A growing number of aircraft and ships from the U.S. and Canada searched Tuesday for a submersible vessel carrying five people that disappeared on its way to the wreckage of the Titanic.

The U.S. Coast Guard is leading the search for the small craft, named Titan, in a remote area of the North Atlantic Ocean. OceanGate Expeditions, an undersea exploration company, has been chronicling the Titanic’s decay and the underwater ecosystem around it via yearly voyages since 2021.

What we know so far about the submersible, what may have happened, and what’s being done to find it:

When and where did the Titan disappear?

The craft submerged Sunday morning, and its support vessel lost contact with it about an hour and 45 minutes later, according to the Coast Guard.

The vessel was reported overdue about 435 miles (700 kilometers) south of St. John’s, Newfoundland, according to Canada’s Joint Rescue Coordination Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The Titan was launched from an icebreaker that was hired by OceanGate and formerly operated by the Canadian Coast Guard. The ship has ferried dozens of people and the submersible craft to the North Atlantic wreck site, where the Titan has made multiple dives.

The U.S. Coast Guard said Tuesday afternoon that the submersible had about 40 hours of oxygen remaining, meaning the supply could run out Thursday morning.

What is being done to find it?

At least 10,000 square miles (25,900 square kilometers) have been searched, according to the U.S. Coast Guard.

The Canadian research icebreaker Polar Prince, which was supporting the Titan, was conducting surface searches with help from a Canadian Boeing P-8 Poseidon reconnaissance aircraft, and the Canadian military dropped sonar buoys to listen for any possible sounds from the Titan.

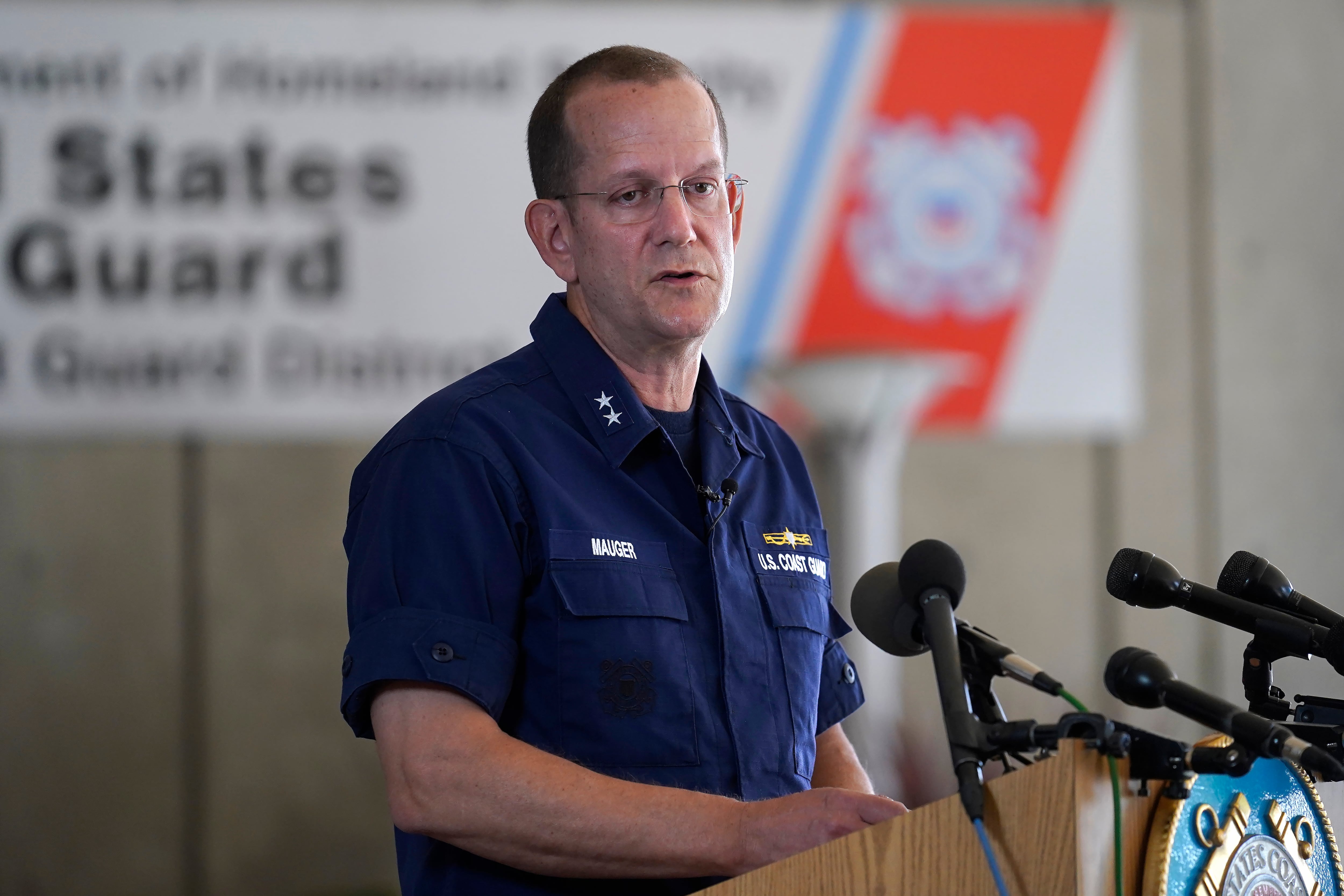

An underwater robot had also started searching in the vicinity of the Titanic, and there was a push to get salvage equipment to the scene in case the submersible is found, said Jamie Frederick of the First Coast Guard District in Boston.

Two U.S. Lockheed C-130 Hercules aircraft were conducting overflights, and three C-17s from U.S. Air Mobility Command have also been used to move another commercial company’s submersible and support equipment from Buffalo, New York, to St. John’s to aid in the search.

A Royal Canadian Navy ship that provides a medical team specializing in dive medicine and a six-person mobile hyperbaric recompression chamber also was en route Tuesday, according to the Canadian military.

What kind of deep-sea vessel is it?

OceanGate has described the Titan as “the largest of any deep diving submersible” with an “unparalleled safety feature” that assesses the integrity of the hull throughout every dive.

Made of titanium and filament wound carbon fiber, the Titan weighs 20,000 pounds (9,072 kilograms) in the air, but is ballasted to be neutrally buoyant once it reaches the seafloor, the company said.

Titan is capable of diving four kilometers (2.4 miles) “with a comfortable safety margin,” according to documents filed by the company in April with a U.S. District Court in Virginia that oversees Titanic matters.

At the time of the filing, Titan had undergone more than 50 test dives, including to the equivalent depth of the Titanic, in deep waters off the Bahamas and in a pressure chamber, the company said.

During its 2022 expedition, OceanGate reported that the submersible had a battery issue on its first dive and had to be manually attached to its lifting platform.

Greg Stone, a longtime ocean scientist based in California who has been on similar submersibles, said the vessels operate much like hot air balloons, with weights that pull it down. He said those onboard would have been briefed on how to bring the submersible back to the surface.

“It’s all about buoyancy,” he said. “It’s usually a few switches where you can throw them, and they’ll just release the weights on the outside of the submarine and it’ll come back up.”

What might have happened to it?

Eric Fusil, an associate professor and director of the shipbuilding hub at the University of Adelaide, described several possible scenarios, including a power blackout, fire, flood or entanglement.

A fire, he said, could incapacitate the vessel’s systems or create toxic fumes that could render the crew unconscious. A flood would be even more dramatic, resulting in a near instantaneous implosion.

The most optimistic scenario would be a power loss that allowed the vessel to return to the surface, where it would wait for search crews to find it, Fusil said.

“The takeaway is that it’s easier to go and rescue people in space than to dive that deep and rescue people because we can’t communicate easily,” he said. “It’s still a very, very risky endeavor, even with the technology of today.”