Today, March 25, we remember Medal of Honor recipients — the nearly 3,500 heroes who’ve received the nation’s highest award for valor.

Many of us recall famous names from that list like Joe Foss, James Bond Stockdale, Smedley Butler, Dan Daly, Lance Sijan and George “Bud” Day. Thomas Hudner, who passed away Nov. 13 at age 93, was a lesser-known recipient.

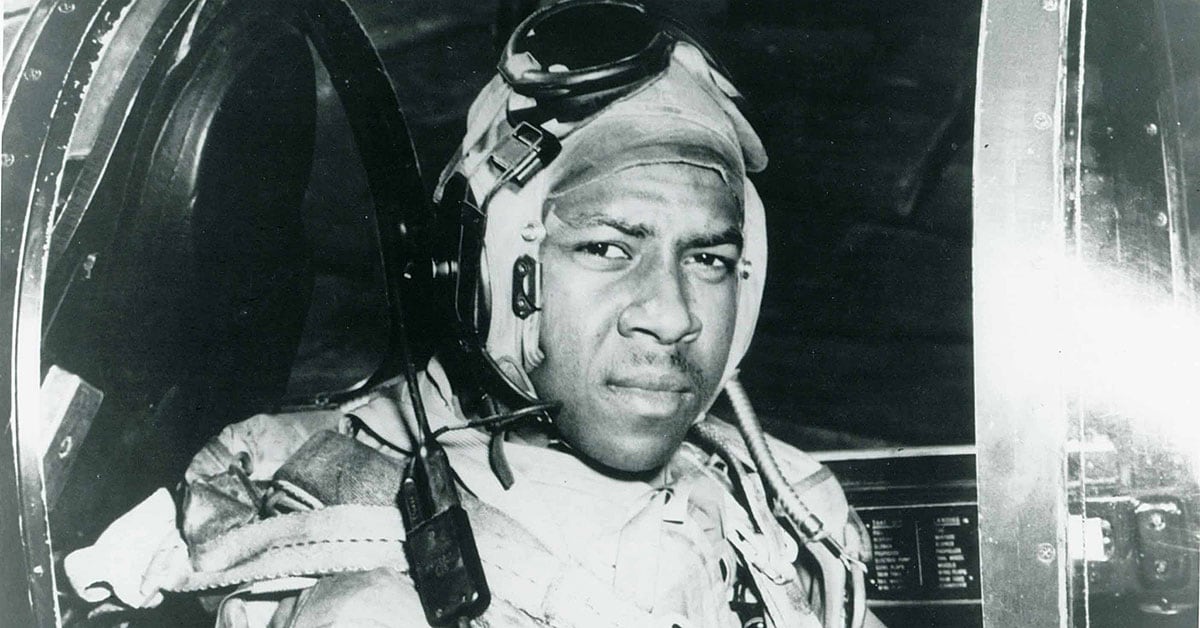

Tom Hudner’s story is also Jesse Brown’s story. It’s our country’s story, too. It belongs to the America of our ideals, of our better angels.

Hudner grew up in privilege in Massachusetts, where his father owned a chain of grocery stores. Brown grew up in Mississippi, the son of an African-American sharecropper who possessed very little. Yet these two men became brothers in arms and comrades.

Their story begins in 1949. Soon after Hudner checked into his Navy Corsair fighter squadron, VF-32, his flight leader took him aside and said, “We’ve got a Negro pilot in ’32. First in the Navy. Will you be OK taking orders from a Negro?”

The question was a weighty one. President Truman had desegregated the military the year before. The Civil Rights Act was about 15 years away. Many Americans didn’t think white and black soldiers would fight for each other. Some used this cynical assumption to oppose desegregation. The country’s not ready, they said.

Hudner looked at his commander and said, “At my high school we only had one colored kid and I was friends with him.”

On Dec. 4, 1950, during the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir, Brown and Hudner were on a “roadrunner” mission when Brown’s plane was hit by small arms-fire. He immediately lost oil pressure, and his engine seized. Too low to bail out, Brown had to make a crash landing on a snow-covered mountainside north of the Chosin.

Hudner, loitering overhead, looked down at the rising smoke and saw Brown’s canopy slide open. Then the downed pilot waved his arms, but he didn’t get out of the aircraft.

Hudner decided he had to act. He disregarded instructions and deliberately crash-landed his own plane to try to save his squadron-mate.

RELATED

But Brown’s legs were pinned, and Hudner couldn’t free them. When the rescue helicopter arrived, men tried to get him out with an ax and anything else they could find. But they couldn’t. Darkness was coming, and so, presumably, were Chinese troops. They had no choice but to leave Jesse Brown in his airplane, where he perished.

Hudner’s actions could have gotten him court-martialed. He and his fellow pilots had been specifically told not to do what Hudner did if one of their squadron-mates went down.

The Norfolk Journal and Guide, a black newspaper, called Hudner’s heroic attempt to save Brown “a lesson in the brotherhood of man.”

I don’t find Hudner’s actions that day as remarkable as his actions prior to those heroics. Before they deployed, members of the squadron went to a bar in San Diego. As soon as the waiter announced that he wouldn’t serve Jesse Brown, Hudner led the pilots on standing up and walking out. He was in disbelief — the man can fight for his country, but he can’t order a drink?

I met Tom Hudner in 2004 when he spoke to my Marine Corps flying squadron. He regaled us with stories of flying the Corsair and told us about Jesse Brown. Of his attempt to save his friend, he said, “Jesse would have done the same thing for me.”

We asked him about Daisy, Brown’s widow, and Pam, the baby daughter he left behind. Hudner talked about them like they were his own family. But he didn’t mention that when he came home from Korea, he had ensured that they were taken care of financially.

Over the 67 years of his life after that fateful day, Hudner honorably carried the burden of being in that unique class: Medal of Honor recipient. He served another 23 years in the Navy, retiring in 1973 at the rank of captain. He fought for his country, both in and out of uniform.

He wasn’t a protester or a politician. He was a naval officer and a veteran who used his voice and his platform as a war hero to advocate for others. He lived his values and left his country a bit better than he found it.

What could be more patriotic than encouraging your country and your fellow citizens to be their best selves?

Scott Cooper is a retired Marine Corps lieutenant colonel who flew the EA-6B Prowler and made multiple war-zone deployments, including five to Iraq. He’s the founder of Veterans for American Ideals, a project of Human Rights First.