailors get home safely from their so-called “COVID cruise.”

RELATED

Crozier, a helicopter and jet pilot before commanding TR, retired from the Navy last year and has largely remained out of the spotlight.

But this week, he has a book coming out that for the first time offers his perspective on leading the carrier crew during its battle with COVID and what he learned from the experience.

“Surf When You Can: Lessons in Life, Loyalty and Leadership from a Maverick Navy Captain” chronicles not only his time aboard TR, but includes tales from his long and varied career.

Crozier recently spoke with Navy Times about the TR, COVID and the Vietnam port call that preceded it. He also talked about standing up for sailors and whether he has any lingering beef with former acting Navy Secretary Thomas Modly, who slammed him in an address to the TR’s crew just days after Crozier was relieved of command.

RELATED

This conversation has been edited for length, clarity and grammar.

Q: Tell us a bit about why you decided to write this book?

A: “I think it came down to three reasons. One was to recognize all the men and women I had the privilege to serve with and sail with and fly with during my 30-year career.

I also wanted to share with a broader audience the things that I learned during those 30 years. We all have stories to tell and sea stories, but I thought I had the privilege of an incredible career and learned from a lot of people.

Third, and I think this is important, it was to kind of dispel the myth that I was bitter, or that I was disgruntled and leaving the military in a different state than I was.

The TR episode is what it is and we can talk more about it, but at the end of the day, I served 30 years in the military and I enjoyed everything about it.

Those events happened, that’s part of life and COVID threw some curveballs to everybody across the world. And no matter how it came out in the end, the Navy was pretty good to me. I came back to San Diego, I had a great job, an important job. I still got to fly the F/A-18 Super Hornet up until the month before I retired.

So, I felt really honored in the end, particularly with naval aviation, they took really good care of me and my family, and I’m honored to have served 30 years without any kind of anger or malice.”

RELATED

Q: The book lays out the varied career you had, from piloting helicopters to the time you spent on a seized dhow in the Middle East and onto your career as a fighter pilot, not to mention the years-long education that led to you commanding a carrier.

You sound pretty at peace with what went down. Was that a process for you? Was it difficult to have your entire service encapsulated by an event that was largely beyond your control, namely the pandemic, and how did you work through that?

A: “Great question. I will tell you that I was never really bitter. I mean, I disagreed with the decision, but to go back to the moment that I sent the red flare as we say, I really had made peace with whatever the outcome was going to be at that point.

It was so important for me to make sure that I was removing all barriers (to getting sailors off the TR in Guam). To me there was no question about what I needed to do to make sure they were getting the best care possible.

And I knew I was going to rock the boat in doing so.

So, when the boat rocked, there was a reaction that maybe I didn’t predict, but I knew there would be a reaction and I knew it was going to have implications to my career. And I was really at peace from the moment I sent the email asking for help. If it worked out that I stayed in command, that’s great, and if it didn’t, that was the decision the Navy was going to have to make for the organization at large.

My focus was the sailors under my command and the entire crew of 5,000 aboard the TR. For me, it was pretty easy.”

Q: One of the most iconic moments of the whole TR saga was when you left the ship in early April after being relieved and you walked off the ship and down the enlisted brow for the last time. You recounted it in the book. We wrote about it. A couple of TR sailors recorded it, so we could all see that moment.

In the hangar, scores of TR sailors chanted “Captain Crozier” as you walked off the ship for the last time. Did you know that the crew was gathering to see you off like that? And what did that goodbye mean to you?

A: “I had no idea. In fact, it took me the better part of the day to pack up and make sure I was ready to leave the ship. I had been told to leave the ship by the end of the day. And so I spent the better part of the day talking to folks and making sure the ship was going to be in good hands and talking to my XO, making sure he knew what he needed to know. And packing a lot of boxes. That’s like the 21st move in my career. It was a quick pack out.

So, when it came time to leave the ship, the duty officer offered to open back up the officer brow. We normally keep the officer brow closed after 1800. But (to reopen the officer’s brow), you have to stand the watches back up, you have to put the officer of the deck, put a couple watch standers, open the brow.

And the last thing I wanted to do was impact people and make them have to go stand an extra watch. And so I said I’m fine, I’m more than comfortable going off the enlisted brow and not having to make anybody go out of their way to do anything special for my departure.

I had no idea until I stepped in the hangar and saw them gather and start chanting and saying goodbye.

That was the first time, in that moment or at least that day, that it all kind of hit me, the gravity of the situation. What I thought could happen after I sent the email had come to fruition.

I was taken aback because of the number of sailors that had gathered to provide that sendoff.

I saw two things. One was thank you for sending the email, bringing attention to what had been a growing problem on the ship and what they had been concerned with. I think they appreciated me stepping up and risking my career to do that.

And here I am leaving as they are approaching what is going to be a fight. As they figure out how to battle COVID and to get back to sea, and now I’m leaving them at that moment. I felt bad.

But I felt like they weren’t going to give up. They weren’t despondent. They were like, ‘we’re going to fight on and we’re going to fight on for you because this is an important fight ahead.’

Those are the two big things I took, I guess, as I tried to take it all in and then left the ship for the last time.”

Q: There was reporting in the spring of 2020 that leadership was considering reinstating you as CO of the TR. But, after an investigation, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Mike Gilday held a press conference that summer to announce that you would not be returning.

Speaking of you and the carrier strike group commander, Rear Adm. Stuart Baker, Gilday said, “they did not do enough, soon enough, to fulfill their primary obligations, and they did not effectively carry out their guidelines.”

According to Gilday, the wheels were already in motion to secure beds for TR sailors in Guam when you sent the red flag email that started it all. What do you say to those claims?

A: “I guess I fundamentally disagree.

I don’t think there was anyone that had any ill will for the crew. I think we were more deliberate in the planning process than we needed to be, and we needed to be quicker. I was arguing, ultimately, that we needed to make a decision that was quicker.

So yeah, I’m sure there were things in motion, I know there were. But at the end of the day, some of the other ones we didn’t execute were slowing down the process.”

Q: Is it accurate to say you were focused more on securing hotel rooms for everybody, as opposed to plans to house sailors in shared facilities, like a gymnasium, where COVID could spread further?

A: “We needed to use all of it. We knew that we weren’t going to have sufficient space on the base. So, we had to use a gym off base. And we needed to expand beyond what was available in those limited capacities.

And some of the larger facilities being offered were dirt-floored warehouses with a port-a-potty, and that was just going to be a worse condition.

We didn’t turn down a single option. I think that was one of the accusations, were you trying to hold off for this perfect solution? No. We were getting sailors off the ship as fast as we could, as fast as the base would allow it, and to put them in the spaces that were available.

RELATED

And then on top of that, we were trying to secure hotel rooms in addition to that, because we knew we didn’t have sufficient capacity on the base. If we pulled pierside and there was space for 4,000 on the base, well, that’s what we probably would have used. But that wasn’t the case. And we needed more space. So, we continued to push.

I think some of the criticism that we were holding out for this perfect solution is not accurate.

For us, knowing there were 10,000 empty hotel rooms (on Guam), that seemed like an easy, quick solution. And we just had to kind of figure out a break through the logjam. And that was beyond my capability.

It’s very political, too, because you’re talking about Guam. You’re talking with the governor of Guam and the governor has to make sure that, politically, it makes sense to the residents of Guam.

It was political assistance that we needed. And one of the impetuses behind the email was, let’s fight this at the right level.

I think we were learning as we went, and we were erring on the side of caution in all cases. And we were trying to get folks off the ship as quickly as we could.”

Q: In terms of the letter that leaked to the San Francisco Chronicle, your request for help that you sent to superiors. Did you want that letter leaked and did you know who leaked it? Do you think the leak got your sailors off the ship faster?

A: “I don’t know who leaked it. I knew that risk existed. I guess I accepted that risk because I also knew that we were pierside with 5,000 people with cellphones who were communicating back home very quickly.

There was this growing concern from the sailors. We had no doubt they were communicating home, because we were getting feedback from all the families back home as to what was going on and what we were doing, because they were hearing directly from their sailor.

The initial response that I got from the CNO, was, ‘hey, you know, this is exactly what we want a captain to do, is to raise the alarm and speak truth to power and be direct in the communication.’”

Q: Were you mad that it was leaked?

A: “I think I knew that it was going to change the dynamic a little bit. I knew there was going to now be additional outside influence from folks outside the military.

So, I don’t know that I was mad. I rolled with it. I knew that was the risk. And then I just was hoping that it wouldn’t detract from what I was ultimately trying to accomplish, which was to get them to care.

If you look at the public reaction, I think that helped influence the Navy’s reaction. It just made sure that that was the most viable and executed course of action, which is to put folks in hotels and speed up their departure from the ship.”

Q: The leaked letter, even if it sped up help for TR’s crew, cost you your job. But the fallout from it also cost then-acting Navy Secretary Thomas Modly his job. Shortly after you were fired in early April 2020, Modly flew to Guam and addressed the crew and slammed you in the process. When a recording of Modly’s address to the TR leaked, he was shown the door as well.

Have you ever spoken to him, and what is your opinion of Modly three years later?

A: “He was in a tough spot. I know he was doing all he could to help the situation, and I also know he was doing it at a different level, with different pressures that I could only imagine. He’s a former Navy helicopter pilot, a former Academy grad. And I know, ultimately, that what he wanted was what’s best for the crew.

I knew he didn’t want it as much as I did, and I knew that’s why it was incumbent upon me as the captain to take the action that I did. We spoke shortly after he arrived to Guam, when I was in quarantine, before I came back to San Diego. And we did have a pleasant conversation. He was under immense pressure at that point from all sides of the aisle and that’s not what I would want for anybody.

When I made the decision I did, I did it out of love for my crew. I think his decision to come out, but then also to get on the 1MC and kind of highlight his frustration, I think that decision was made out of frustration.

And I think that’s a lesson for all of us: If you make a decision out of frustration, it’s generally not going to go your way.

I know that we could probably share a beer together and talk over the story again, and we might just fundamentally disagree on how we would go back and handle it.

I do think he wanted what was best for the Navy and he worked really hard in his time as acting secretary. And I didn’t ever want to see his career end. I hope he’s doing well.”

Q: The book contains a great anecdote from July 2020 when the TR got back to San Diego. You had been reassigned to Naval Air Forces, but you got to witness your carrier returning with the entire crew intact, save for the loss of Chief Aviation Ordnanceman Charles Robert Thacker Jr., 41, the lone COVID casualty from the TR.

Can you walk us through watching TR return?

A: “An old buddy of mine, an old XO actually, he and I decided we were going to paddle out on standup paddleboards, just to kind of greet them. We went out, and from a safe distance, but close enough to see the ship and see the sailors and see their faces as they manned the rails in whites to come back. And it was a great moment.

It kind of closed out that story for me.

The whole reason I sent the email to my superiors was to try make sure we had exhausted all opportunities to take care of our sailors in that moment when we had COVID spreading pretty dramatically, with the intent of getting them healthy, getting them back on the ship and getting the ship back underway, so it could continue its mission.

So, to see it come back then, I guess that’s what I wanted all along, was just to make sure they made it back.

And they did amazing things. I think it’s worth pointing out, to go from a dormant state, a carrier pulls in, you have to sustain it pierside, you have to go through this battle with COVID.

Then you bring back everybody, and you have to get the aviators current again, there were some unique challenges in how they did that, and they pulled it off pretty well and they did it very safely.

Despite all the ups and down, all I ever wanted was for the ship to come back safely and pull back in.”

Q: Many of our readers feel that you were thrown under the bus for trying to do the right thing. Do you have any advice for a commander or a senior enlisted member who has similar feelings? How does one recover from such an experience and move on?

A: “Great question. I can only spend so much time worrying about what I can control, but I shouldn’t waste a lot of time worrying about what I can’t control.

People can be frustrated by how they feel they’ve been treated by the military. In many cases, they could be absolutely right. Decisions were made that were not made with the utmost fairness, and they were not made with consideration for the individual.

But, make no mistake, the senior folks in the military are going to make decisions based on what they think is best for the larger organization. I knew that was going to be the case for me and that’s how it kind of played out.

I think that when people feel like they’re thrown under the bus, they can certainly be frustrated, and they’re absolutely entitled to that. In some cases, maybe they don’t understand the bigger picture that is forcing those decisions taking place above them.

RELATED

I’m not discounting folks that feel frustrated when they are made to look like scapegoats. I think there’s probably some truth in some of that. I think sometimes it’s a damage-control measure by a large organization to try to move on with the mission and try to not have to dwell on it. Certainly, that probably played into my case a little bit.

At the end of the day, you can keep your head held high, knowing that you did the best you could for what you were entrusted to do.

In the end, I think they should all be proud of their service and understand that, while the Navy is not perfect, it’s still the best Navy in the world. And they should be proud to have served in some capacity, whether they made a career or not. Whether they served for a month or not.

It’s still an incredible organization that I stand behind.”

Q: TR had that port call in Da Nang, Vietnam, in March 2020. It was a big deal, just the second U.S. carrier to pull into the country in 40 years.

In the book, you touch on how this was not the best time to be pulling into Vietnam, given the growing pandemic. Looking back, was that port call a mistake? Do you believe that COVID entered your ships force there?

A: “We had all expressed our concerns prior to pulling into Vietnam. And we were tracking very closely what the government of Vietnam was putting out in terms of active cases across the country.

The Navy just didn’t have clarity, really, on how many cases were in Da Nang, because we were told none and certainly that was not the case. And I do think we probably, in all likelihood, picked it up there.

Remember where we were as a world at the time. The entire world was trying to figure out COVID, how it spread and how quickly it spread. And we didn’t have enough test kits anywhere, to include on the ship.

In hindsight, if we had not pulled in there, I think that would have mitigated most of that risk of exposure and maybe changed the story a little bit.”

Q: What’s next for you? Was retirement a difficult adjustment, not having to get up on time and put on a uniform and head in to work every day?

A: “You’re absolutely right. You wake up and you wonder what you should be doing. I made a point, in a pact with myself, that I was going to surf 30 straight days, rain or shine. And I surfed every day somewhere in San Diego, which was good. I needed it.

And now I am the chief operating officer for Veteran’s Village of San Diego. We’re a large Southern California nonprofit focused on helping homeless veterans, or veterans with mental health or substance abuse problems.

Anyone who leaves the military will tell you it doesn’t matter what you go do, there’s a change and a transition required, and I’m still figuring out what that means.

So, for me, it’s a good first step transition, I think, and it’s definitely allowed me to surf a bit more.”

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.