WASHINGTON — When confirmation hearings for the next Veterans Affairs secretary begin in a few weeks, privatization of the department will be the main focus of most lawmakers’ questions.

Nearly everyone in the veterans community and on Capitol Hill is against privatizing VA — and nearly everyone has a different definition of what privatization is.

Last week, VA officials released a statement titled “Debunking the VA Privatization Myth,” which insists “there is no effort underway to privatize VA,” and “to suggest otherwise is completely false and a red herring designed to distract and avoid honest debate on the real issues surrounding veterans’ health care.”

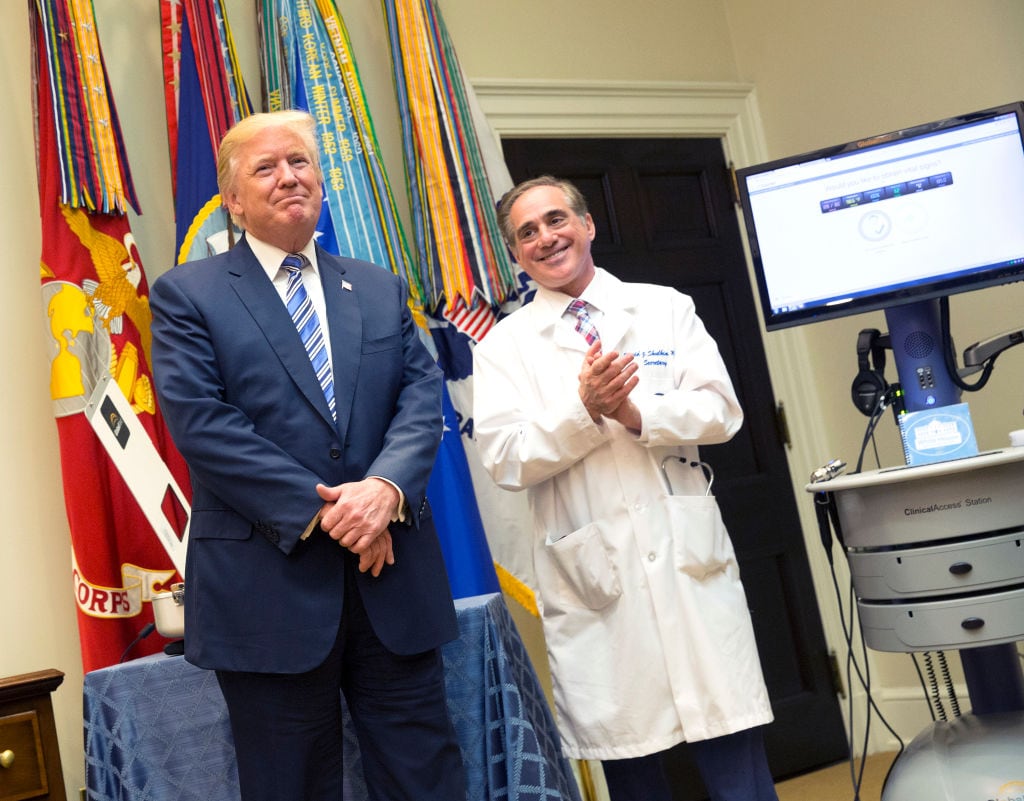

The move came in response to comments from former VA Secretary David Shulkin, fired by President Donald Trump over Twitter less than two weeks ago.

In an op-ed just hours after his dismissal, Shulkin warned of individuals within the White House who “seek to privatize veteran health care as an alternative to government-run VA care.”

But the definition of what privatizing the nearly $200 billion department would mean depends largely on who is making the argument.

RELATED

The VA “debunking” statement notes that the department budget has gone up five times in the last 20 years, and the VA workforce has increased about 60 percent since then (to around 385,000 workers). The argument is that adding more resources to the bureaucracy can’t be considered privatizing VA.

But veterans groups have noted that increase is a function of inflation and increased demands on the department, and has little to do with future plans to shift more resources into community care programs in lieu of building up more VA infrastructure.

Shulkin warned in his piece against “dismantling of the department’s extensive health care system,” but he also supported closing down a number of aging VA facilities and increasing partnerships with private-sector physicians to improve veterans’ access to medical appointments.

Meanwhile, both Democrats and Republicans on Capitol Hill have vowed to oppose “privatization” of VA even as they near an agreement that could substantially increase the number of outside care appointments for veterans, something that multiple lawmakers just a few years ago said amounted to outsourcing VA responsibilities.

“The folks who actually want to privatize VA won’t use the word, because they know it’s a political fight,” said Paul Rieckhoff, executive director at Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America. “But there’s no doubt it is already happening.”

Moving veterans outside VA

During the 2016 presidential campaign, then-Republican candidate Ben Carson suggested eliminating VA medical programs in favor of health care vouchers that veterans could take anywhere in the country.

By nearly any advocate’s definition, that idea amounts to fully privatizing VA.

The plan has been floated several times over the years, but it has failed to gain serious traction because of the dramatic effects it would have on existing care programs.

About $72 billion of VA’s budget this fiscal year goes to medical care, and the department has more than 1,200 medical facilities nationwide.

With Carson’s model as the extreme edge of the debate, the privatization fight largely hinges on how much medical care should go outside the department’s existing infrastructure, and what counts as too much reliance on the private sector.

Last year, VA administrators coordinated more than 60 million medical appointments for veterans. More than one-third of them were with doctors and offices outside the Veterans Health Administration, either because the department didn’t offer the right services or officials felt veterans would be better cared for through outside options.

Critics of the administration have warned that increasing the percentage of appointments — and money — heading out of VA and into the private sector could weaken department services.

“Each time you’re taking resources out and putting them into the private sector, you’re leaving VA dying on the vine,” said Will Fischer, director of government relations for VoteVets.org. “It’s bit by bit draining of VA.”

For Fischer’s group — which has ties to the Democratic Party and has attacked Trump on a host of national security issues — the department is already on a dangerously close path to privatization, with plans to bump up community care programs to more than $14 billion in fiscal 2019.

Rieckhoff said he defines privatization as “any dollar spent by the government on government programs that goes to the private sector instead.”

By that definition, large swaths of VA programs have been privatized for years.

“The real fight here is over ‘full privatization’ versus ‘expanded privatization’ at VA,” he said. “But you can’t say you want more private care options in the community through VA but you are totally against privatization. That doesn’t make sense.”

Most of the larger veterans groups have used the charges of privatization to express serious concerns about efforts to boost outside care programs, and pushed to match them with equal funding to ensure that VA medical centers are being improved, not ignored.

“Our view is that Congress and the administration must fix what is wrong with the VA health care system — improve hiring authorities, expand and fix its aging infrastructure, improve access, customer service — and not just simply turn to the private sector when VA facilities are having problems,” said Carlos Fuentes, director of the National Legislative Service at Veterans of Foreign Wars.

“Community care is part of the solution, but not the only answer.”

Privatization vs. Choice

One of the more recent proposals that alarmed some vets groups was a proposal by Rep. Doug Lamborn, R-Colo., that would create a veterans health insurance program to allow participants to skip the department procedures entirely and get private-sector medical care at taxpayers’ expense.

When it was introduced last fall, VFW officials blasted the idea as an effort to “kill the VA as a provider of care to America’s veterans” and labeled it a blatant “privatization attempt” by the congressman.

He bristled at the accusation.

“Our veterans deserve the highest degree of care,” he said in a statement. “Giving them options to choose their healthcare plans and doctors is empowering.”

The plan closely tracks with one previously backed by Concerned Veterans for America, which has close ties to the conservative Koch brothers’ network and the Trump administration.

In 2015, the group issued a report calling for converting the Veterans Health Administration into a government-chartered nonprofit and having it compete against private-sector companies for federal funding.

Veterans groups have said that amounts to privatizing VA responsibilities. CVA officials say that’s ridiculous.

Dan Caldwell, executive director at CVA, said selling off VA facilities or completely defunding the department would equal privatization.

But “the misrepresentation of efforts to expand veteran health care choice as ‘privatization’ is simply an attempt to undermine popular and common sense concepts which have overwhelming support among veterans.”

Slowly siphoning resources

Many of the privatization fights surrounding VA trace back to 2014, in the wake of the wait-time scandal that forced the resignation of then-Secretary Eric Shinseki.

In an effort to get veterans quicker access to medical appointments, Congress approved (by an overwhelmingly bipartisan majority) a new VA Choice program that allowed veterans who faced long waits for department care or long travels to department hospitals to instead pay for medical treatments in their community with public dollars.

The idea drew criticism from some liberal groups, who warned the three-year program would slowly siphon off resources from the federal health system and that money would be better spent hiring more VA physicians and improving existing VA hospitals.

Since then, VA officials under Trump and former President Barack Obama have pushed for more simplification and flexibility on a range of community care programs, including Choice. Lawmakers removed the program’s end date last summer and added more than $4 billion to the program’s original $10 billion funding cost.

That has intensified the privatization accusations.

“Once you start cannibalizing VA infrastructure, you are on your way to privatization,” said Lou Celli, national veterans affairs director for The American Legion.

He and other veterans groups worry that critics of the VA system will look at reduced numbers of patients at department hospitals as reasons to slash funding and staff, creating a death spiral for the system.

“The word ‘choice’ has become a dog whistle for urging veterans to seek care outside of the VA,” said Sherman Gillums Jr., AMVETS’ chief strategy officer. “The demand for healthcare would then become profitable for corporations and organizations that provide healthcare, essentially commoditizing veterans healthcare, with no competition from a government system.”

Advocates note that outside doctors don’t have expertise in identifying service-connected injuries like burn pit exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Maintaining an effective system of the things VA does best is a must,” said Carl Blake, executive director at Paralyzed Veterans of America. “It’s specialized services like spinal cord injury care, polytrauma, amputee and mental health. Those services don’t exist in a vacuum and are at risk when the system shrinks to support the greater cost in the community.”

The looming VA fights

Trump’s VA has pushed back on the idea that shifting more care outside the VA equals privatization of core department missions, even though the president just two months after the election said he would consider privatizing some parts of the department if it means better care for veterans.

Leaders in the House and Senate for months have been working on a VA health care overhaul package that would broaden eligibility for private-sector veterans care even more than the existing Choice program.

Veterans who previously didn’t meet travel criteria could appeal based on the quality of services rendered in their community, or even opt for two walk-in appointments with private-sector doctors at taxpayers expense without any prior approval from VA administrators.

But the Republican-authored plan, which was nearly passed as part of the budget omnibus package last month, also keeps most aspects of veterans health care under VA control, giving department officials the right to deny outside care in some cases.

Senate Democrats have given support for the measure, even though it likely will mean increasing the number of appointments paid for outside VA. House Democrats have expressed reservations in recent negotiations, with some voicing concerns that it amounts to privatization.

White House officials have argued department managers should have as little role as possible, possibly even none at all, in deciding what doctor a veteran can visit. Shulkin and mainstream veterans groups have argued that VA cannot be completely divorced from patients’ care without dangerous health consequences.

Whether the proposal can move through Congress while lawmakers are considering the new VA secretary nominee is unclear.

But regardless, that nominee — White House physician Ronny Jackson — is expected to face a slew of questions on those “privatization” issues during his meetings with lawmakers in coming weeks, and during his confirmation hearing.

In a statement, House Veterans’ Affairs Committee ranking member Tim Walz, D-Minn., said that he wants to make sure Trump’s new pick to lead VA is ready to “put veterans first, listen to [veterans service organizations], and fight any and all attempts to fully privatize the VA.”

Sen. Tammy Duckworth, D-Ill. and herself a wounded Iraq War veteran, has already warned that she believes the Trump administration “wants to push VA down the dangerous path of privatization.”

Administration officials say that simply isn’t true.

“The fact is that demand for veterans’ health care is outpacing VA’s ability to supply it wholly in-house,” VA’s statement said. “And with America facing a looming doctor shortage, VA has to be able to share health care resources with the private sector through an effective community care program.

“There is just no other option.”

Leo covers Congress, Veterans Affairs and the White House for Military Times. He has covered Washington, D.C. since 2004, focusing on military personnel and veterans policies. His work has earned numerous honors, including a 2009 Polk award, a 2010 National Headliner Award, the IAVA Leadership in Journalism award and the VFW News Media award.